Educate

What We Did to Raise Awareness of Procurement Issues and Exchange Information

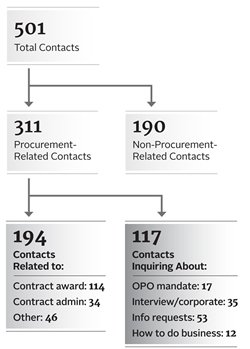

Image description

This diagram identifies the number of total contacts received by the Office of the Procurement Ombudsman in the 2013-14 fiscal year as 501. This total number is then broken down below into procurement-related contacts (311) and non-procurement-related contacts (190). Of the 311 Procurement-related contacts, 194 are identified as related to contract award (114), contract administration (34) and other (46). The remaining 117 are described as contacts inquiring about OPO mandate (;17), interview/corporate (35), information requests (53) and how to do business (12).

Communication is a critical component of the Educate pillar. Our ability to raise awareness of procurement issues is as linked to our ability to listen as it is to inform.

The 311 procurement-related contacts represent suppliers or government officials who turn to OPO for information and answers. Of these contacts, 117 (38%) fell into the "General Inquiries" category and include such things as questions about our legislated mandate or requests for procurement information. A good many of these inquiries are also from firms looking for information to better understand the various procurement tools and processes used by the federal government. These inquiries suggest an ongoing challenge in providing potential suppliers with clear, plain language instructions on how to do business with the federal government.

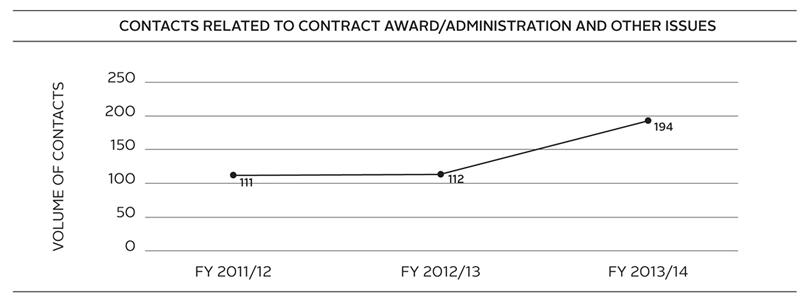

In other instances, suppliers want to discuss or alert us to something more particular or complex. As illustrated in Diagram 3 (on page 18), the Office saw a 73% increase in contacts of this nature, from 112 in 2012–13 to 194 in 2013–14. Of these 194 contacts, 114 (59%) raised issues related to the award of a contract and 34 (18%) spoke to us about issues related to the administration of a contract. The other 46 either provided their views regarding some aspect of procurement or provided suggestions regarding topics the Office should consider examining. As a firm contacting the Office typically raises more than one concern with us, these 194 contacts actually represent several hundred issues. For example, it is not unusual for a supplier to contact us concerned about a failed bid and, in the process, raise other issues such as the department's chosen procurement strategy, the contents of the statement of work or perhaps the department's refusal to provide an explanation of the bid's shortcomings.

Diagram 3

Image description

This diagram illustrates a three year comparative in the number of contacts related to contract award, administration and other issues. The three years are illustrated from left (2011-12) to right (2013-14). In the 2011-12 fiscal year, there were 111; in 2012-13, there were 112; and in 2013-14, there were 194.

Departments and agencies are often best placed to address a supplier's concern. Accordingly, the Office's standard procedure when dealing with suppliers contacting us is to ask whether the implicated department or agency has been given the opportunity to address their concerns. In situations where the department has not been given this opportunity, suppliers are encouraged to contact the department. The Office intervenes once the supplier notifies us that it has unsuccessfully attempted to resolve the concern with the department (which is most often the case), or the supplier is reluctant to contact the department.

Consistent with previous years, the issues most commonly raised to us by suppliers are typically spurred by an unsuccessful bid, a supplier's inability to bid and/or a department's treatment of the unsuccessful supplier. The list of the most common issues registered with the Office illustrated in Diagram 4 fall into these categories.

Diagram 4

Most Common Procurement-Related Issues 2013–14

- Evaluation and Selection Plan (e.g., bias for or against supplier/class of suppliers, vague or unclear, excessive criteria, unbalanced weighting)

- Evaluation of Bids (e.g., undisclosed/changed criteria, inconsistent application of criteria)

- Procurement Strategy (e.g., competitive vs. non-competitive, type of contracting vehicle)

- Professionalism (e.g., unreturned phone calls, unprofessional treatment, inconsistent advice, employer-employee relationship)

- Debriefing (e.g., refused to provide, or provided insufficient information)

- Statement of Work or Specification (e.g., bias for or against individual/class of suppliers, vague or unclear, insufficient information)

While the issues contained in the list have remained consistent over time, this year the Office has noted an increase in the number of suppliers raising concerns regarding how a department has treated them. For example, suppliers have called us to discuss a department's refusal to provide information or not providing sufficient information, not returning phone calls, or staff behaving unprofessionally or providing inconsistent advice.

Hearing about concerns and issues is key to the Office's ability to identify potential shortcomings or areas for improvement in the federal procurement system. As such, in 2013–14 several new initiatives were launched as part of the Office's educate pillar. These included the following:

- 15 town hall style meetings with Canadian businesses from across the country. We discussed our legislated mandate and services, and in turn, participants shared their experiences and suggestions for doing business with the federal government.

- A social media presence with the creation of Twitter accounts (@OPO_Canada and @BOA_Canada).

- An online forum, "Share your thoughts on federal procurement", enabling Canadians to share either anonymous or identified feedback through the OPO website, which led to an additional 40 contacts to the Office.

- A quarterly e-newsletter, "Perspectives", raising awareness of OPO's mandate and services and highlighting upcoming OPO events, recent publications and initiatives.

These initiatives, coupled with the Office's traditional avenues, enabled suppliers to express their views, opinions and concerns. Highlights of some of the feedback received as a result of these initiatives include the following:

- Limited opportunities for the participation of small and medium-sized businesses (SME) in large federal procurement projects.

- The negative impact on regional suppliers of bundling (i.e., grouping of commodities) and solicitations which require the ability to deliver on a national scale (e.g., National Master Standing Offers).

- Departmental reluctance to use directed or sole-source contracting for requirements under the $25,000 threshold for competition.

- Excessive use by departments of directed or sole-source contracting for requirements under $25,000.

- The amount of paperwork and time required to respond to solicitations reduces the profit margins and in certain cases makes it not worth bidding.

- The burden of being required to purchase liability insurance in low-risk contracting.

- The lack of up-front procurement planning by departments and subsequent negative consequences on suppliers (e.g., delays resulting in requests for suppliers to meet unreasonable delivery times, changing requirements mid-stream, cancelling the procurement process after suppliers have invested significant time and effort in bidding).

- The difficulty of building relationships and communicating with departments as procurement personnel are too focused on the process.

- The complexity and time associated with the security clearance process which is causing suppliers to miss out on business opportunities.

In addition, there were a few issues which were raised by both suppliers and government officials.

Examples include:

- The lack of procurement training and experience of some government personnel.

- The monitoring of vendor (i.e., supplier) performance.

These initiatives have allowed us to listen, learn and, where required, provide explanations to address the issues raised. In other cases, the provision of information was not enough and we were called upon to help facilitate the resolution of issues.

- Date modified: