Section 2 - Getting Down to Work

Practice Reviews

In 2004, in a survey questionnaire reviewing government procurement, the Lastewka Task Force described procurement as follows:

"Procurement" is the process of acquiring goods, services and construction from third parties. The activities involve four phases:

- the pre-contractual phase, which includes activities related to requirement definition and procurement planning;

- the contracting phase, which includes all activities from bid solicitation to contract award;

- the contract administration phase, which includes activities such as issuing contract amendments, monitoring progress, following up on delivery, payment action; and

- the post-contractual phase, which includes file final action (e.g. client satisfaction, contractor agreement to final claim, final contract amendment, completion of financial audits, proof of delivery, return of performance bonds) and close-out (e.g. completeness and accuracy of file documentation and adherence to file presentation standards).

With this definition in mind, our Procurement Practices Review team uses a systematic, evidence-based approach to carry out independent, objective reviews of federal government procurement practices, including the application of procurement policies and the processes, tools and activities related to acquiring goods and services.

"The foundation of government procurement is openness and best value, and everyone should have equal access. If any system or process impedes that, we will speak up about it and if required report it."

– Shahid Minto before the Standing Senate Committee on National Finance, February 2008

Selecting the topics for review is a complex task.

The issues raised by suppliers and government, set out in "What we have heard," constituted our starting point for our first year of full operation. We carried out a scan of issues raised in or by the media, the Canadian International Trade Tribunal's determinations, reports of the Auditor General and internal audit reports of various departments. We also sought advice from a number of government departments and supplier associations.

Under the leadership of the Deputy Ombudsman we listed and set possible priorities for a broad spectrum of issues, in categories such as:

- legislation, regulations and policy;

- delegated authorities;

- departmental governance/strategic planning;

- communications;

- contracting processes;

- contract auditing and reporting; and

- procurement/contracting staff.

We then assessed our list to identify:

- the issues identified by our office as posing the greatest risk to the fairness, openness and transparency of the federal procurement system; and

- the issues that would be of most common interest to suppliers, departments and parliamentarians.

Finally, recognizing that we are a new office, we examined some very pragmatic factors:

- the availability and experience of internal and external resources;

- our ability to complete reviews in a timely fashion; and

- the complexity of possible review topics.

This multi-layered process led us in our first year to undertake reviews in four areas:

- Procurement challenge and oversight

- Supplier debriefings

- Advance Contract Award Notices (ACANs) and

- Mandatory Standing Offers (MSOs)

Procurement practice reviews may also be initiated during the course of the year based on facts or emerging issues and concerns that were not known at the time of the yearly planning exercise. For example, in May 2008, the Office was contacted by a supplier who made several allegations about the Correctional Service Canada's (CSC) CORCAN Construction program.

Further to discussions with CSC senior management, it was agreed that CSC would engage a private firm to review the allegations and report findings.

This section presents summaries of all of these reviews. The complete reviews will be posted on our Website.

Procurement Challenge and Oversight

According to the 2007 Purchasing Activity Report, departments and agencies of the Government of Canada spent $14,257,457,000 on 339,401 contract awards for goods, services and construction needed to deliver programs to Canadians.

The Treasury Board (TB) Contracting Policy clearly states that departments and agencies, unless specifically excluded by an Order in Council, are responsible for ensuring that adequate control frameworks for due diligence and effective stewardship of public funds are in place and working. More specifically, the Policy encourages contracting authorities to establish and maintain a formal challenge mechanism for all contractual proposals and recognizes that this mechanism could range from a formal central review board to divisional or regional advisory groups, depending on the departmental organization and magnitude of contracting.

The procurement challenge and oversight function is a key component of the broader set of management controls that are used to ensure the sound management of government procurement. In many departments, the principles of fairness, openness and transparency in procurement are safeguarded through oversight, review and monitoring by a senior procurement review committee. Depending on the mandate given to this committee, it can play a role in ensuring that all departmental actions in respect of the procurement process, including selection of the procurement strategy (e.g. use of Advance Contract Award Notices (ACANs)), evaluation criteria, contractual disputes, supplier debriefing and vendor performance, are carried out in accordance with policy and legal requirements.

There are two main reasons why having an effective procurement challenge and oversight committee function is important. First, the committee has a role in assessing corporate risks, which includes ensuring that all procurement activity is compliant with the relevant laws, regulations, trade agreements and policies and fulfilling the government's commitment to fairness, openness and transparency in procurement. Second, for all contract spending from a financial perspective, the committee should ensure that the requirement is justified and represents good value for money on behalf of all Canadian citizens.

The objective of our review was to examine departmental practices related to the committee responsible for the procurement challenge and oversight function at the senior departmental level. Through our review, we also wanted to identify effective practices that could be shared among government departments.

Nine departments and agencies were selected for this review. Eight of these organizations are governed by the aforementioned TB policy requirements relevant to procurement and contracting. Canada Revenue Agency has unique authorities in its enabling legislation and therefore is not governed by these policies.

We focused our review on the organization of and processes used by the most senior committee responsible for the procurement challenge and oversight function within each department. We conducted interviews with senior departmental officials and examined supporting documentation such as the committee terms of reference and sample submissions reviewed by them for the period from April 1, 2007, to March 31, 2008.

The nine departments and agencies included in our review carry out the challenge and oversight function by means of a senior departmental committee or board in combination with other procurement controls and committees. We found the roles of these committees as well as their stage of development varied, and the way they conducted their business differed considerably. There are some essential characteristics that the Office of the Procurement Ombudsman (OPO) recommends be considered in the creation and operation of these departmental committees. These are set out later in this Executive Summary.

Our findings indicate that Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC), Environment Canada (EC) and the Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) had well-established senior review committees governing the procurement challenge and oversight function. Further, they demonstrated the use of performance measures to assess their effectiveness and continuing efforts to improve the function within their respective organizations.

The Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), a much smaller agency, demonstrated a sound procurement management control framework, yet used an entirely different model appropriate for an agency of its size. In this model, the senior procurement review committee is responsible for providing direction and support for the development of CIHR's procurement framework. The review of procurement submissions at a transactional level is completed by the Manager of Procurement and procurement personnel, with transactions over $1 million reviewed by the Chief Financial Officer.

Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA), Industry Canada (IC) and Public Works and Government Services Canada (PWGSC) were operating senior procurement review committees consistent with their existing mandates. Both IC and PWGSC were actively pursuing improvements to strengthen their senior review committees. PWGSC and CIDA have stated that they intend to use the results of the Office of the Procurement Ombudsman review to address areas requiring improvement and incorporate identified "best practices" into their procurement management and oversight frameworks.

Finally, the Department of Justice (DOJ) and Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness Canada (PSEPC), both at the early stages of establishing senior procurement review committees, appear to be on track to have a strong central procurement challenge and oversight function. At the time of our review, both had recently developed terms of reference for their review committees. DOJ has advised that shortly after the completion of our field work their senior review committee became fully operational. PSEPC's senior committee was to be fully operational in May 2009 upon completion of training of its members.

All nine organizations reviewed have established terms of reference for their senior procurement review committees. Of the eight committees that have responsibility for conducting individual procurement submission reviews, six conduct their reviews at the procurement planning stage. One of the committees conducts its reviews at various procurement stages from planning to pre-contract award, depending on potential risks, as determined by the Director of Contracting. One committee conducts its reviews at the pre-award stage. We consider the completion of reviews at the planning stage to be an effective practice that can help departments reduce procurement risks before publishing solicitation documents that reflect the government's intentions.

Our review revealed that the criteria for submitting procurements for review varies depending on the individual department's risk profile and the existence of other controls such as investment review committees, compliance control functions and internal audits. Common examples of review criteria include dollar thresholds, types of procurement (e.g. goods versus services, competitive versus sole source), risk factors such as changes in scope, potential for disputes and contract ratifications. It was noted that some departments defined their review criteria using terms such as "significant plans" or "significant ACANs." We believe that such criteria are unclear and should be supported by an explanation of the relevant risk factors.

We determined from our review that generally the committee membership comprised senior management and was multidisciplinary, with senior financial and legal representatives participating as regular members of most committees. By having such very senior departmental personnel on the committee, the departments ensure that procurement submissions undergo the type of scrutiny that only senior management personnel with experience and a department-wide perspective can bring.

Based on a detailed examination of information submitted to the senior procurement review committees in six of the nine departments, we concluded that, as a rule, the committees were provided with appropriate information for decision making. The six organizations require that a template/checklist be completed by the submitting branch or directorate to ensure the procurement submissions tabled for review address key departmental risk issues and are recommended by the submitting directorate or branch.

We did note specific procurement issues that can benefit from further attention by these committees to assist in the mitigation of procurement risks. From our review of sample procurement submissions, we observed that information on past vendor performance was not provided to the committee. In addition, in our review of committee meeting minutes and records of decisions, we did not observe records of discussions of past vendor performance during contract periods.

The terms of reference for CRA's senior procurement review committee states that the committee reviews reports from previous procurements to analyse vendor performance.

We also noted, that in cases where poor vendor performance has been confirmed, PWGSC's Vendor Performance Policy (currently under review) calls for reasonable measures to be taken to prevent future problems. The Policy further stipulates that bids received from vendors that are debarred or suspended from doing business due to poor performance will not be considered for evaluation. In our opinion, the senior procurement review committee should be provided with assurances that the terms of this or any similar vendor performance policies are being implemented. More specifically, the committee should be provided with assurances that procurement solicitation documents and evaluation procedures will ensure that the terms of any restrictions or conditions imposed on a vendor as a result of poor performance are being complied with for all suppliers responding to the solicitation.

Further, from the samples reviewed, only one of the procurement submissions that involved more than one department was duly signed off by the departments concerned. We believe that where multiple departments are involved in the procurement, it is important to consider whether the proposed procurement actions are supported by all departments involved.

We also observed that while most committees require that they review procurement submissions where the proposed procurement process includes the use of an Advance Contract Award Notice, some do not. We believe that such procurements pose a special risk and all departments should establish risk indicators based on materiality and complexity, and require that all procurements meeting the risk profile, especially those that use ACANs, be reviewed by the committee.

In conclusion, we are generally satisfied with the progress made to establish effective procurement oversight committees. Through their membership and activities, these committees are working to ensure the openness, fairness and transparency of the procurement system and thereby strengthening the confidence of Canadians in government procurement.

The following practices are viewed as effective means of increasing the confidence of Canadians in procurement by improving oversight in departments. OPO recommends that in the creation and operation of these committees certain essential characteristics be prevalent:

- Committees should have comprehensive and objective terms of reference.

- Committees should include members who are multidisciplinary and who understand the procurement process and have an appreciation of the risks involved.

- Departments should establish risk indicators based on materiality and complexity, and require that all procurements meeting the risk profile, especially those that use ACANs, be reviewed by the committee.

- Committees should conduct their reviews at the outset of the procurement process (planning stage).

- Information submitted to these committees should be sufficient so as to ensure sound and effective decision making.

- Procurement submissions involving more than one department should be duly signed off by the departments concerned.

- Committees should be provided with assurances that procurement solicitation documents and evaluation procedures will ensure that the terms of any restrictions or conditions imposed on a vendor as a result of poor performance are being complied with for all suppliers responding to the solicitation.

- Committees should have the means to ensure they are receiving all procurement submissions included in their mandate.

- Committees should monitor the results of their decisions.

- Committees should have the means to judge whether or not they are operating effectively.

Our review also gave us an opportunity to observe additional effective practices, which departments may find helpful in strengthening their own oversight function. Departments listed in parenthesis are those where we noted these practices:

- Updating the terms of reference on a regular basis ensures that information is always current. (AAFC, CIHR, CRA, EC, IC and PWGSC)

- The use of a procurement checklist/template ensures that submissions presented for review address key departmental risks. (AAFC, CIDA, CRA, EC, IC and PWGSC)

- A series of supplementary questions, such as those used by Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, are useful to ensure that the submission is comprehensive and that officials presenting submissions have turned their minds to all considerations. These questions are in addition to what is provided in the procurement submission template.

- A streamlined review process for low risk procurement submissions is very important and incorporates sound risk management processes and appropriate use of resources. (CRA, EC and IC)

- The committee is supported through a computerized system that provides a tracking function to determine the status of the decisions it makes. (AAFC, CRA and EC)

- The committee has a means to "flag" contracts coming up for renewal to ensure renewal of contracts is not automatic, and options are exercised with due diligence. (AAFC, CIDA, CRA and EC)

- The committee measures whether through its actions there are improvements or deterioration in the procurement activity of the department or agency. (AAFC, CRA and EC)

- The committee tracks the stage in the procurement review process where the procurement submission is, in order to apprise clients of the status of their requirements. (CRA)

All departments and agencies involved in this review have been provided an opportunity to review this report and their comments have been taken into consideration in finalizing this chapter.

Supplier Debriefings

Debriefing is the process by which suppliers are given the results of the evaluation of their bid on competitive procurements. Information can be provided to a bidder by telephone, in writing or through a face-to-face meeting.

Information disclosure for debriefings is encouraged by a variety of legislative, regulatory and policy frameworks. Debriefings also make good business sense.

The Financial Administration Act (FAA) provides Treasury Board the power to set rules relating to the disclosure of basic information on government contracts valued in excess of $10,000. The Treasury Board Contracting Policy states that debriefings should be provided to unsuccessful bidders, and it is specific in what can be disclosed. The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and the World Trade Organization – Agreement on Government Procurement (WTOAGP) include requirements in more general terms to disclose information to unsuccessful bidders. The Access to Information Act identifies what information cannot be disclosed to a third party, such as commercially confidential information.

All of these instruments promote fairness, openness and transparency in the procurement process.

Under government policy, debriefings should be provided to suppliers, upon request. Our consultations revealed that some suppliers are unaware they may request a debriefing and consequently they have not received one. Others who have received debriefings feel frustrated by a lack of what they consider relevant and adequate feedback. This may be because suppliers have not been made aware of the legal obligations and constraints that procurement personnel are working under, or because some of the requested information cannot be provided due to commercial confidentiality.

We reviewed the debriefing and disclosure practices of six government departments and agencies: the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA), Citizenship and Immigration Canada (CIC), the Correctional Service of Canada (CSC), the Department of National Defence (DND), Indian and Northern Affairs Canada (INAC), and Public Works and Government Services Canada (PWGSC).

We note that procurement personnel have to take into consideration the various statutes and applicable departmental policies related to debriefing and information disclosure, which are not aligned, leading to differences in interpretation and application. This has contributed to the perception among suppliers that federal government procurement may not be being carried out in a fair, open and transparent manner and has eroded trust and confidence – the opposite of the government's objective.

We found that no mechanism exists in government to collect information, analyze, monitor, report and ensure continuous improvement in the process, so there is little statistical data on the number of debriefings and their effectiveness.

Our review indicates that there are no consistent standards across and within government departments for the content, nature and extent of debriefings. Procurement personnel do not have a "safe zone" (parameters as to what information can and cannot be disclosed) in which to operate. However, CIDA, INAC, and PWGSC have made significant efforts to inform bidders of their right to request a debriefing and have developed materials to guide their procurement personnel in this area. We also note that CIDA and PWGSC provide-point specific disclosure standards to assist their procurement personnel in addressing the debriefing challenges; these are available on their respective departmental websites.

Some procurement personnel believe that detailed debriefings may provide grounds for legal actions and appeals so they tend to limit information they disclose to mitigate the risks of a formal complaint. This has contributed to the development of risk-averse behaviour in federal government procurement and exacerbates the frustration of both suppliers and procurement personnel.

Giving suppliers more consistent information, however, should reduce the number of challenges and complaints. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) noted in its 2007 report that the UK had been successful in this regard and that, "although the causality between the introduction of detailed debriefings and legal reviews cannot be proven, there has been a sharp decrease in the last decade in the number of reviews."

Most procurement personnel recognize that it is beneficial for suppliers to receive a debriefing. However, most are also under the impression that these debriefings must be delivered through face-to-face meetings. One concern expressed to OPO was that publicizing the right to request a debriefing and delivering more-detailed debriefings may increase the demand for debriefings and place greater strain on procurement personnel at a time when the resources of the procurement community are severely stretched. While we understand the challenges, we wish to emphasize that capacity issues cannot override suppliers' right to know why they were not successful and how to improve their future bids. We believe that these concerns can be addressed by departments and agencies establishing bid information disclosure standards and methodologies that create an understanding of what, when and how information is disclosed.

For the most part, specialized training in communication on how to give "bad news" to unsuccessful suppliers is not provided consistently across government. There is no evaluation done to ensure procurement personnel have the necessary skills and competencies to conduct debriefings. The quality of debriefings is largely dependent on the perspective and experience of the procurement personnel involved. Inconsistent practices may lead to inconsistent messaging which can reinforce the perception that all suppliers are not being given information in an equal manner. This may contribute to the escalation into disagreement, confrontation and subsequent formal complaint.

The lack of awareness of the importance of debriefings may be a factor in procurement personnel's not informing bidders of their right to request a debriefing and failing to inform them of the outcome of a solicitation in a timely manner.

By definition, a competitive procurement process involves more than one bidder. Consequently, for each contract awarded to a successful bidder, there is usually at least one supplier that has "lost." There is, therefore, the inherent risk that one or more suppliers will be unhappy with the outcome of the process. This situation may discourage suppliers from competing for government contracts, the government itself loses – it faces significant challenges in attracting and retaining suppliers.

Debriefings benefit both the government and suppliers. A debriefing allows suppliers to judge how fairly they have been treated and increases their confidence that the procurement process has also been open and transparent. By acknowledging suppliers' investment of time, effort and resources, it may encourage them to do business with the government again. A debriefing could also improve their understanding of how to prepare a bid, and identify areas for improvement to increase their chances of success in winning future contracts.

In addition, through a debriefing, the government may obtain information from bidders as to how procurement practices could be improved in future.

An effective debriefing allows the government to improve its general communications with the supplier community, increasing the likelihood that contracts will be awarded in an atmosphere of cooperation and mutual respect. This should minimize the likelihood of delays and legal challenges and assist the government in meeting its program needs; it should also reduce the financial strain on suppliers and save money for taxpayers.

The UK Office of Government Commerce (OGC) has led the way in raising the debriefing bar. Its report acknowledges the fact that the rewards (benefits) outweigh the risks. The OGC analyzes the debriefing process and provides guidance, advice, tips and instructions to its procurement personnel with a view to establishing a reputation as a fair, open and ethical buyer.

Suppliers that have expended resources to bid on government procurement should have the right to know whether and why they were successful or not, and must know that they can request a debriefing to obtain that information. However, to manage expectations, procurement personnel and suppliers should know what information they can expect to give and receive following a competitive procurement.

The government does not want to discourage suppliers from submitting bids. Quite the contrary – it wants to retain and increase its supplier base to ensure competition, which will result in lower costs, better quality goods, services and construction, and a greater assurance of value for money in the expenditure of public funds.

To achieve this, action is needed by departments and agencies to set in place standards to:

- inform suppliers of their right to request a debriefing and recourse mechanisms;

- develop consistent core principles and an approach (creating a "safe zone") to ensure suppliers and procurement personnel have a clear understanding and expectation of what a debriefing will or will not include;

- establish clear instructions on options for delivering a debriefing, such as by telephone, in writing or face-to-face, and tailor the method to the complexity and materiality of the procurement; and

- ensure procurement personnel have the appropriate skills and are adequately trained.

PWGSC should develop a standard approach for debriefings. Once established, other departments and agencies may wish to adapt this for their own use based on their operational needs.

The Office of the Procurement Ombudsman firmly believes that the implementation of these recommendations will significantly enhance suppliers' perception of fairness, openness and transparency and help to strengthen the trust and confidence of Canadians in the federal procurement process.

All departments and agencies involved in this review have been provided an opportunity to review this report and their comments have been taken into consideration in finalizing this chapter.

Advance Contract Award Notices

The contracting objectives of the government of Canada include the commitment to take measures to promote fairness, openness, and transparency in the bidding process when acquiring goods, services and construction.

According to the Government Contracts Regulations (GCRs), soliciting bids to select a supplier should be the norm. However, the GCRs permit entering into a contract without soliciting bids under four exceptions, generally described as: pressing emergency; estimated contract value under specified dollar thresholds; not in the public interest to solicit bids; and only one supplier capable of performing the contract.

Trade agreements also contain procurement obligations and include "limited tendering" provisions, where the government can enter into a contract without soliciting bids (e.g. to protect patents, copyrights or where there is an absence of competition for technical reasons).

Contracts awarded without soliciting bids are known as "directed contracts," and these may be awarded with or without providing advance notice to the supplier community of the intention to award a contract to a pre-identified supplier. Directed contracts may pose risks to the fairness, openness, and transparency of the procurement process. Consequently, stringent controls and other measures should be prescribed to minimize and manage those risks.

An Advance Contract Award Notice (ACAN) policy was one of the measures introduced by Treasury Board (TB) to strengthen the transparency aspects of directed contracts. It is used when the government has reasonable assurance, but not complete certainty, that only one supplier can meet its requirement. The process associated with ACANs provides other potential suppliers, unknown to the government, an opportunity to demonstrate they are also capable of fulfilling the government's requirement by submitting what is known as a Statement of Capabilities. If a Statement of Capabilities meets the requirements set out in the ACAN, the department or agency must proceed to a full solicitation process in order to award contract.

During the three-year period from January 2005 to December 2007, the ACAN process was used for approximately $1.7 billion, or 4.3% of the total dollar value of government contracts over $25,000 (the threshold for soliciting bids under the GCRs).

There are inherent risks, under the current framework, when awarding a directed contract by means of an ACAN. For instance, the publication period allows other potential suppliers time to submit a Statement of Capabilities. These periods should be reasonable, in keeping with the complexity and value of the requirement.

If suppliers are not provided sufficient time to prepare a measured response, it can have a negative impact on the fairness, openness and transparency of the process.

The TB Contracts Directive, which requires TB approval to enter into or amend certain contracts, has been separated into three categories which correspond with the risks associated with awarding a contract. At one end of the spectrum, where the contracting process is open to all potential suppliers, departments have the authority to award contracts up to their highest contracting limits – typically $2 million for services. A lower contracting limit – typically $400,000 for services – is assigned to contracts where a minimum of two bids has been sought. At the other end of the spectrum, where competition is truly either not possible (e.g. patents, copyrights) or not feasible (e.g. not in the public interest), the contract can be awarded without advance notice and, accordingly, departmental contracting authorities are limited to much lower dollar values – typically $100,000 for services.

Since the TB Contracting Policy states that directed contracts awarded after publishing an ACAN are deemed to be competitive, procurement personnel can award contracts using the highest competitive contracting approval authorities without necessarily undergoing review by higher-level managers or committees. This can increase the risks to the Government, as senior management may not be involved in approving the use of ACANs.

The objectives of our review were to identify effective practices and areas for improvement of the fairness, openness, and transparency of ACANs. The focus of our review was to examine the consistency of departmental policies with TB policies and related guidelines and to examine departmental practices related to implementation and risk management, including reporting on activity levels and usage.

Our review covered ACANs issued from January 2005 to December 2007, and included the Canada Revenue Agency (CRA), the Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO), the Department of National Defence (DND), and Health Canada (HC). We also examined ACANs issued by Public Works and Government Services Canada (PWGSC) on behalf of these departments.

The four departments under review are governed by the aforementioned GCRs and TB policy requirements relating to procurement and contracting. CRA, however, has unique authorities derived from the Agency's enabling legislation – authorities that are separate and distinct from the authorities set out in the TB Contracts Directive, but with a similar structure in terms of how contracting authorities are applied to competitive and non-competitive procurement processes.

We found that most departmental policies are consistent with the TB Contracting Policy with respect to ACANs, with three notable differences.

According to TB, an ACAN is to be published for a period of not less than 15 calendar days. DND takes it one step further by requiring ACANs be published for a minimum of 22 days when the procurement is subject to the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and World Trade Agreement Organization – Agreement on Government Procurement (WTO-AGP).

TB also states that, if no valid Statements of Capabilities are received during the 15-day publication period, the contract may be awarded to the pre-identified supplier. PWGSC not only meets the TB Contracting Policy requirement, its policy further states that when a Statement of Capabilities is received after the ACAN closing date but before the award of the contract, it must still be considered prior to proceeding with the contract award. PWGSC's policy is based on the fact that, if procurement personnel become aware of another potential supplier at any time before the award of a directed contract, the statement "only one supplier is capable of performing the contract" is no longer valid and proceeding with contract award contravenes the GCRs. The difference in the wording of the two policies is important, as in some cases many months can elapse between the closing date for an ACAN publication and the actual award of the contract due to the complexity of negotiations, for example.

These different approaches may have a negative impact on the perception of fairness, openness and transparency as the same supplier may be treated differently depending on whether the procurement is processed by PWGSC, DND or another department.

We recognize that there are attendant risks regarding the consideration and potential acceptance of a Statement of Capabilities up to contract award. However, we believe some of those risks could be mitigated, for example, by clearly stipulating in the ACAN that the government will consider Statements of Capabilities up to contract award.

However, there is an additional unresolved operational risk. Suppliers may ignore the closing date of the ACAN and delay the submission of their Statements of Capabilities until a much later date (but prior to contract award). This could prolong the process and cause significant delays in meeting operational requirements.

While we understand PWGSC's reluctance to advertize this practice, this may provide an unfair advantage to some, as all suppliers may not have equal knowledge of this extended period to submit Statements of Capabilities.

Finally, while TB only requires that the rejection of a Statement of Capabilities be reviewed by a different official, PWGSC and CRA require this review to be carried out by an official at a higher level than the one who approved the publication of the ACAN. In our view this is a more effective practice which other departments may want to adopt, based on a risk assessment of their procurement process.

With regard to the practices related to the implementation of the ACAN process, we selected a judgmental sample of procurement files from the agency and departments subject to this review, where an ACAN was issued. Our review revealed that the majority of files were inadequately documented and many lacked support for invoking one of the GCRs exceptions to soliciting bids, or using limited tendering provisions under the trade agreements.

The TB Contracting Policy and CRA's Contracts Directive stipulate that ACANs should not be published when the government is unable to accept a Statement of Capabilities from a potential supplier. We expected, as a good business practice, that most of the procurement files would include documentation to indicate that some form of market research had been conducted to ascertain if more than one supplier could fulfill the requirement and to substantiate the subsequent decision to publish an ACAN. However, we found that this was not the case.

We are particularly concerned by the significant number of cases where the documentation showed that the government was dealing with only one supplier because there was a pressing emergency, it was not in the public interest or because the supplier owned the intellectual property rights, and, by definition, the government was unable to accept Statements of Capabilities from potential suppliers.

Based upon our review of procurement files and our discussions with suppliers and public officials, it appears that the TB Contracting Policy stipulation that the ACAN be published for a minimum of 15 days is, for the most part, being implemented as a maximum. Our review shows a range of recent ACANs between $32,000 and $42 million, all of which were published for a 15-day period. We would have expected that some of the more complex requirements, which may require suppliers to consult with their affiliates in Canada or abroad or where two or more suppliers may wish to form a joint venture, would have been given more than a 15-day window of opportunity to respond.

Based on a PWGSC report on its use of ACANs when contracting for itself and on behalf of other government departments, there is very limited supplier participation in PWGSC's ACAN processes. Statements of Capabilities are received in about 7% of cases, of which, only half are accepted.

To date, we have not been made aware of any analysis that has been carried out to ascertain the reasons for this low rate of supplier participation and its effect on the fairness, openness and transparency of the ACAN process.

We noted instances where some procurement personnel started discussions and shared information with the pre-identified supplier before the closing of the ACAN publication period. In our opinion, this poses a risk that the supplier may start work, or incur costs preparing to start work, prior to contract award.

PWGSC informed us that the practice of negotiating with potential suppliers is not contrary to government guidelines and that suppliers clearly understand that these are preliminary negotiations and they are not to start work before being awarded a contract; if they do so it would be at their own risk. PWGSC has also stated that they are not aware of any situations where early negotiations created the risk of unfair advantage to potential suppliers.

In our view, commencing negotiations with a single supplier prior to the ACAN closing date raises questions about the fairness and openness of the process. Should a Statement of Capabilities be accepted and lead to a competitive process, there is a risk that all potential suppliers may not be privy to the same level of information at the same time. This practice would not be allowed during a traditional or electronic competitive process.

We fully support the view that the principles of fairness, openness and transparency and the objective of obtaining best value for Canadians are best served by open competition for government contracts. We also recognize that there are occasions when open competition is not feasible and a directed contract is the appropriate course of action.

The government recognizes that directed contracts pose risks. They could be perceived as a source of preferential treatment, diminished access to all suppliers, and challenges to achieving value for money in the expenditure of public funds. However, by assigning significantly higher contracting approval authorities to directed contracts awarded using the ACAN process – with potentially less oversight – the government has diluted a major control mechanism to mitigate those risks.

We believe that there is a need to rethink policy requirements related to ACANs, in conjunction with the several initiatives the government is currently working on to streamline procurement.

We recommend the following:

- PWGSC should develop effective practices for its own use, which other departments and agencies may wish to adapt for their use, based on their operational needs. The practices should be designed to:

- reinforce compliance with government documentation standards, to support all phases of the procurement process;

- clarify that, although there is a minimum posting period for ACANs, the contracting authority should determine the individual posting period based on various risks associated with the requirement, including complexity and materiality; and

- since, from a contracting authority perspective ACANs are deemed to be competitive, provide guidance to procurement personnel that negotiations should not commence with the pre-identified supplier before the closing of the ACAN publication.

- PWGSC should undertake policy research related to the timeframes during which Statements of Capabilities can be received and assessed. PWGSC should attempt to find a viable solution to operational concerns resulting from the implementation of this policy, while maintaining the fairness of the ACAN process.

- Given there are three levels of contracting authority limits (the lowest contracting authority limit assigned to non-competitive contracts, a higher limit for traditional competitive contracts and finally the highest limit being assigned to electronic competitive contracts), TB may wish to examine the appropriate limits for directed contracts awarded using an ACAN, based upon risk considerations.

- As reported in the summary of the Procurement Practices Review on Procurement Challenge and Oversight Function, of the OPO's first Annual Report, 5 of 9 departments have their senior review committees approve procurements where contracts are to be directed using the ACAN process. We believe that such submissions pose a special risk, and we recommend that departments:

- establish risk indicators based on materiality and complexity, so that all directed contracts using ACANs that meet the risk profile would have to be approved by the senior review committee responsible for the procurement challenge and oversight function.

Subsequent to the completion of our review, we were informed by CRA that they have published a new procurement procedures document that includes instructions to procurement personnel to use longer posting periods for ACANs when the requirement is of such scope or complexity as to require additional time for the preparation and submission of Statements of Capabilities.

The agency and the departments involved in this review have all been given an opportunity to review this report, and their comments have been taken into consideration in finalizing this chapter.

Mandatory Standing Offers

In Budget 2005, the Government announced measures to help lower federal government procurement costs by using the large size of the federal government to get the best possible price. Accordingly, it became mandatory for all government departments to use Standing Offers (SOs) or other methods of supply put in place by Public Works and Government Services Canada (PWGSC) to purchase common goods and services ("commodities"). In April 2005, Treasury Board (TB) revised its Contracting Policy to make the use of SOs mandatory for 10 commodities.

As a common service organization and the government's main contracting arm, PWGSC then developed a policy to take a government-wide approach whereby departments are not to put their own SOs in place unless required under exceptional circumstances, as this would defeat long-term benefits and savings.

This review covered the period from April 2005 to August 2008. For calendar year 2007, the total volume of business through call-ups against SOs amounted to approximately $1.5 billion. The 10 mandatory commodities accounted for 57% of this total. We limited the scope of our review to PWGSC as SOs for the mandatory commodities are put in place and managed by PWGSC alone. Given the overall complexities and characteristic of SOs, other methods of supply such as Supply Arrangements or multi-departmental instruments were not included in our review.

The main objective of this review was to identify effective practices and areas for improvement with respect to the fairness, openness and transparency of government procurement. In that regard, we focused on suppliers' access and PWGSC's reporting of departments' usage of SOs. We were then able to formulate some initial impressions of mandatory SOs and to examine in greater detail the reporting and analysis used to support the management of three specific categories of commodities: Vehicles, Fuels and Human Resource Support Services (HRSS).

Mandatory SOs affect many industries with very different business environments. This office intends to examine, in future reviews, the effects of the SO method of supply on the fairness, openness and transparency of government procurement over a number of years.

An SO is an offer from a supplier to provide goods or services at prearranged prices, with set terms and conditions. Under this method, suppliers are normally provided with an estimate of the quantity expected to be purchased during a specific period of time. Departments fill their specific needs by issuing subsequent contracts (call-ups) against these SOs, and as a result, suppliers are not normally required to compete again to meet individual government requirements.

Benefits of the SO method of supply include lower administrative costs and less need for government to carry inventory. It also provides a consistent approach for both the government and suppliers to conduct business at a reasonable level of effort and cost.

A supplier not successful in obtaining a mandatory SO has limited opportunity for doing business directly with the government, until such time as a new Request for Standing Offer (RFSO) is competed. This calls into question the fairness and openness of extending the initial period of an SO by exercising options over a long period.

The U.S. government uses a method of supply called Multiple Award Schedules, which bears some similarity to SOs. While this method has its own limitations, most Schedules are continuously open, unlike SOs, so suppliers can qualify at any time. In addition, goods and services can be added at any time to ensure the government has access to the latest technology. In our view, further consideration should be given to adapting some of the best practices of other jurisdictions to Canada.

Standing Offers have been the subject of much concern in the supplier community. For example, the Business and Institutional Furniture Manufacturer's Association (BIFMA) felt that the consolidation of requirements has made it more difficult for suppliers to access federal government business and that the government is moving from an inclusive to an exclusive approach, putting businesses and particularly small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) at risk.

On the other hand, PWGSC maintains "that Standing Offers actually can reduce order consolidation in many cases since they make it easier to award many smaller projects to multiple suppliers."

PWGSC issued a Policy Notification, which states that the term of a mandatory SO should typically be one year in length and those optional extension years may be included if required. The Department informed us that "this statement is a recommendation, and not a directive." It has further stated that it does not have a fixed standard for the duration of an SO and that the period of each one is established on a case-by-case basis.

We found that the initial period of the SO method of supply was one year for two of the ten mandatory commodities. One used another method, and for the remaining seven, the period ranged from more than a year to nearly five years with an average of just over two years.

During our review, we were informed that the time required to put SOs in place is usually six to nine months because of process requirements and the limited number of resources available within PWGSC to manage the commodities.

We found that this is one of the reasons SOs are being put in place for longer periods. While we understand the issue of administrative convenience, longer periods reduce access to government contracts for suppliers and could limit opportunities for obtaining the latest technology, improving quality and achieving savings from price adjustments.

We noted that the SO database report provided by PWGSC to assess the period of the SOs contained several anomalies, which resulted in the exclusion of observations on extension periods from our review. These anomalies can have a significant impact on any analysis done using this database.

PWGSC informed us that this database is not the only source of analytical information used by commodity teams for decision making, and that the Department is working to improve the accuracy of the data captured in the system. To address the data accuracy issues identified, the Department is upgrading training for procurement personnel to reflect the importance of good record keeping and monitoring data received.

Given the importance of the need for accurate reports on the duration of standing offers for planning and monitoring, we encourage the Department to analyze the database to ensure its integrity. Meanwhile, users of the outputs from this system, especially senior decision makers, should be made aware of its shortcomings. If the Department relies on better sources of information for decision making, then a cost-benefit study should be undertaken to see if the expenditure involved in maintaining and upgrading it should be continued.

With respect to the three specific categories of commodities, we found that mandatory SOs for Vehicles are competed on a yearly basis, those for Fuels are renewed every two years, while those for HRSS are based on a four-year cycle.

In our view, when SOs are competed, all suppliers must have access to reliable information to price their bids accordingly and ensure the "optimal balance of overall benefits to the Crown and the Canadian people." To achieve this balance and to support effective decision making in the management of this method of supply, solid analysis of the demand must be done by the Department.

We examined the process of recording call-ups for planning purposes. We considered the timeliness and quality of government reports on SOs.

The Contracting Policy recommends that call-ups against SOs be reported by all departments to PWGSC for consolidation. Some departments cannot readily provide this data as they do not have the appropriate automated reporting systems in place. PWGSC's preparation of the annual report on government usage is therefore not finalized until eight to nine months after the end of the reporting period. In addition, we noted that PWGSC has been unable to match over 30% of the data supplied by government departments to any active SO, leading us to question the reliability of the data and the effectiveness of the decisions made using these reports.

PWGSC informed us that "it has been working with client departments to develop an automated system, and hopes to eliminate this issue over the coming year."

PWGSC requests regular call-up activity reports from suppliers, as a condition for maintaining an SO, to assist the Department in tracking usage and forecasting future demand. Suppliers have informed us that they incur additional costs to prepare and submit these reports. With regard to the three categories of commodities we reviewed, we noted that the commodity team for:

- Vehicles has its own tracking system (as PWGSC is the main department issuing call-ups) and has other sources of information available to it, so it does not make use of supplier-generated reports;

- Fuels has developed annual "Previous Buy Information Reports" for departments to track usage and has access to other sources of information, so it analyzes only supplier reports to identify unusual patterns not aligned with forecasts from departments; and

- HRSS has access to various usage reports, including those from suppliers, but does not analyze any of this information.

This means that suppliers prepare and submit reports that are being ignored for the most part.

Vehicles and Fuels have effective practices to plan, develop and manage their SOs. These commodity teams make effective use of their own internal reports, industry publications, and department and supplier consultations to keep track of usage and market trends in order to forecast demand. The same does not appear to be true for HRSS.

All three commodity teams have resource challenges to varying degrees. Vehicles has six full-time procurement specialists to manage eight SOs. Fuels has eight full-time employees – procurement specialists and administrative staff – to manage approximately 70 SOs. HRSS currently has only one junior procurement specialist to manage approximately 80 similar SOs.

Interviews with PWGSC procurement personnel indicated that extensive work can be involved in the preparation and management of standing offers. Staff have stated that given the funding and labour pressures found within the procurement sectors, renewal efforts of SOs are sometimes limited, and that in some instances, they are not renewed as often as the Department would like. This may lead to concerns over accessibility for suppliers to these instruments.

Subsequent to the completion of our review, we were informed by PWGSC that it is now in the process of replacing the HRSS standing offer with a new instrument. This instrument is being developed after extensive consultation through working groups with both client departments and the supplier industry. The Department is confident that this tool has greater functionality than the previous tool, in particular with respect to accessibility for suppliers. For example, while HRSS had a four-year term, this tool allows for frequent refreshes (every 15 months) of the named suppliers and prices.

Recommendations

The procurement process should be driven by timely and accurate information in order to achieve the expected outcomes, efficiency and effectiveness. Implementation of the following recommendations should promote fairness, transparency and access for all suppliers, while improving practices that promote quality and innovation.

Based on our general observations related to the duration of SOs, we recommend that PWGSC:

- clarify its policy by establishing a set of key criteria to develop a standard for the duration of SOs that would strike a balance between government objectives and promote the principles of access, openness and fairness for suppliers;

- provide guidance and tools to assist its procurement personnel to implement the standard;

- once a standard is established, require that reasons for any deviation from the standard be fully documented and approved by a higher authority; and

- use current communications channels to inform the supplier community of its revised standard.

Based on our general observations related to the three specific categories, we recommend that PWGSC:

- take measures to improve the reliability of its SO database;

- work with departments to improve usage reporting information integrity and timeliness;

- analyze suppliers' reports when those reports are required to supplement other sources of information, and integrate the results into the decision making process;

- eliminate unnecessary reporting requirements for mandatory SO suppliers;

- develop and document processes for consistency to make use of information in order to effectively manage mandatory SOs; and

- ensure that its commodity management teams have adequate resources to effectively carry out planning, development and management functions.

The Department was given an opportunity to comment on this report, and its comments have been taken into consideration in finalizing this chapter.

PWGSC has informed us that it agrees with the primary thrust of the report in that procurement authorities should consider, in addition to other factors, fair and timely access to competitive processes for suppliers, and it will revise instructions to procurement personnel to emphasize this objective.

CORCAN

The Office of the Procurement Ombudsman (OPO) was contacted in May of 2008 by a supplier who made several allegations about irregularities of contract award and contract administration in the CORCAN construction services program at Correctional Services Canada (CSC).

A special operating agency (SOA) within CSC, CORCAN is mandated to provide employment training and employability skills to offenders in federal correctional institutions in support of Government of Canada social policy.

One of CORCAN's five business lines is CORCAN Construction, which has operations throughout the country, including Kingston, Ontario, the site to which the allegations pertain. The total value of CORCAN Construction expenditures in Ontario for 2007-2008 was $3.1 million.

CORCAN Construction employees and contract staff carry out and manage/oversee the various CORCAN Construction projects and the related training/employability elements. Contractors engaged by CORCAN Construction are required to supply skilled labour for offender training. In consideration for the supply of skilled construction labourers by the contractor, CORCAN pays the contractor at prescribed rates for construction trades plus a training charge. The construction projects provide inmates who assist in this work with training in order that they might acquire marketable skills to improve their future employment prospects.

The allegations concerned procurement issues related to the contractual arrangements put in place at the site in Ontario for the provision of construction services and offender training. These allegations involved:

- the misuse of supply arrangements (SAs) issued for the period of September 2006 to March 2008 (these SAs had a value of approximately $1.3 million for 2007-2008);

- the solicitation and awarding of a business-to-business (B2B) alliance agreement for March 1, 2008 to March 31, 2009 (valued at $2.3 million);

- the management weaknesses related to the use of the B2B agreement; and

- a potential conflict of interest in the operations and management of the B2B agreement.

The Procurement Ombudsman Regulations provide the Ombudsman with authority to review the procurement practices of departments in order to assess their fairness, openness and transparency and make recommendations for the improvement of those practices.

After making preliminary inquiries we decided to carry out a review of CORCAN contracting practices to examine the systems and practices related to the allegations.

The matter was then brought to the attention of CSC management, which expressed great concern about the allegations. It was agreed that CSC would engage a private sector firm to review the allegations and report its findings. OPO and CSC officials agreed to the following:

- The scope of the work and the review methodology would have to satisfy the needs of both CSC and OPO;

- CSC would present the report and related action plan to its audit committee;

- OPO would review the report and the supporting documentation it considered necessary; and

- OPO would disclose the significant observations in its annual report.

CSC commissioned a private firm to carry out the review, which was done in three phases. The report on the work done in the initial phase recommended three of the nine allegations for further review and determined the other six to be unfounded. Of these three, two relate to possible misuse of SAs, and one relates to the solicitation and implementation of the B2B agreement.

The second phase further examined the allegations and confirmed the misuse of SAs, issues with the solicitation and award process for the B2B agreement, problems with the use of the B2B agreement and a potential conflict of interest in the implementation of the B2B agreement.

The third phase reviewed the administration of the B2B agreement, and the report included recommendations for improving controls over the management of projects that would be conducted under such arrangements.

Based on our review of the file and the reports, we are of the opinion that there were significant flaws in the procurement practices, such as the:

- short bid solicitation period (three days – December 20–22, 2007);

- lack of an evaluation methodology in the bid solicitation;

- lack of appropriate controls to manage a known conflict of interest situation; and

- lack of required documentation in procurement files.

It also appears that the financial and contracting authorities were exceeded.

As a result, in our opinion, for the transactions under review, the fairness, openness and transparency of the contract award and administration processes have been seriously compromised.

We note that management acted in a responsible and prudent manner when OPO brought the matter to its attention.

Each allegation and review finding has been analyzed and addressed in a very detailed management action plan. The entire matter has been reported to the highest level and has been discussed by the Audit Committee. The action plan itemizes the policy, structural and operational changes that need to be made to prevent future breakdowns of internal control. We have been informed that CSC has dealt with the related Human Resources issues pertaining to potential conflict of interest.

From our review of the work done by the firm and the management action plan prepared by CSC management to address the review findings, we are satisfied that CSC management has adequately dealt with the specific allegations.

CSC has conducted further work and is satisfied that the issues arose from a breakdown in the system of internal controls and were administrative in nature and that there was no unlawful activity. CSC is also satisfied that no recovery action is required.

CORCAN had managed the B2B alliance agreement based upon the premise that it was not subject to the Government Contracts Regulations (GCRs) or the Treasury Board (TB) Contracting Policy. Following this review, CSC informed us of their conclusion that the GCRs and TB Contracting Policy do apply to this type of agreement, where goods and/or services are procured by CSC.

OPO recommendations

- CSC review its other CORCAN construction contracts to ensure that a systemic problem affecting fairness, openness and transparency in the procurement process does not exist and that no delegated financial or procurement authorities have been breached;

- CSC assess the need for training in the area of procurement, including construction services, and devise an appropriate action plan;

- CSC review, in consultation with the Public Works and Government Services Canada and the Treasury Board Secretariat, the appropriateness and legality of the B2B procurement method, including issues pertaining to the application of the Government Contracts Regulations, TB policy, and delegated departmental authorities.

CSC agrees with the recommendations in this report. The detailed actions are included in the body of the report.

Procurement Inquiries and Investigations

Our Procurement Inquiries and Investigations team is our day-to-day interface with the world and receives inquiries from the supplier and procurement communities, as well as from the general public. The team seeks the rapid resolution of any given situation and may launch a formal investigative process into complaints when warranted.

As noted earlier, our business model encourages suppliers to contact the relevant departments and try to resolve their issues directly before coming to the Office of the Procurement Ombudsman. Although our mandate provides us with the authority to carry out a simple or detailed investigation in response to a formal complaint, these investigations could take many months to complete. Our consultations with suppliers revealed that they are more interested in a speedy resolution to their issues than being drawn in a lengthy investigation process.

Under our business model, we encourage suppliers to discuss their issues with us and allow us the opportunity to find quick and acceptable solutions through informal means (such as making phone calls, sending emails or opening other lines of communication) before filing a formal complaint. This approach has resulted in positive results for all stakeholders and, over the long term, should improve relations between the government and its suppliers.

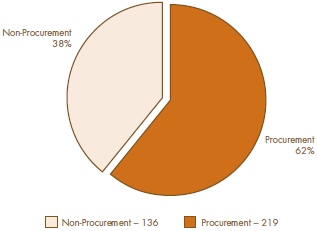

Since the Office became operational, we have been contacted 355 times. Of those initial contacts, more than one third were non-procurement related and outside of our mandate, such as taxation, pension and housing concerns. As we have learned in our discussions with other ombudsman offices, this is fairly typical.

Procurement Related Inquiries vs Non-Procurement Related Inquiries

Text description of this PRI vs NPRI is available on a separate page.

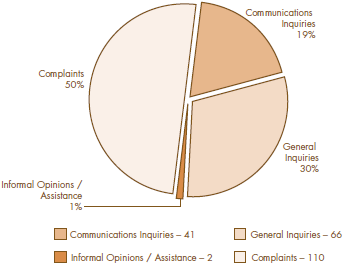

Procurement Related Inquiries

Text description of this PRI is available on a separate page.

We have divided the procurement related inquiries into several general categories:

- communications inquiries: including requests for speaking engagements, interviews and procurement advertising newsletters;

- general inquiries: regarding our mandate, regulations, how to do business with the government, and where government information may be found (e.g. Government Contract Regulations, Code of Conduct for Procurement);

- informal opinions/assistance: including advice on issues such as bid rigging or processes for disclosing information appropriately; and

- complaints: regarding the award or administration of contracts.

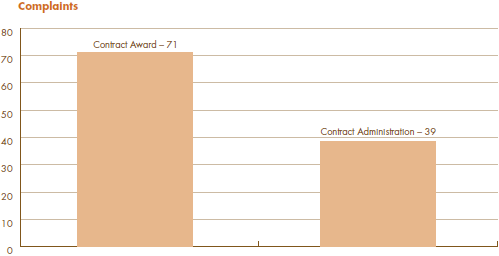

Complaints

We were not surprised that most of our contacts in our first year of operation were of a general informational nature. That being said, complaints dealing with procurement issues constitute our core activity and are vital to the task of improving federal government procurement.

In accordance with our mandate to investigate complaints, they have been divided into two broad categories: contract award – which includes all activities from bid solicitation to contract award; and contract administration – which includes activities such as contract amendments, monitoring progress, following up on delivery, payment actions, etc.

Text description of this Complaints Bar Chart is available on a separate page.

1. Contract award

Some of the complaints brought forward concern:

- security clearance process;

- solicitation process;

- debriefing;

- irrelevant mandatory requirements;

- cancellation of RFP for no apparent reason; and

- procurement strategy of standing offers.

2. Contract administration

Some of the complaints brought forward concern:

- late payments;

- no interest on late payments;

- subcontractor issues;

- standing offer extension;

- interpretation of terms and conditions (ADR); and

- termination for default.

We are pleased to report that of the 219 procurement related supplier contacts we received until March 31, 2009, the team has had to initiate only one formal investigation. At the time of writing this report, the investigation was not finalized.

We have been carefully analyzing the particular areas of procurement where the complaints seem to be originating. This information then is used as input for our future planning for practice reviews. This year, two of our reviews, Supplier Debriefings and Mandatory Standing Offers largely arose after concerns were raised by suppliers.

In our first year, a significant effort had to be put into explaining to suppliers and government officials the scope and limitations of our mandate relating to complaints. As the chart illustrates, 38% of the time the issues raised by suppliers with the Office were on non-procurement matters. In each one of these instances the team conducted the required research and provided the suppliers information on the most appropriate place in government to address their inquiry. In the more serious cases the Procurement Ombudsman has written to the relevant Deputy Minister(s) and brought the matter to their attention.

Given the success of our collaborative approach, we intend to follow the same business model in the coming years. This approach is based upon dialogue and consensus, but does not mean that we will not use our formal authority to launch investigations. Stakeholders – suppliers or government departments – should not underestimate our willingness and determination to use all the authority provided by our mandate to ensure the fairness, openness and transparency in government procurement.

Alternative Dispute Resolution Services

Given the significant number of contracts in which the federal government is a party, disputes between the government and its contractors are inevitable. When disputes arise during the performance of a contract, they have immediate negative repercussions and distract contractors and government officials from what their focus should be: the completion of the contract on time and within budget. For the contractor, disputes represent increased costs and raise reputational risks. For the government, disputes represent risks to timely contract completion and quality of deliverables. It is in all parties' best interests to have disputes resolved quickly and efficiently.

Suppliers and government departments now have a new avenue of recourse and can seek the assistance of the Office of the Procurement Ombudsman to help them resolve their contractual disputes. The Office has a legislated mandate to ensure that an Alternative Dispute Resolution process is provided for disputes relating to the interpretation or application of the terms and conditions of a contract. Prior to the creation of this program, no such neutral and independent office existed in government.

Before providing an ADR process, we encourage the parties to try to resolve the issue themselves by redirecting the contractor to the concerned department, if it has an established process, to have the matter resolved there. Given our business model, it was important for us to know whether or not departments had preexisting complaint resolution processes (which could include more formal dispute resolution services).

Research Project

During the course of the year, the Office undertook a research project to better understand the concerns of both the supplier community and government officials on the issue of contract complaints handling and dispute resolution services. The research project also served to inform the manner in which our ADR services would be delivered.

Our research indicated that there is significant concern among suppliers about the method in which disputes were handled. Supplier associations indicated that their members lacked confidence in the dispute resolution processes of government departments. They were particularly concerned about the lack of separation of duties of those initially overseeing the contractual process and those adjudicating disputes, and some suppliers even indicated that they chose not to bring disputes forward. The reluctance of contractors to bring forward disputes is leading some departments to conclude that there is no need to improve these practices.

As part of our research project, we chose ten departments of varying size and budget and met with contracting and program officials to discuss the policies and practices of these departments. We discovered that even though contract dispute resolution is addressed in the Treasury Board Contracting Policy, departments are at varying degrees of implementation of complaint handling and dispute resolution policies and processes. Departments did indicate they were seriously committed to early resolution of complaints.

Managing complaints before they become very serious and spiral out of control is in the best interests of both suppliers and government. We are supportive of strengthening this capacity in government departments and will work with departments on this matter. Where it is weak or non-existent, or where parties so choose, we are available to provide ADR services.

"…The Office of Procurement Ombudsman is positioned to provide an easily accessible point of contact within the federal infrastructure for resolution of procurement-related disputes or concerns."

– Jeff Morrison, president of the Association of Canadian Engineering Companies

Our Services

Given the existing environment, we have strived to create ADR services that:

- are fair, open and transparent, applied in a consistent and professional manner, and timely;

- constitute effective and useful communication to educate both parties, so that they are working with the same information;

- recognize and address power imbalances;

- provide access to and flexibility of appropriate options to resolve conflicts at every stage of the dispute;

- result in resolutions that are equitable and fair, and that both sides will honor; and

- satisfy both parties that they have been appropriately engaged in the process and involved in the outcome.

We developed our ADR services with the significant assistance of the Department of Justice's Dispute Prevention and Resolution services. The Department of Justice met with Office staff on several occasions in recent months and provided us with expert advice and information on the various mechanisms available to resolve disputes. With their guidance, we were able to select those dispute resolution options that best meet the objectives and the needs of suppliers and the government. We have also developed policies, procedures and templates for our internal use.

Our ADR service is a confidential and voluntary process. In order to facilitate a fair and quick resolution of contractual disputes, we offer three options:

- facilitation: a neutral third person – usually a member of the Office – establishes communication between the parties and seeks to encourage a dialogue so that both sides move towards an understanding of each other's position and a mutually acceptable outcome;

- mediation: a neutral third party (not a member of the Office) with substantial subject-matter knowledge provides assistance to both sides in an attempt to reach a mutually acceptable outcome; and

- non-binding arbitration: a neutral third person (not a member of the Office) hears both sides and renders a non-binding written decision on the dispute.

Both parties have to agree at the outset that they will participate in the process and share any associated costs. The parties can agree on the cost allocation between themselves. Also, each party will be responsible for its own expenses, such as those related to travel. There are no costs involved when a member of our office provides a facilitation service.

In accordance with the Procurement Ombudsman Regulations, once a request for ADR has been received in writing by the Office, we review the request and supporting information/documentation to determine if it is suitable for ADR. If it is, we seek the consent of the other party to the contract to participate in an ADR process.

If the other party agrees to proceed, we prepare a proposal for both parties that sets out the type of process best suited to their needs and our rationale for selecting it. The proposal also includes the conditions under which the ADR process will be carried out (e.g. scope, duration, location) and identifies any fees or expenses associated with a specific process, such as paying for the services of a mediator.

As of March 31, 2009, we have received only four requests for ADR services:

- one was withdrawn by the requestor before the office took any action;

- one was resolved through the use of facilitation;

- two are outstanding, pending further information.