Summary of the Findings of OPO’s Planned Procurement Practice Reviews conducted between 2018 and 2023

October 2024

On this page

- I. Introduction

- II. Background

- III. Results

- IV. Simplification

- V. Follow-up reviews

- VI. Conclusion

- VII. Next steps

- Annex 1—Departments reviewed under the 2018-23 Procurement practice review plan

- Annex 2—Standard review program

- Annex 3—Establishment of the 5-year Plan and examination methodology

I. Introduction

1. In 2018, the Office of the Procurement Ombud (OPO) initiated its 5-year Procurement Practice Review (PPR) Plan. Under this plan, the procurement practices of 17 federal departments were reviewed to determine whether evaluation criteria and selection plans, solicitation documents, and evaluation of bids and contract award, supported the principles of fairness, openness and transparency. This report provides a roll-up of key observations and results from the 17 completed reviews.

2. The mission of the Procurement Ombud (hereafter referred to as Ombud) is to promote fairness, openness and transparency in federal procurement. The Ombud’s mandate is established in the Department of Public Works and Government Services Act and requires the Ombud to:

- Review procurement practices: Review the practices of federal departments for acquiring goods and services to assess their fairness, openness and transparency, and make any appropriate recommendations to the relevant department for the improvement of those practices

- Review complaints related to contract award: Review complaints respecting the award of a contract for the acquisition of goods below $33,400 and services below $133,800 (values adjusted every two years), where the criteria of the Canadian Free Trade Agreement would otherwise apply but for the dollar values

- Review complaints related to contract administration: Review complaints respecting the administration of a contract for the acquisition of goods or services, regardless of dollar value

- Provide alternative dispute resolution services: Ensure that an alternative dispute resolution process is provided to parties to federal contracts, regardless of dollar value of the contract

3. In order to guide the office’s activities, OPO has defined 5 pillars that underpin its work, interactions with stakeholders, and delivery of the mission and mandate of the Ombud. These 5 pillars are the following:

- Diversity: Diversity is at the heart of OPO. It reflects people, views, and the commitment to stakeholders. OPO seeks to promote Diversity and Inclusion (D&I) both in the workplace and the community by applying a D&I lens to its mandated activities, including staffing actions, learning opportunities, research studies, and services that help diversify the federal supply chain. OPO strives to be a leader in the Government of Canada in promoting diversity and inclusion in both official languages.

- Simplification: OPO believes that simplifying procurement is essential to improve how federal procurement works for all Canadians. OPO drives progress in this area by providing simplification-focussed recommendations in it’s PPRs, and by highlighting examples of best practices and opportunities for streamlining the federal procurement process. Simplified procedures, templates and solicitation practices help promote competition and encourage a higher number of bids. OPO maintains that this results in better value for money for Canada and supports fair treatment of suppliers. OPO further supports simplification by examining internal processes and practices in order to identify operational efficiencies and opportunities to serve their stakeholders in a clear and streamlined manner.

- Transparency: OPO advocates for transparency as a means of increasing trust in the federal procurement system. OPO believes that departments must provide accurate information to Canadians in a timely manner to facilitate public scrutiny of decisions made and actions taken. Canadian suppliers equally require timely, accurate and unbiased solicitation documents to prepare responsive proposals. OPO promotes transparency through its reviews of federal procurement practices to ensure departments meet their duty to provide notice of intended procurements, publish accurate award information, and maintain appropriate records of key decisions made throughout the procurement process.

- Knowledge Deepening and Sharing: OPO undertakes independent examinations into root causes of procurement issues along with emerging issues impacting the federal procurement landscape. These Knowledge Deepening and Sharing (KDS) studies are not limited by the parameters of a specific review program or complaint, and their value resides in their flexibility. Through environmental scanning, OPO aims to identify key issues and trends in federal procurement and provide meaningful guidance to suppliers and federal departments. In addition, this analysis can be used to determine “reasonable grounds”, which form the basis of PPR activities. Delving into critical procurement topics through KDS studies promotes discussions and provides much needed guidance within the procurement community.

- Alternative Dispute Resolution: OPO provides Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) services (e.g., mediation as a quick and cost-effective way to resolve contract disputes. OPO’s ADR services enable parties to a federal contract to resolve issues and achieve a mutually agreed-to solution, while maintaining control over the process. OPO offers certified mediators to provide such services free of charge.

II. Background

4. A key component of the Ombud’s mandate is to conduct PPRs. These engagements are comprehensive, systemic reviews of the practices of federal departments for acquiring goods and services to assess their fairness, openness and transparency.

5. PPRs are conducted in a manner that considers multiple key elements of a department’s procurement activity, including contracts valued above the dollar thresholds which apply in OPO’s Reviews of Complaints related to the award of a specific contract. Through PPRs, OPO provides recommendations in areas that require improvement, and also highlights good practices that were observed and can be emulated by other departments. As one of the Ombud’s key priorities, opportunities for simplification are also highlighted. OPO also conducts follow-up reviews, roughly 2 years after the initial review is completed, which are designed to determine if departmental management action plans intended to address the Ombud’s recommendations have been implemented.

6. In October 2018, the Ombud approved the 5-year PPR plan to examine the 3 highest-risk procurement elements across the top 20 largest federal departments identified based on the value and volume of their annual purchasing activity ($100M or more in purchasing activity). The objective of these reviews was to determine whether procurement practices relating to evaluation and selection plans, solicitation and evaluation of bids and contract award were conducted in a fair, open and transparent manner. To determine this, OPO examined departmental procurement practices to assess whether they were consistent with Canada’s obligations under national and international trade agreements, the Financial Administration Act and regulations made under it, the Treasury Board Contracting Policy and, where applicable, departmental guidelines.

7. While 20 federal departments were initially included for review in the 5-year plan, this was reduced to 17 departments after the Treasury Board Contracting Policy (TBCP) was replaced by the Directive on the Management of Procurement (DMP) on May 13, 2022 after a 1-year transition period. Since the first 17 departments were tested using the rules established under the TBCP, it was no longer appropriate to test the remaining 3 departments using these same rules, or different rules and then seek to compare the findings of all 20 upon their completion. A list of the 17 federal departments reviewed is provided in Annex 1.

8. OPO conducted all PPRs using an established methodology that follows 3 standard Lines of Enquiry (LOE):

- LOE 1: To determine whether evaluation criteria and selection plans were established in accordance with applicable laws, regulations and policies

- LOE 2: To determine whether solicitation documents and organizational practices during the bid solicitation period were consistent with applicable laws, regulations and policies

- LOE 3: To determine whether evaluation of bids and contract award were conducted in accordance with the solicitation

9. The criteria supporting the above standard LOEs are included in Annex 2. OPO’s PPRs also included a section dedicated to simplification in order to identify both good practices and opportunities for improvement. By looking at the procurement practices of 17 departments over 5 years, OPO has been able to highlight many of these good practices as well as practices that should be avoided.

10. A total of 631 procurement files were reviewed across the 17 federal departments. Based on contracting data provided by the departments, OPO assessed competitive procurement files for contracts established under the contracting authorities of the departments reviewed. Selected files generally excluded low-dollar value contracts, construction contracts, non-competitive contracts and acquisition card activity. Further details regarding the establishment of the plan and examination methodology can be found in Annex 3.

III. Results

11. A total of 92 recommendations were issued to, and accepted by, the 17 departments reviewed. Figure 1 below provides a breakdown of the number of recommendations by LOE

| Line of Enquiry | Number of Recommendations | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| LOE 1: Evaluation criteria and selection plans were established in accordance with applicable laws, regulations and policies | 20 | 22% |

| LOE 2: Solicitation documents and organizational practices during the bid solicitation period were consistent with applicable laws, regulations and policies. | 26 | 28% |

| LOE 3: Evaluation of bids and contract award were conducted in accordance with the solicitation | 35 | 38% |

| Related to other observations | 11 | 12% |

| Total | 92 | 100% |

While the majority of recommendations were issued under one of the standard LOEs (81 of 92 recommendations), 11 recommendations pertaining to other observations were also issued. Details of the observations leading to the issuance of recommendations are included below and are presented under their respective LOE or other observations.

LOE 1: To determine whether evaluation criteria and selection plans were established in accordance with applicable laws, regulations and policies

12. Observations noted under LOE 1 accounted for 20 recommendations (22% of all issued recommendations). All departments reviewed had instances where mandatory criteria, point-rated criteria or associated rating scales were not clearly communicated. Instances of lack of clarity in the communication of selection methodologies were also observed in the majority of departments, as were instances of evaluation criteria not aligning with operational requirements. In addition, instances of evaluation criteria that were overly restrictive or appeared to favour the incumbent were observed in the majority of departments reviewed.

13. Regarding clarity of evaluation criteria, 35% of files reviewed (159 of 459 applicable files) across all 17 departments were found to include mandatory criteria that were not communicated in a clear, precise and measurable manner. This included cases where criteria made use of non-mandatory language (e.g., “should” instead of “must”), undefined terms (e.g., requiring experience but not defining the duration of that experience), and elements that could not be evaluated on a clear “pass or fail” basis at the time of bid closing (e.g., criteria that relate to the performance of the required services in the future). With respect to point-rated criteria, 28% of files reviewed (82 of 292 applicable files) across 14 departments were found to lack clarity in point-rating scales or in the criteria including, for example, the use of ambiguous terms and rating scales that did not clearly indicate how points would be awarded by evaluators. The use of ambiguous and undefined terms in evaluation criteria unnecessarily increases subjectivity and prevents bidders from understanding how their bids will be evaluated. It cannot be left up to bidders to guess the meaning of criteria, or for evaluators to struggle to interpret criteria or scoring grids during the evaluation process. Respecting lack of clarity in the communication of selection methodologies, 7% of files reviewed (40 of 540 applicable files) across 12 departments were found to provide incomplete or contradictory information regarding the selection methodology or provided no information regarding how selection would be made. Overall, the lack of clarity in evaluation criteria and selection methodologies is a common issue among departments reviewed that can undermine the transparency of the bid solicitation process and make it more difficult to defend decisions made against external challenges.

14. While not as significant or widespread, observations with respect to alignment with operational requirements were also noted, with mandatory evaluation criteria that were not aligned with the requirement in 5% of files reviewed (25 of 459 applicable files) across 9 departments, and point-rated criteria that were not aligned with the requirement or contained weighting factors that did not reflect the relative importance of the point-rated criteria in 3% of files reviewed (10 of 292 applicable files) across 5 departments. This included, for example, mandatory experience requirements found in the Statement of Work that were not assessed in mandatory criteria or that did not correspond to the experience requirements assessed in mandatory criteria; or point-rated criteria that awarded points for education or experience unrelated to the requirement. Evaluation criteria that do not align with requirements unnecessarily complicate the procurement process and create opportunities for bidders to make mistakes and for their proposals to be deemed non-responsive for failing to meet criteria that are not related to the work to be performed.

15. Evaluation criteria were found to be overly restrictive or appeared to favour the incumbent in 6% of files reviewed (26 of 469 applicable files) across 10 departments. Examples of overly restrictive criteria included requiring prior experience with the same department, and requiring experience that closely aligned with that of the incumbent. Such criteria result in restricting solicitations to a limited number of bidders, impacting both the openness and fairness of the processes. This can be linked to a trend OPO has observed over the last several years where competitive processes often result in only a single bid. Among the 17 PPRs conducted, OPO found that 33% of competitive solicitations reviewed resulted in only 1 bid. The use of overly restrictive criteria further deters suppliers from submitting bids as they will often decide it’s not worth the effort and expense of preparing a bid if they believe the solicitation favours a particular supplier.

16. To address identified issues under LOE 1, the Ombud issued recommendations that called for the implementation of measures such as establishing new or enhanced monitoring and quality control processes, ensuring the implementation of existing guidance, reviewing and updating internal guidance instruments, and implementing training for contracting and technical authorities to ensure evaluation criteria used in solicitations are clear, aligned with requirements, and not overly restrictive.

LOE 2: To determine whether solicitation documents and organizational practices during the bid solicitation period were consistent with applicable laws, regulations and policies

17. Observations made under LOE 2 accounted for 26 recommendations (28% of all issued recommendations). Observations related to the lack of clarity and incompleteness of information provided in solicitation documents, including issues with the description of requirements, were noted in the majority of departments reviewed. Observations related to the number of suppliers solicitations were open to and the duration of bid solicitation processes were also noted in several departments. Further, observations related to communications with suppliers and the communication of solicitation results were noted in the majority of departments reviewed.

18. There were several examples noted of insufficient, incomplete and/or inaccurate solicitation documents shared with suppliers. For example, 11% of files reviewed (62 of 540 applicable files) across 12 departments were found to contain incorrect, unclear or missing information or instructions to suppliers. This included instances where solicitation periods or bid enquiry procedures were not established or communicated, and instances where the solicitation document provided inconsistent or contradictory information (e.g., contradictory information regarding security requirements or inconsistent bid submission instructions). A total of 23 files across 9 departments were also found to contain an unclear description of the requirements. This included instances where the description of the requirement included missing or contradictory information or where file documentation did not demonstrate that a clear description of the requirement was provided to invited suppliers. Ensuring completeness and accuracy of information in solicitation documents eliminates ambiguities, contradictions or other discrepancies and helps ensure suppliers have the information they need to prepare and submit responsive bids. This also helps reduce the number of questions from suppliers regarding such discrepancies, and therefore reduces the level of effort required to respond to these questions during the solicitation period.

19. With respect to the openness of solicitations and duration of solicitation periods, OPO found that solicitations were open to an appropriate number of suppliers in 95% of files (514 of 540 applicable files) across 8 departments, and solicitation periods were sufficient in 97% of files (522 of 540 applicable files), also across 8 departments. Cases of non-compliance included, for example, instances where the minimum number of suppliers to be invited in accordance with the professional services method of supply used was not respected, and instances where solicitation periods did not respect minimum lengths established in applicable trade agreements or in the method of supply used.

20. Observations related to communications with suppliers were noted in all but two departments reviewed. This included communications with suppliers during the solicitation period as well the communication of results of solicitation processes. For example, 8% of files reviewed (45 of 540 applicable files) across 15 departments were found to include communication with suppliers during the solicitation period that did not support the preparation of responsive bids. This included instances where responses to bidder questions misrepresented the existence of an incumbent, did not clearly answer the questions posed, or were not shared with all invited suppliers. There were also instances where communications with suppliers occurred by phone or were otherwise not documented and where questions posed were not answered or were answered in close proximity to the bid closing date (e.g., 1 day before the closing date), providing little time for potential bidders to consider the information when preparing their bids. Such actions run counter to the principles of fairness and openness which apply to all aspects of the procurement process, including interactions with suppliers. The record of communications with suppliers was also found to be incomplete in 9% of files reviewed (49 of 540 files) across 8 departments, i.e., missing documentation regarding when questions were asked or by whom, which runs counter to the principle of transparency. Without a complete record of communications, departments cannot demonstrate that all supplier questions were answered in a timely manner, and whether all suppliers were treated equally.

21. The communication of solicitation results (contract award notices and regret letters) was also not in accordance with requirements in 13% of files reviewed (68 of 540 files) across 9 departments. This included instances where contract award notices were not published or not published within the required timelines, or where regret letters were not sent to unsuccessful bidders. In certain instances, the information provided in regret letters was found to be inaccurate or inconsistent with other regret letters providing more detailed information as to why a bid was unsuccessful. Unsuccessful bidders should always be informed of the results of a solicitation process and should be provided an outline of the reasons why their bid was unsuccessful. Regret letters are an essential tool for unsuccessful bidders to understand why they were unsuccessful. It allows them the opportunity to improve for subsequent opportunities and helps them decide whether to pursue debriefings or make use of recourse mechanisms such as OPO or the Canadian International Trade Tribunal. It should be noted that the review performed at Parks Canada (PC) found good practices associated with the contents of regret letters. In addition to providing the name of the winning bidder and value of the contract, PC’s regret letters consistently included, as applicable, the score of the winning bid and the unsuccessful bidder’s score, breakdowns of the unsuccessful bidder’s score, and information on which mandatory criterion or minimum requirement was not met and why, as well as information regarding available recourse mechanisms in more recent regret letters. Detailed regret letters increase the transparency of the procurement process, reduce the need for debriefs in some instances, and may lead to higher-quality future bids on the part of suppliers.

22. Following the receipt of a regret letter, a debriefing can be requested by an unsuccessful bidder in order to obtain additional information as to why their bid was not accepted. Debriefings support the fairness, openness and transparency of the federal procurement process. Explanations provided during the debriefing should help unsuccessful bidders fully understand where their bid fell short, why they were unsuccessful, and where they can improve in subsequent bids. Further, debriefings can also identify opportunities for purchasing departments to improve future solicitation processes.

23. To address identified issues under LOE 2, the Ombud issued recommendations that called for the implementation of measures such as reviewing, updating or establishing internal policies, processes and templates to ensure that relevant and accurate information is shared with suppliers simultaneously, that adequate time is provided for suppliers to prepare and submit bids, that all communications with suppliers are properly documented, and that processes related to the communication of solicitation results are consistently implemented.

LOE 3: To determine whether the evaluation of bids and contract award were conducted in accordance with the solicitation

24. Observations noted under LOE 3 accounted for 35 recommendations (38%), making it the most referenced line of enquiry and also the most concerning. 29% of files reviewed (158 of 540 applicable files) across all 17 departments demonstrated instances where the evaluation process was not consistently applied or was not carried out in accordance with the planned approach. This included deviations such as:

- failing to disqualify bids that did not meet a mandatory requirement

- awarding points not in accordance with established scoring grids

- providing no or insufficient evaluator comments to support evaluations performed

- using an evaluation grid that does not contain evaluation criteria identical to those communicated in the solicitation document

- using a selection methodology that deviated from the one identified in the solicitation document

- erroneously evaluating the financial portion of bids that are technically non-compliant

25. The deviations observed resulted in 6% of files (30 of 540 applicable files) across 13 departments where the contract was wrongly awarded to a non-responsive bidder or to the incorrect responsive bidder. Evaluations not conducted consistently and in the manner prescribed by the solicitation can result in wrongly awarded contracts. Contracts awarded to non-compliant bidders or the incorrect responsive bidder are significant errors that fail to demonstrate good stewardship of Crown resources or that procurements were conducted in a fair, open and transparent manner, and call into question the integrity of the procurement process. Such deviations leave departments unable to explain and defend their decisions and actions and prove that they were made in accordance with applicable laws, regulations and policies. To address these issues, the Ombud issued recommendations that called for measures such as strengthening policies, procedures and guidance as well as implementing appropriate supervision and review mechanisms with respect to evaluation processes.

26. Another significant area of concern across all LOEs and departments relates to documentation, with varying levels of file documentation issues noted in 42% of files (264 of 631 files). File documentation supporting the evaluation process was found to be especially problematic. This included instances where files did not contain any evaluation documentation or did not contain complete individual, consensus or financial evaluations. Other evaluation-related records not always kept on file included evaluation guidelines shared with evaluators, signed evaluator conflict of interest and confidentiality forms, technical and financial bids, and proof that bids were received by the closing date and time specified in the solicitation. Incomplete procurement files result in inadequately supported procurement actions that undermine the transparency of the procurement process. Keeping complete and detailed records is crucial to demonstrating that evaluations have been conducted fairly and consistently. Failure to maintain complete records also places departments at risk of not being able to defend against challenges to the procurement process. To address file documentation issues, the Ombud issued recommendations related to updating or establishing review mechanisms to ensure that procurement files and decisions of business value are appropriately documented.

27. It should be noted that the review performed at Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) concluded that overall file documentation was exceptionally good, with only 3 minor documentation issues that could not be resolved as part of the 40 files reviewed. This review also noted that IRCC had developed and consistently implemented several tools to ensure that procurement files were adequately documented including a planning form, risk assessment tool, evaluation summary report and procurement file checklist.

28. OPO recognizes the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated documentation issues for certain departments that relied on hard-copy record keeping and could not access files due to pandemic-related office closures. The pandemic exposed risks that previously did not exist or were of lesser concern when employees worked in a physical rather than virtual or hybrid environment. One of these risks is linked to a dependence on traditional paper-based procurement processes and contract file retention methods. As such, the pandemic has accelerated the adoption of electronic record keeping.

29. Some PPRs demonstrated a lack of rigor around the procurement process and information management which could be linked to observations where non-contracting professionals (e.g., technical authorities, program managers) were found to be administering the solicitation. This was noted in 10 files in 3 departments where the files contained limited formal documentation that did not support that solicitation processes were conducted in a fair, open or transparent manner. To address these issues, the Ombud issued recommendations with respect to ensuring that officials engaging in the procurement process receive adequate support and training to ensure sound stewardship practices are followed, procurement processes are conducted in a fair, open and transparent manner, and files are adequately documented to support management oversight.

Other Observations

30. In addition to observations made under the 3 standard LOEs presented above, OPO’s PPRs also made additional observations related to files and departmental procurement processes reviewed. Additional observations in 7 departments reviewed led to the issuance of 11 additional recommendations. These recommendations related to topics including:

- Ensuring procurement records are retained in accordance with Treasury Board record-keeping standards;

- Making greater use of technology including allowing for bids to be submitted electronically and alternatives to paper-based methods for managing contract files;

- Establishing processes to review planned procurements to ensure aggregate requirements are not inappropriately divided to avoid controls or trade agreement obligations, i.e., contract splitting;

- Ensuring established procedures with respect to Comprehensive Land Claims Agreement obligations are up-to-date and followed;

- Ensuring established electronic systems accurately track, control and report on contracting activities and ensure all contracts subject to proactive publication are disclosed;

- Ensuring appropriate controls and processes supporting the established procurement governance framework are implemented.

IV. Simplification

31. PPRs are designed and conducted to assess federal procurement activities and make recommendations to promote fairness, openness and transparency. In reviewing the procurement practices of 17 federal departments, OPO sought to draw attention to good practices that simplify the procurement process for bidders and federal officials, as well as identify opportunities for improvement. Some of these good practices and opportunities for improvement are described below.

Standardisation of procurement documents to streamline procurement processes

32. The majority of departments reviewed consistently used standardized procurement documents that reference PSPC’s Standard Acquisition Clauses and Conditions (SACC) manual. This contributes to greater simplification by ensuring consistency and uniformity across procurement processes and helps reduce the burden on suppliers, particularly those who supply the same good or service across multiple departments. Using standardized documents and processes decreases the cost to bid for suppliers and potentially lowers bid prices received by departments.

Limiting the number of technical evaluation criteria

33. Several instances were noted where mandatory criteria included factors that were not essential to fulfilling the requirement, requested documents without assessing the content of those documents (e.g., requesting a resume without assessing its contents), or where the number of mandatory criteria was not commensurate with the complexity of the requirement, calling into question the appropriateness and value of these criteria. Such evaluation criteria are often unnecessary and can make it administratively burdensome for bidders to prepare proposals. Contracting and technical authorities should be cognisant of the possible impacts of excessive or unnecessary criteria on the willingness of suppliers to respond to solicitations, particularly in the case of lower dollar value requirements where the cost to prepare a proposal may exceed the benefits to the supplier of winning the contract. Processes can be simplified by reducing the overall number of technical evaluation criteria and by reducing the number of mandatory criteria to only those elements that are essential to meet the requirement.

34. An example of good practices in the area of simplification was the RCMP. Overall, the files reviewed at the RCMP effectively limited the number of technical evaluation criteria to be in line with the complexity of requirements and for many lower complexity requirements, technical evaluation criteria were avoided altogether. In these cases, the procurement process was simplified as an evaluation solely based on price made it easier for bidders to respond and for evaluators to assess bids.

Use of contract options

35. Several departments including the Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA), Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC), Natural Resources Canada (NRCan), the Correctional Service of Canada (CSC) and the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) made use of contract options to enhance the overall simplification of the procurement process. Including options in contracts, when applicable, supports the simplification of procurement by reducing the number of solicitation processes and, consequently, reduces the cost to both government and suppliers. This practice allows departments to continue working with well-performing suppliers, while being transparent about the amount and value of work associated with a contract during the initial solicitation process.

Simplifying the more common approach to references

36. It has long been common practice to require bidders to provide references as part of their bids. The verification of references however is often not performed as part of the evaluation process. Requesting references places a burden on suppliers as they must ensure that up-to-date reference contact information is provided, and that these references, sometimes going back several years, are available to be contacted by the purchasing department. This increases the level of effort and time required for suppliers to prepare proposals and can add time to the evaluation process. This significant time and effort required by bidders to prepare and provide reference information has the potential of resulting in bidders opting not to participate in competitive processes.

37. When balanced against the fact that in the majority of cases reference information is never sought or utilized by departments, the Ombud recommends that reference information only be sought in exceptional circumstances and not considered a requirement in most solicitations. Departments should consider if there is a less intrusive manner to address the risk that has been identified, such as requiring reference letters, client satisfaction surveys or other alternatives to requesting references.

Efficiency through standardization of simple procurement tools

38. Certain departments have implemented effective tools when planning a procurement to support decisions and facilitate management oversight. For example, the National Research Council (NRC) developed and implemented a Service Contract Information Form as a best practice tool to assist procurement and technical authorities in the planning stages of a procurement. The form captures various details regarding a requirement such as Statement of Work overview, estimated procurement values and dates, security requirements, mandatory PSPC methods of supply, basis of selection, intellectual property considerations, accessibility considerations, etc. When used, contracting authorities will request that technical authorities (i.e., requestors) complete and submit the form before the requirement proceeds to the solicitation stage. The use of such planning tools promotes simplification by reducing the amount of back and forth between contracting and technical authorities when defining requirements and determining procurement strategies. It also supports effective record-keeping and facilitates management oversight by capturing key planning details and decisions.

V. Follow-up reviews

39. Follow-up reviews play an important part in the PPR process by informing interested stakeholders of specific actions departments have taken to improve procurement practices in response to the Ombud’s recommendations. This facilitates other federal departments’ ability to introduce similar improvements, where applicable. Follow-up reviews provide a report card with a rating that depicts OPO’s assessment of the department’s performance with regard to its management action plan to implement the Ombud’s recommendations. This assessment takes into consideration the results from the initial PPR and actions taken by departments to implement the PPR recommendations based on a self-assessment and supporting documentation submitted to OPO. Like PPRs, follow-up reviews are published on the OPO website, at the following link: Progress reports on recommendations—Reports and publications—Office of the Procurement Ombudsman (opo-boa.gc.ca).

VI. Conclusion

40. Over 5 years, the procurement practices of 17 federal departments pertaining to evaluation criteria and selection plans, solicitation, and evaluation of bids and contract award were assessed for consistency with Canada’s obligations under sections of applicable national and international trade agreements, the Financial Administration Act and regulations made under it, the TBCP and departmental guidelines, and to determine if these practices supported the principles of fairness, openness and transparency.

41. Regarding evaluation criteria and selection plans, all departments reviewed were found to include instances of mandatory criteria, point-rated criteria or associated rating scales that were not clearly communicated. Instance of lack of clarity were also observed at times in the majority of departments in the communication of selection methodologies, as well as cases of evaluation criteria not aligning with requirements. Lastly, instances of overly restrictive criteria or criteria that appeared to favour the incumbent or a particular supplier were also observed in the majority of departments.

42. Solicitation documents and organizational practices during the bid solicitation period in most departments were found to include instances of communications with suppliers that did not support the preparation of responsive bids. Inconsistent communications of solicitation results (i.e., contract award notices and regret letters) were also observed. Issues regarding the completeness and accuracy of information in certain solicitation documents were also observed in many departments and, to a lesser extent, certain solicitations were not open to an appropriate number of suppliers or were not open for a sufficient amount of time.

43. Regarding evaluation of bids and contract award, solicitations across all departments reviewed demonstrated instances where the evaluation process was not consistently applied or wasn’t carried out in accordance with the planned approach, including several instances of contracts awarded to non-responsive bidders or to the incorrect responsive bidder, representing the most egregious errors calling into question the integrity of the procurement process. Significant levels of file documentation issues were also observed across all departments reviewed including insufficient evaluation records to demonstrate that evaluations have been conducted fairly and consistently.

44. The reviews performed over 5 years identified instances of procurement practices that were inconsistent with government policy and did not demonstrate that procurements were conducted in a fair, open and transparent manner. Such practices leave departments exposed to the risk of being unable to defend against challenges and jeopardize the integrity of the procurement process. The Ombud issued a total of 92 recommendations to the 17 departments reviewed to address the issues identified.

45. OPO also identified a trend where competitive solicitations reviewed often resulted in only one bid. As competition is mainly how Canada ensures it is receiving a fair price and achieving best value for taxpayers, it is important to understand the main causes of this trend and what can be done to increase competition and support fair, open and transparent procurements. The complexity of the federal procurement process deters many suppliers from bidding on opportunities. Simplifying the process would increase competition by making it easier for new suppliers to do business with the government, and increase efficiency for federal buyers acquiring goods and services.

46. Overall, appropriate internal procurement policies, guidelines and procedures supported by effective training, oversight and quality assurance processes are key to ensuring that government buyers are acquiring goods and services in a fair, open and transparent manner and that a complete audit trail is kept on file to support consistent and transparent decision-making. This is more important than ever as departments have transitioned from policy direction under the TBCP to the DMP. The DMP is notably less prescriptive in its requirements and therefore it is up to departments to develop their own policy instruments that, while aligned with the DMP, are still detailed enough to ensure any file could stand up to the scrutiny of an internal audit. Determining whether a department’s actions support the principles of fairness, openness and transparency in this new policy environment will likely require greater reliance on the role of interpretation, and OPO will look to play a key role in supporting the application of the new obligations across federal departments.

VII. Next steps

47. OPO’s 2018-2023 PPR Plan has helped federal departments better understand the landscape of their competitive procurement activities, including both good practices and areas for improvement. Over the course of the 5-year plan, OPO has noted a variety of trends that have become common throughout the many reviews undertaken. Overall, there is a need for enhanced training and tools and an increased emphasis on governance over procurement activity in terms of both policy instruments and oversight. There are also recurring shortcomings around areas such as the development of evaluation criteria and bid evaluation and contract award. The largest and most consistent issue however involves deficient file documentation practices. These issues have an impact on all areas of procurement and directly impact the principle of fairness and the Government of Canada’s commitment to open and transparent government that is accountable to Canadians in the area of fiscal, financial and corporate transparency.

48. As previously mentioned, the Government of Canada has transitioned from the TBCP to the less-prescriptive DMP which leaves more room for differences in interpretation that could impact departmental action plans and how they are implemented. How departments have implemented the DMP, how they respond to the Ombud’s 92 recommendations, and how they implement changes in their procurement processes and structures are a possible next step for future PPR reviews.

49. Over the last few years, there has also been an increase in requests from the PSPC Minister, members of Parliament and the Standing Committee on Government Operations and Estimates for OPO to perform ad hoc reviews of procurement practices in specific areas (e.g., OPO’s review of non-competitive contracts involving WE charity, and reviews into the awarding of contracts related to the ArriveCAN application contracts awarded to McKinsey & Company, and issues related to the replacement of resources commonly referred to as Bait & Switch). More and more stakeholders are turning to OPO for its expertise in procurement-related matters. To ensure OPO is sufficiently resourced to serve stakeholders and perform both planned and ad hoc systemic reviews going forward, OPO is seeking a permanent budget increase for the first time in its 16 year existence. In the absence of a budget increase, OPO will need to be selective in determining which reviews are undertaken and may need to delay or curtail other activities such as follow-up reviews.

Annex 1—Departments reviewed under the 2018-23 Procurement practice review plan

| Number | Department reviewed | Fiscal Year |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) | 2018-19 |

| 2 | Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) | 2018-19 |

| 3 | Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC) | 2019-20 |

| 4 | Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC) | 2019-20 |

| 5 | Parks Canada (PC) | 2020-21 |

| 6 | Transport Canada (TC) | 2020-21 |

| 7 | Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) | 2020-21 |

| 8 | Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA) | 2020-21 |

| 9 | Natural Resources Canada (NRCan) | 2020-21 |

| 10 | Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) | 2020-21 |

| 11 | Department of National Defence (DND) | 2021-22 |

| 12 | National Research Council of Canada (NRC) | 2021-22 |

| 13 | Correctional Service of Canada (CSC) | 2021-22 |

| 14 | Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada (ISED) | 2021-22 |

| 15 | Public Services and Procurement Canada (PSPC) | 2022-23 |

| 16 | Health Canada—Public Health Agency of Canada (HC-PHAC) | 2022-23 |

| 17 | Shared Services Canada (SSC) | 2022-23 |

Annex 2—Standard review program

Review Objective: The objective of this review is to determine whether organizational processes with respect to evaluation and selection plans, solicitation, and evaluation of bids are consistent with the Financial Administration Act and regulations made under it, applicable sections of the Treasury Board Contracting Policy and support the principles of fairness, openness, and transparency.

| Line of Enquiry (LOE) | Criteria |

|---|---|

| LOE 1: To determine whether evaluation criteria and selection plans are established in accordance with applicable laws, regulations, and policies. | 1.1 Mandatory evaluation criteria are clearly communicated in the solicitation, not unnecessarily restrictive, and are aligned with the requirement. |

| 1.2 Point-rated evaluation criteria and weighting are clearly communicated in the solicitation, not unnecessarily restrictive, and are aligned with the requirement. | |

| 1.3 Selection methodology is clearly communicated in the solicitation document and reflects the complexity of the requirement. | |

| LOE 2: To determine whether solicitation documents and organizational practices during the bid solicitation period are consistent with applicable laws, regulations, and policies. | 2.1 Solicitation is clear and contains complete information and instructions necessary to prepare a compliant bid. |

| 2.2 Design and execution of the solicitation process supports a fair, open, and transparent procurement. | |

| LOE 3: To determine whether the evaluation of bids and contract award are conducted in accordance with the solicitation. | 3.1 A process has been established, complete with guidance for evaluators, to ensure the consistent evaluation of bids. |

| 3.2 The evaluation of bids was carried out in accordance with the planned approach. | |

| 3.3 Adequate documentation exists to support the evaluation of bids and the selection of the successful supplier. |

Annex 3—Establishment of the 5-year Plan and examination methodology

Establishment of the 5-year plan

Year after year, the top issues raised to OPO by stakeholders presented a significant risk to the fairness, openness and transparency of federal government procurement. Figure 3.1 below presents the categories of the top procurement issues raised in the 5 years leading up to the establishment of the 2018-23 PPR Plan:

| Number | 2013-14 | 2014-15 | 2015-16 | 2016-17 | 2017-18 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Evaluation and selection plans | Procurement strategy | Evaluation and selection plans | Bid evaluation and selection plans | Solicitation |

| 2 | Evaluation of bids | Evaluation of bids | Evaluation of bids | Solicitation | Evaluation of bids |

| 3 | Procurement strategy | Evaluation and selection plans | Procurement strategy | Evaluation of bids | Evaluation and selection plans |

| 4 | Debriefings | Security clearance | Payment | Contract execution | Debriefings |

| 5 | Statements of work | Solicitation documents | Statements of work | Statements of work | Statements of work |

By analysing the issues in these categories as well as from various information sources, and by performing a risk assessment to evaluate the risks within each procurement category, OPO developed its standardized 5-year plan (the 2018-23 PPR Plan).

More specifically, OPO’s planning approach included the following:

- Literature review including departmental plans, procurement-related internal audit and evaluation reports conducted by federal departments, and planned external audits by Office of the Comptroller and Office of the Auditor General

- Environmental scanning of various procurement-related information sources

- Data analysis of internal data sources collected by OPO such as supplier contracts, complaints received, comments obtained from suppliers and federal procurement officials during outreach activities

- Evaluation of risks within each procurement category, including identification of controls mitigating these risks, and assessment of the impact of residual risks

Examination methodology

PPRs included review and analysis of documentation such as internal policies, guidelines and directives and review and analysis of a judgemental sample selection of procurement files. Generally, approximately 40 procurement files were selected, with consideration given to factors including materiality and risk. Procurement files selected generally included selections from the highest and lowest valued competitive contracts, high-risk areas as identified by internal data and contract files where the final amended value exceeded the initial contract value by more than 25%. Contract files with no identified issues were also considered, as well as a sample of contracts issued using PSPC established standing offers (SO) and supply arrangements (SA).

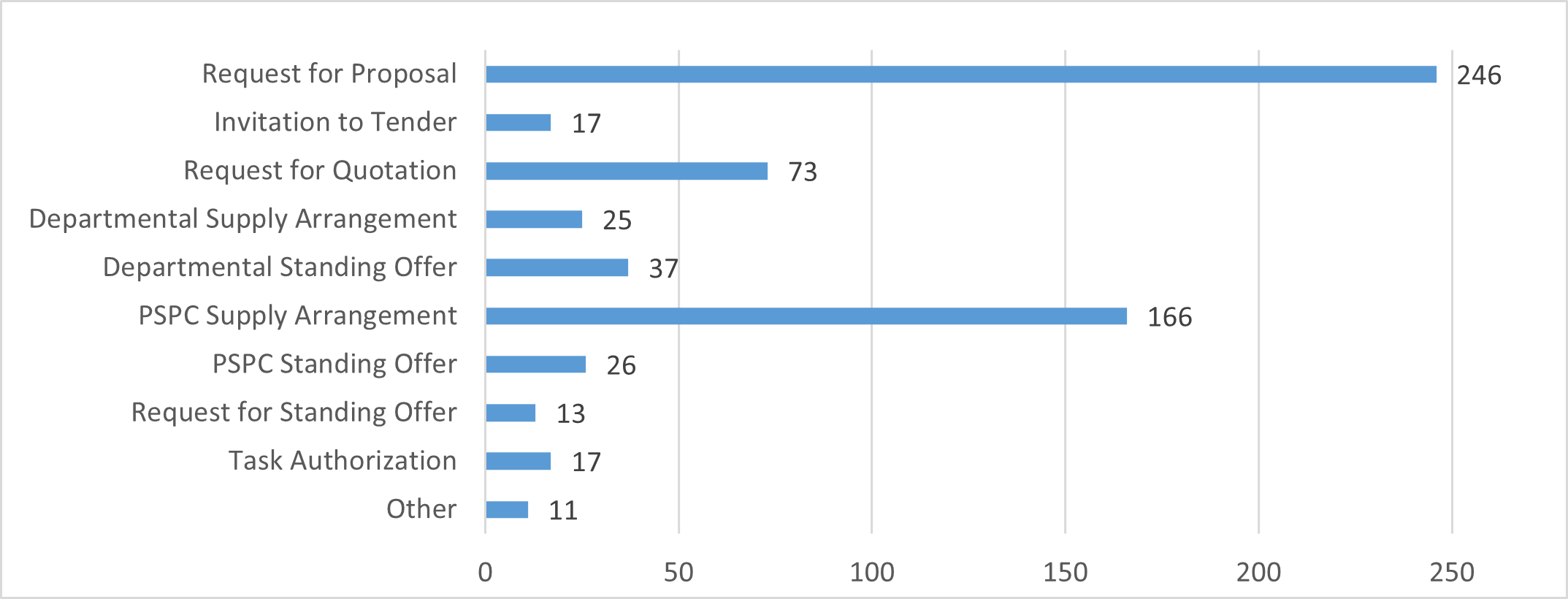

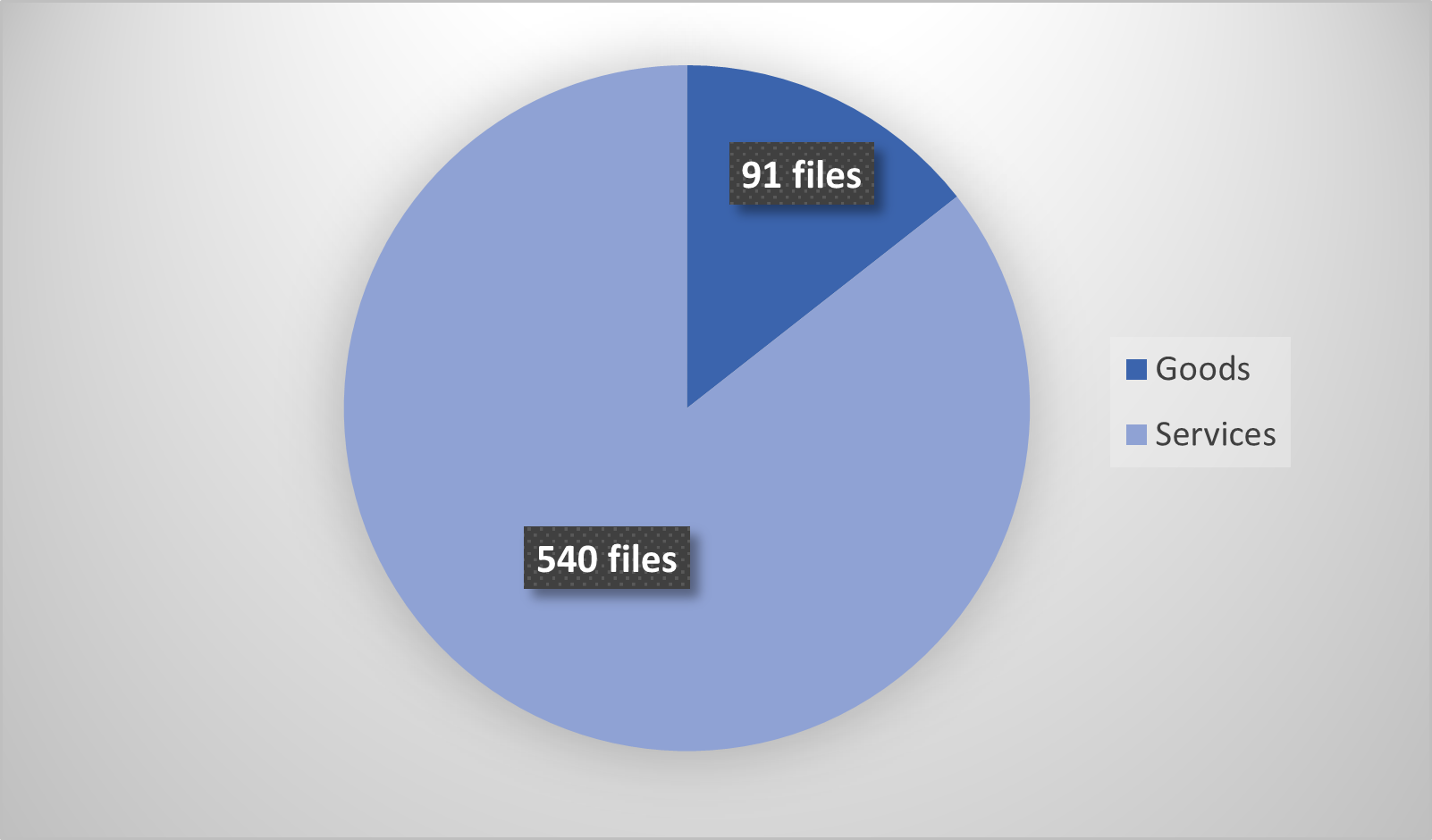

Files reviewed included a variety of solicitation types such as Requests for Proposals, Invitations to Tender, Requests for Quotations, solicitations pursuant to departmental and PSPC SAs, call-ups pursuant to departmental and PSPC SOs, Requests for Standing Offers, and issuance of Task Authorizations with a total of 631 files reviewed across 17 federal departments. Figures 3.2 and 3.3 below provide the breakdown of files by type of solicitation and the breakdown of files by goods versus services.

Figure 3.2: Files reviewed by type

Image description

Breakdown of files reviewed by type:

- Request for Proposal: 246

- Invitation to Tender: 17

- Request for Quotation: 73

- Departmental Supply Arrangement: 25

- Departmental Standing Offer: 37

- PSPC Supply Arrangement: 166

- PSPC Standing Offer: 26

- Request for Standing Offer: 13

- Task Authorization: 17

- Other: 11

Figure 3.3: Files reviewed—goods versus services

Image description

Files reviewed—good versus services

- Goods: 91 files

- Services: 540 files

- Date modified: