Part II: 2010-2011 Results

Following the retirement of the inaugural ombudsman, the Office was without an ombudsman for approximately six months. During this period, the Regulations did not allow for the delegation of authority permitting new procurement practices reviews and investigations to be launched and reports released. Despite the absence of an ombudsman, the Office's daily business continued under the direction of the Deputy Procurement Ombudsman. In keeping with the business model that provides for a collegial and cooperative approach, complaints were addressed in an unbiased, timely and independent manner.

The following section provides details on OPO activities.

INQUIRIES AND COMPLAINTS

The Office was developed on a "service first" business model and is committed to offering prompt, personalized and seamless service to federal procurement stakeholders.

Our approach in fielding procurement-related complaints is prescribed by the Regulations, which provide the parameters for our activities. To ensure adherence to our legislated mandate and the Regulations, each procurement complaint is received in writing and assessed by a team of federal procurement experts and a senior commercial legal advisor. The assessments and any associated recommendations are provided to the Ombudsman for consideration and to determine whether the complaint will be reviewed. As prescribed by the Regulations, the Ombudsman is required to make a determination within 10 working days of receipt of the complaint (referred to below as the determination period).

To ensure adherence to our legislated mandate and the Regulations, each procurement complaint is received in writing and assessed by a team of federal procurement experts and a senior commercial legal advisor.

TESTIMONIAL… TESTIMONIAL 1

A Request for Proposals clarification request went unanswered for three weeks. Once it was answered, the supplier asked for an extension of the bid closing period. The request was denied, so the supplier contacted the Office concerninginadequate time to prepare the proposal. Through the Office's intervention, it was determined that the questions and answers were improperly posted on MERX™. As a result, the department agreed to an extension. The supplier wrote:

"Thank you very much. I do appreciate the prompt response from the Ombudsman Office. I am pleased with the extension and withdraw my formal complaint."

Specifically, complaints from a supplier regarding the award of a contract are assessed using the following prescribed criteria:

- the Complainant must be a Canadian supplier;

- the complaint must be filed in writing;

- the complaint may only be filed after the award of the contract to which the complaint relates;

- the contract in question must be under $25,000 for goods or under $100,000 for services;

- the complaint must be filed within the prescribed timelines (within 30 working days after the award of the contract became known or should have reasonably became known to the Complainant—under certain circumstances and at the Ombudsman's discretion, this period may be extended up to 90 working days);

- the department to which the complaint relates must be under the jurisdiction of the Ombudsman;

- the contract whose award is the subject of the complaint is not covered by any of the exemptions or exceptions as defined by section 2 of the AIT, including those made under articles 1802 to 1806;

- the facts and grounds on which the complaint are based are not and have not been the subject of an inquiry before the Canadian International Trade Tribunal or a proceeding in a court of competent jurisdiction;

- the requirements set out in subsection 22.2(1) of the Act and section 7 of the Regulations have been met; and

- there are reasonable grounds to believe that the contract was not awarded in accordance with the Financial Administration Act.

An investigation will be undertaken if a supplier meets the requirements prescribed by the regulations and the complaint raises, for example:

- discriminatory or restrictive evaluation criteria

- the directed award of a contract

- the award of a contract resulting from an unfair advantage

- the application of undisclosed evaluation criteria

Complaints from a supplier regarding the administration of a contract must also meet some of the above criteria; however, no dollar thresholds apply. In addition, contract administration complaints are assessed against the following regulatory prescribed criteria:

- the Complainant must have been awarded the contract to which the complaint relates; and

- the complaint does not involve the scope of work or the application or interpretation of a contract's terms or conditions.

As with complaints regarding awards and administration, if the Ombudsman determines that the complaint meets the criteria as prescribed by the Regulations and merits review, the Ombudsman is required to notify the Complainant and the affected department of the decision and provide that department with a copy of the complaint for a response. During the determination period (10 working days) and with the Complainant's written permission, the Office will:

- contact the relevant department to flag the concern and gain insight into its perspective;

- attempt to facilitate a resolution within the determination period; and

- if the facilitation process is unsatisfactory and does not result in the withdrawal of the complaint or the cancellation of the award of the contract in question, initiate an investigation as prescribed by the Regulations.

The Office will produce a report within 120 working days, which will include findings and/or any recommendations to the Minister of the affected department, the Minister of PWGSC and the Complainant.

If the complaint does not meet the criteria prescribed by the Regulations, the Office may:

- with the supplier's permission, contact the department to attempt to address the concern;

- provide alternate contact information, assistance and options for consideration; and

- with the supplier's permission, refer the concern to the appropriate deputy head for any necessary action.

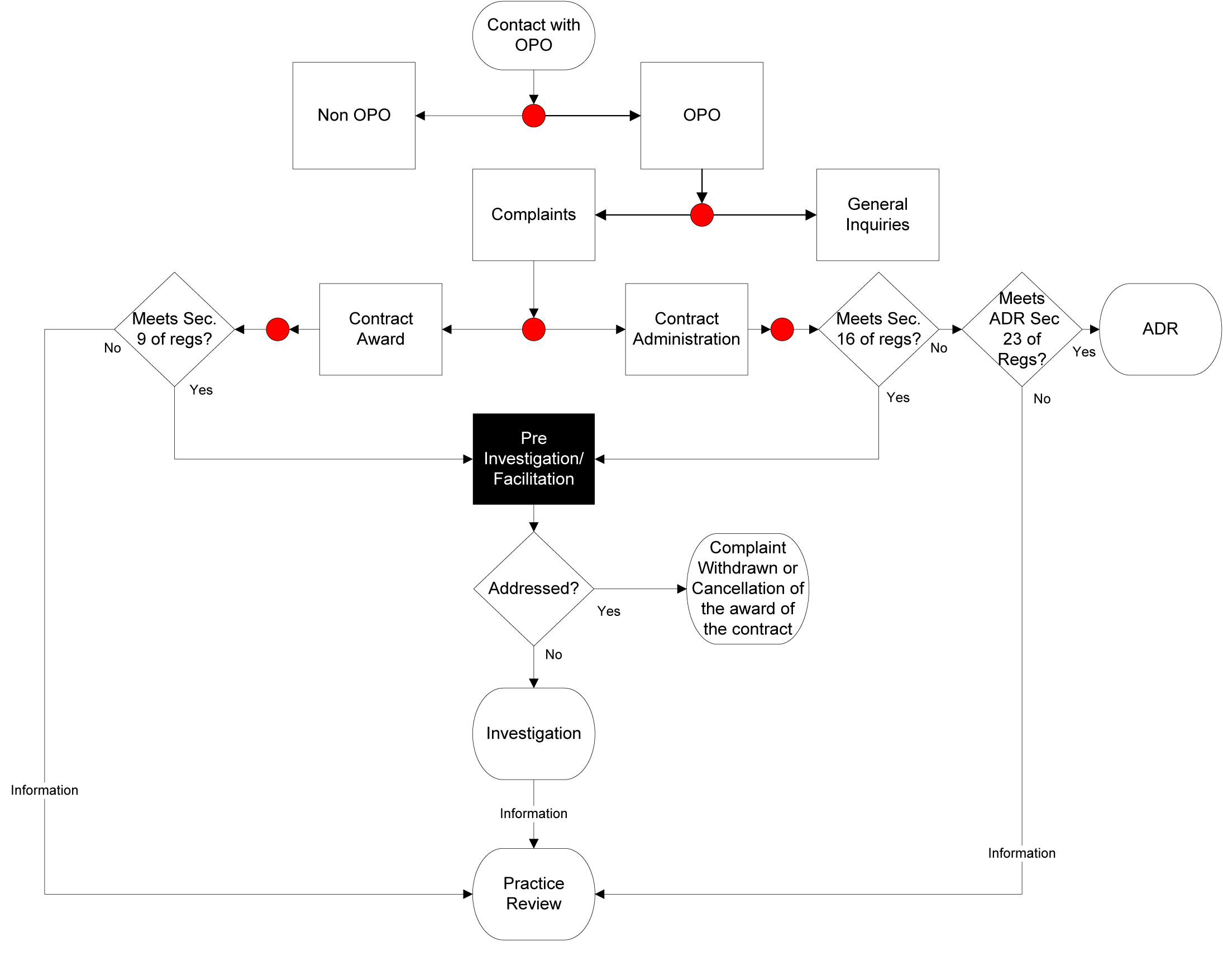

Although the Regulations may be considered prescriptive, the Office has the discretion to act informally when facilitating procurement-related issues. Within the established process, as illustrated in Diagram I, the team of procurement investigators may suggest other courses of action for consideration, including encouraging departments to actively participate in addressing supplier concerns through dialogue and providing suppliers with information and assistance to increase their knowledge and understanding of the Government of Canada's procurement processes.

TESTIMONIAL… TESTIMONIAL 2

The Office was contacted by a firm interested in supplying the federal government and seeking to find information on how to do busi ness with the federal government. The information relayed by another organization was unclear, so the firm turned to the Office to clarify and demystify the process. The relieved supplier stated:

"I just wanted to let you know that (the investigator) has been extremely helpful. Her professionalism andkindness is something we do not see very often these days when dealing with the government and it was refreshing to witness it. Thank you for your help and that of your team."

Diagram I

Procurement Inquiries and Investigations Process Map

The Office is engaged in facilitating disputes amongst procurement stakeholders and is committed to proactively finding solutions before issues escalate. This early intervention helps to avoid long and costly disputes where business relationships are negatively impacted. Through our work with departments to proactively address supplier complaints and concerns, all parties benefit.

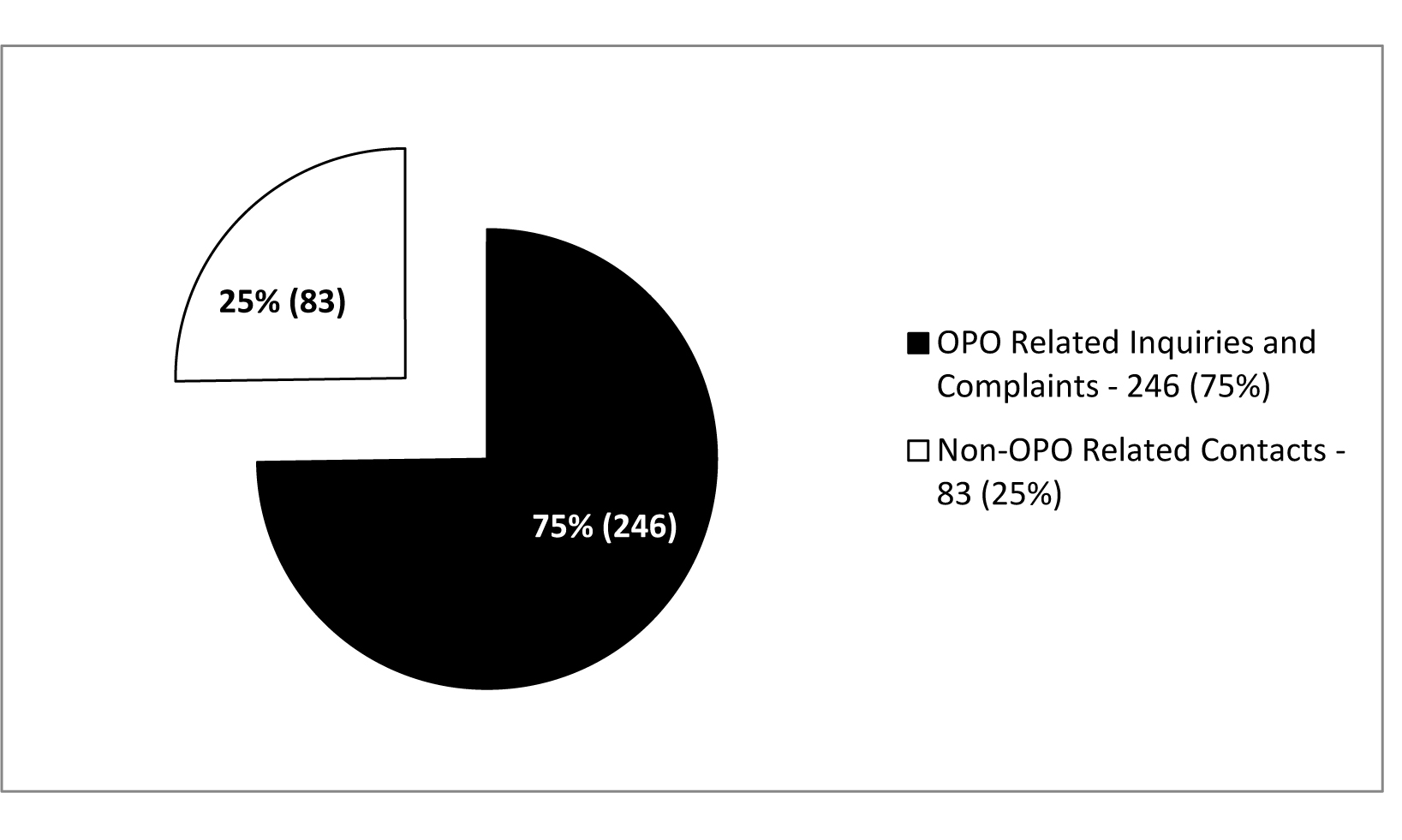

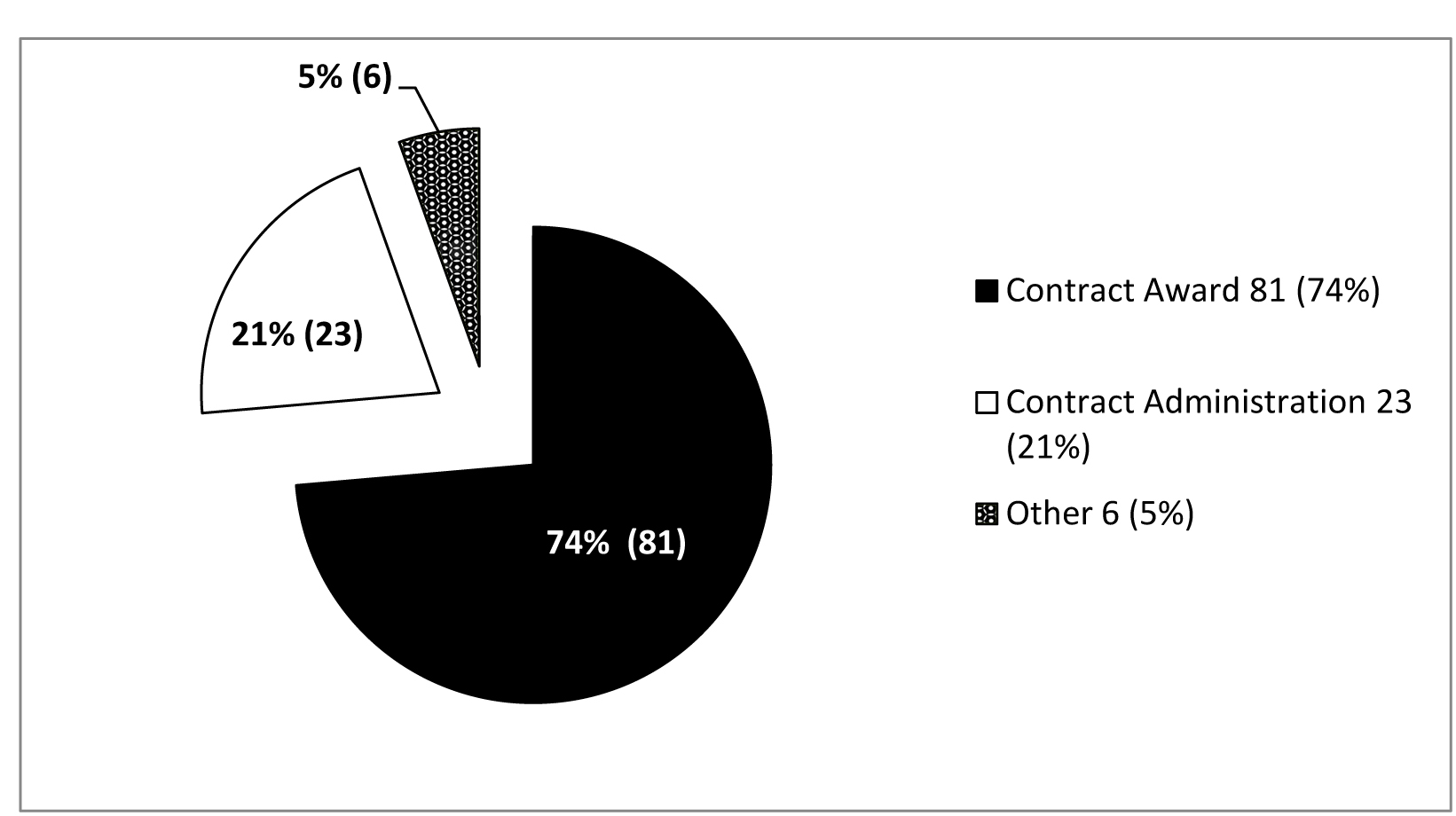

During the last fiscal year (2010-2011), the Office was contacted 329 times. As illustrated in Diagram II, roughly 75% (246) of these contacts were inquiries or complaints involving some aspect of procurement, of which 45% (110) were actual complaints. Diagram III shows that 74% (81) of these complaints pertained to contract award while 21% (23) regarded contract administration.

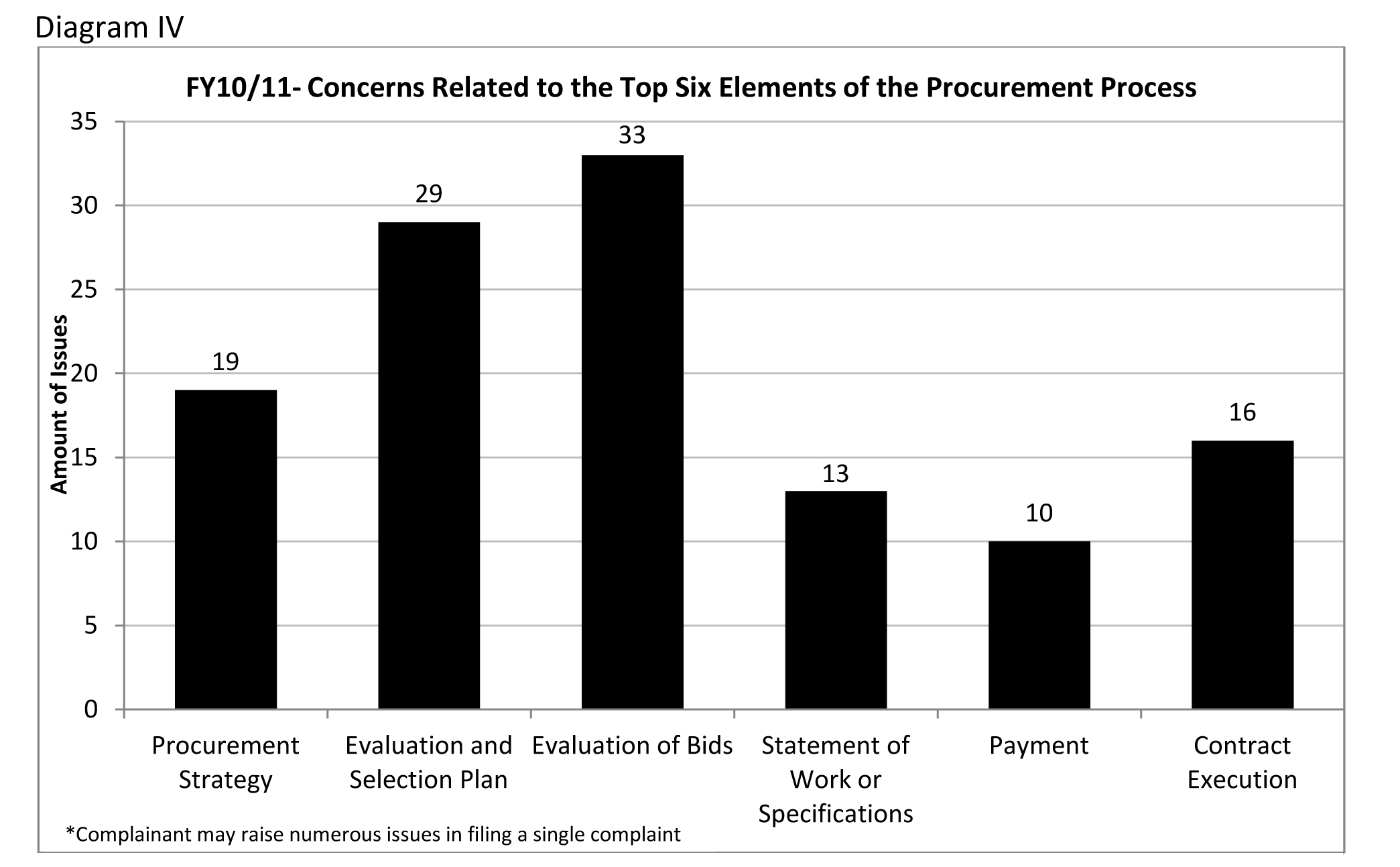

Diagram IV provides an indication of the most common areas of concern (regarding both contract award and administration) for suppliers.

The primary areas of concern raised by suppliers regarding the award of contracts related to:

- the evaluation of bids (e.g. an unfair evaluation process)

- the evaluation and selection plan themselves (e.g. restrictive mandatory criteria or a biased rating scheme)

- the procurement strategy (e.g. too often non-competitive)

- the statement of work (e.g. unclear or favouring a specific bidder)

With regard to the administration of contracts, the following are the primary areas of concern raised by suppliers:

- payment issues (e.g. late payments)

- contract execution (e.g. requesting extras or altering the contract)

Diagram II

2010-2011: Volume of Contacts – 329

Diagram III

2010-2011: 110 Complaints Breakdown

Diagram IV

2010-2011: Concerns Related to the Top Six Elements of the Procurement Process

The Office receives inquiries from stakeholders looking for information to better understand the various procurement tools and processes used by the federal government. The contacts suggest that suppliers need to be provided with accessible and clear instructions on how to do business with the federal government. The volume of calls the Office receives suggests that federal organizations need to better educate potential suppliers to enable them to submit responsive proposals for inclusion in procurement vehicles such as standing offers and supply arrangements.

Suppliers have also advised the Office of confusion regarding the bidding process on government solicitations. Suppliers appear to be having difficulties understanding solicitation documents and therefore have problems submitting compliant proposals. For example, the Office hears of suppliers encountering unclear or contradictory solicitation terms and conditions and varied procurement processes for similar acquisitions by different federal organizations. Finally, suppliers often express frustration with obtaining information or clarification from government procurement officials.

The volume of calls the Office receives suggests that federal organizations need to better educate potential suppliers to enable them to submit responsive proposals for inclusion in procurement vehicles such as standing offers and supply arrangements.

INVESTIGATIONS

Despite our best efforts to alleviate concerns that come to our attention, in the past fiscal year three investigations were launched and one that commenced in 2009 was withdrawn by the Complainant. Accordingly, the Office released three investigative reports. Each report concerned complaints about the award of a contract, as follows:

- A complaint was received concerning the award of a contract for services. The Complainant alleged that the process was unfair and believed that an inappropriate relationship existed between the Department and winning bidder and that a conflict of interest existed. The Office's investigation did not provide evidence to substantiate the allegations. However, the Office concluded that the situation raised the "perception" of conflict of interest or the possibility of unfair advantage. The investigation also revealed that some of the evaluation criteria were subjective, that the procurement strategy lacked precision and that there was inadequate documentation to support the evaluation. The Office's recommendations resulted in the Department's decision to terminate its arrangement with the bidder and to take corrective action to improve its procurement practices.

-

A complaint was lodged regarding mandatory criteria, which the Complainant alleged limited the openness of the solicitation process on the basis that it was restrictive and discriminatory.

The Complainant attempted to address these concerns with the Department, but was not satisfied with the response. The Office's investigation found that the mandatory criteria did not prevent the Complainant from bidding on the requirement. However, the Department agreed to take action by undertaking further analysis.

- A Complainant contended that a Department did not award a contract to the lowest bidder, as set out in the Request for Proposals (RFP). It was further alleged that contradictory wording in the RFP led to a wrongful disqualification of the Complainant's bid. The Office's investigation concluded that the wording was unclear and potentially led to conflicting interpretations. Since a condition in the Complainant's proposal resulting from the RFP had rendered their bid non-compliant, it was recommended that the Department improve the identified shortcomings in future RFP processes.

- An investigation that commenced in the 2009-10 fiscal year was withdrawn by the Complainant. For a variety of reasons, including the time taken by the Office to process the file and additional delays related to a perceived conflict of interest, the Complainant withdrew the complaint out of frustration.

In addition to the above-mentioned cases, two investigations are currently underway.

TESTIMONIAL… TESTIMONIAL 3

A complaint was prompted when, after weeks of waiting for a quote from the Complainant on a "right of first refusal" standing offer, the procurement authority went to the next supplier on the list. The Complainant stressed that since the procurement authority had not given a response deadline, it should have waited for the Complainant's response. Through facilitation, both the supplier and the procurement authority learned that providing a deadline for bids must be included in solicitations to avoid confusion and misunderstanding. The procurement official wrote:

"I have not had any issues until I received this complaint and take pride in transparency. I understand your point pertaining to time sensitivity, and on all future requests I will be including a timeline for responses."

TESTIMONIAL… TESTIMONIAL 4

"I just wanted to write you a quick note to let you know how impressed I was with the service provided by your organization. As you know from the documentation the file in question has been bouncing around at great cost… As a small business it is quite intimidating to have Her Majesty say "pay up or go tocollections, " particularly when we feel adamant the company acted in good faith and did nothing wrong…

Your intervention I think has saved the Crown untold salary dollarsdealing with the issue and produced a balanced result based on the facts of the situation. For that we thank you. I wish we had been aware of the service earlier."

ALTERNATIVE DISPUTE RESOLUTION

The Regulations stipulate that the Ombudsman will ensure the provision of an Alternate Dispute Resolution (ADR) process. Either party to a contract can request an ADR process; however, both parties must voluntarily agree to participate. The purpose of an ADR process is to create an unbiased environment in which the parties can reach an amicable settlement to their dispute without resorting to an often lengthy and expensive judicial review.

When parties agree to an ADR process regarding the interpretation or application of a contract's terms and conditions, the Office provides independent ADR services. The ADR process is confidential and any resulting settlement or agreement is considered confidential and legally binding between the parties.

In past years, the Office has provided parties to a conflict with three options: facilitation; mediation; and neutral evaluation. The Office is in the process of undertaking a feasibility study to determine potential future options. In the interim, the Office has ensured that facilitation capabilities are available internally, with minimal to no charge to the parties.

As prescribed in the Regulations, within 10 working days of receiving an ADR request, the Ombudsman shall ask the other party (or parties) to agree to participate. In keeping with its business model, the Office attempts to address concerns within this 10-day period by encouraging dialogue. Should a party decline to participate, the Ombudsman is required to notify the requesting party that their ADR request cannot be granted.

In the 2010-2011 fiscal year, the Office received ten ADR requests.

- Two did not meet the requirements under the Regulations, as they were not filed by parties to the contracts in dispute.

- Of the remaining eight that did meet the regulatory criteria:

- four were declined by the federal department involved;

- three were resolved to the satisfaction of the parties using facilitation; and

- one is ongoing.

In all cases, at issue was the application or interpretation of a contract's terms or conditions.

Responding to inquiries and facilitating disputes also allows the Office to identify systemic concerns within the federal procurement system for further review and study.

ALTERNATIVE DISPUTE RESOLUTION SERVICE

Facilitation: an opportunity for parties to come together in an unbiased setting to discuss their perspectives and participate in open dialogue concerning a contractual dispute, in the hope of coming to a mutually satisfactory agreement.

PROCUREMENT PRACTICES REVIEWS

The Office reviews federal departments' and agencies' procurement practices to assess their fairness, openness and transparency and recommend improvements and best practices. In conducting these reviews, the Office maintains independence from the departments and agencies it reviews.

Although reviews generally follow the same type of process as performance audits, the Office uses a systematic, evidence-based approach in carrying out its work. The Office examines past and current practices and takes into consideration the observations or findings of previous audits or assessments. The reviews are based on the Office's business model of collegiality and cooperation and seek to highlight good practices and identify areas for improvement. The review reports are based on indicative evidence in order to obtain a reasonable level of assurance.

Although reviews generally follow the same type of process as performance audits, the Office uses a systematic, evidence-based approach in carrying out its work.

In the 2010-2011 fiscal year, the Office launched four Procurement Practices Reviews (PPR). With the arrival of the new Ombudsman, the decision was made to move from an annual publishing of all practices review reports to the staggering of reports throughout the fiscal year. This change was introduced in order to reduce the workload on impacted departments and more equitably distribute the Office's workload throughout the year. Consequently, the four reviews undertaken in the 2010-2011 fiscal year are currently in various stages of completion, as follows:

- Following the receipt of a complaint from a public organization, the Office is conducting a practices review regarding the award of four contracts for professional services issued as a result of Advanced Contract Award Notices (ACANs).

- The Professional Services Online (PS Online) tool serves a large number of smaller suppliers that are stakeholders of the Office and was therefore identified as a topic for review.

- A follow-up of the recommendations and good practices noted in the 2008-2009 PPRs is underway. The Office asked the 16 departments and agencies that participated in the original reviews to report what changes had been implemented or planned subsequent to the reviews.

- A review of low-dollar value procurement was initiated in certain departments. This review is addressing some of the concerns raised in the Study on Directed Contracts Under $25,000 referred to in the following point.

In addition to the initiation of these four reviews, one study of procurement practices was completed and published in the 2010-2011 fiscal year. The Study on Directed Contracts Under $25,000 published in July 2010 (see insert above—the full study is available at www.opo-boa.gc.ca), was risk-based, and while it did not include recommendations to improve fairness, openness and transparency, it did identify effective practices.

PRACTICES REVIEWS STANDARDS AND PROCEDURES

The Office has developed a Review Standards and Procedures Manual, which sets the benchmarks for the Office's review standards and contains an outline of all the PPR steps, from initial planning to recommendation and follow-up.

This document will be used to develop a guide for federal organizations participating in a review. This guide will give a sense of what to expect from the Office and what is expected from an organization. The aim is to increase the level of trust needed to foster meaningful feedback to the Office.

"DIRECTED CONTRACTS UNDER $25,000—A RISK-BASED STUDY"

The study revealed that, over the last ten years, approximately 90% of all government contracts had values below $25,000 and the majority were directed to a preselected supplier without competition.

The study found shortcomings in the implementation of two key government procurement transparency measures: justifying and documenting decisions; and publicly disclosing information on government contracts over $10,000. Firstly, when procurement decisions are poorly documented, transparency is weakened, as is the fairness and openness associated with directed contracts. Secondly, information on contracts over $10,000 is not consistently reported, consolidated or searchable and does not contain enough detail for suppliers to decide if it is worthwhile to pursue government business.

The federal government has determined that one of the most significant risks associated with procurement is the training and experience of its procurement specialists. In 2006, it introduced a Certification Program for functional procurement specialists. Certification is not mandatory; however, specialists are required to take some basic training courses. There also appears to be a gap in the training of other personnel involved in the process, such as program managers and individuals performing a challenge function in procurement oversight.

Lastly, while the Treasury Board declared the use of standing offers and supply arrangements mandatory in 2005 for 10 commodity groups of commonly purchased goods and services, the study found that in 2008 more than 200,000 out of approximately 370,000 contracts (including amendments) under $25,000 were awarded through contractual means other than a standing offer or supply arrangement.

OUTREACH

The Office continued to inform procurement stakeholders of its mandate and offerings. Four stakeholder groups were the focus of the Office's effort: national procurement associations, industry associations, other ombudsmen offices and federal government departments.

The Office has also attracted international interest from a number of foreign governments and welcomed delegations from Russia, China, Ethiopia and the European Union.

Continuing with the Office's efforts to be accessible and user-friendly to both the supplier community and government departments and agencies, the Office updated its Web presence and supplier complaint form. There were also several articles produced on the Office's operations for procurement magazines.

These outreach efforts have proven to be an effective means of communicating our presence and role. They have also continued to provide the Office with opportunities to understand our stakeholders while informing them of our mandate.

OPERATIONS

To ensure that our work is impartial and conforms to the highest professional standards, the Office developed a values and ethics code (insert below) which also serves to maintain and enhance public confidence in the integrity of the Office. All public servants, consultants, contractors and temporary staff who perform work for the Office are expected to adhere to this Code. The Office is responsible for ensuring that it demonstrates its values, ethics and professional conduct in all its actions and behaviours.

In addition, as part of an ongoing effort to create a work environment conducive to cooperation and collaboration, the Office conducted an employee survey. The results of the survey identified potential improvements in the areas of mobility and communication; however, overall the feedback demonstrated a high level of satisfaction with our work environment and culture.

With the arrival of the new Ombudsman, the Office initiated the development of a strategic plan. The completed plan will set forth the overall vision and mission of the Office and be supported by an operational plan that will, in part, address the results of the employee survey.

THE OFFICE'S CODE OF VALUES, ETHICS AND PROFESSIONAL CONDUCT

The Office acts at all times to protect the public interest and create an atmosphere of trust with colleagues and stakeholders by:

- demonstrating respect, fairness and courtesy;

- performing duties so that confidence and trust in the integrity, objectivity and impartiality of the Office are preserved and enhanced;

- responding in an unbiased, independent and efficient manner;

- being pragmatic and reasonable and demonstrating rigor in all activities;

- continuously aiming to excel in conducting the work of the Office;

- ensuring that the value of transparency in the Office is upheld without compromising the value of confidentiality where it is required by law or circumstance; and

- ensuring that diversity and quality of life are part of the Office culture.

- Date modified: