Procurement Practice Review of Contracts Awarded to McKinsey & Company

March 2024

On this page

- I. Background

- II. Context

- III. Objective and Scope

- IV. Approach

- V. Policy Overview

- VI. Results

- VII. Conclusion

- VIII. Organizational Responses

- IX. Acknowledgment

- Annex I - Procurement Practice Review of Contracts Awarded to McKinsey & Company

- Appendix A - Treasury Board Questions for Sole-Source Contracts

I. Background

1. On February 3, 2023, the Minister of Public Services and Procurement requested the Procurement Ombud conduct a review looking into contracts awarded to McKinsey & Company (hereafter referred to as McKinsey). On March 16, 2023, after considering available information and determining there were reasonable grounds to do so, the Procurement Ombud launched a review of procurement practices of departments within his mandate for the award of contracts to McKinsey in order to assess their fairness, openness, and transparency and their compliance with legislative, regulatory, policy, and procedural requirements.

2. On January 18, 2023, the House of Commons Standing Committee on Government Operations and Estimates (OGGO) adopted a motion for the Auditor General to conduct “a performance and value for money audit of the contracts awarded to McKinsey & Company since January 1, 2011, by any department, agency or Crown corporation.” The Committee’s motion was accepted by the House of Commons on February 7, 2023.

3. Further, on February 8, 2023, the Office of the Comptroller General of Canada (OCG) directed the Chief Audit Executives of government organizations that had contracted with McKinsey to conduct internal audits of the related procurement processes. The results of these departmental audits were released in March 2023.

4. This procurement practice review of contracts awarded to McKinsey was conducted in accordance with paragraph 22.1(3)(a) of the Department of Public Works and Government Services Act, which gives the Procurement Ombud the authority to review the procurement practices of departments to assess their fairness, openness and transparency, and to make recommendations for the improvement of those practices.

II. Context

5. McKinsey is a management consulting firm that offers professional services to corporations, governments, and other organizations. Based on information provided to the Office of the Procurement Ombud (OPO) departments and agencies subject to the Procurement Ombud’s mandate have awarded contracts to McKinsey with a total value of $117 million from April 1, 2011 to March 31, 2023.

6. Members of Parliament have expressed concerns with Government of Canada contracts with McKinsey. OGGO, whose mandate includes the study of the effectiveness and proper functioning of government operations including both the estimates process and the expenditure plans of central departments and agencies, raised questions related to the use of public funds, transparency, and accountability related to these contracts.

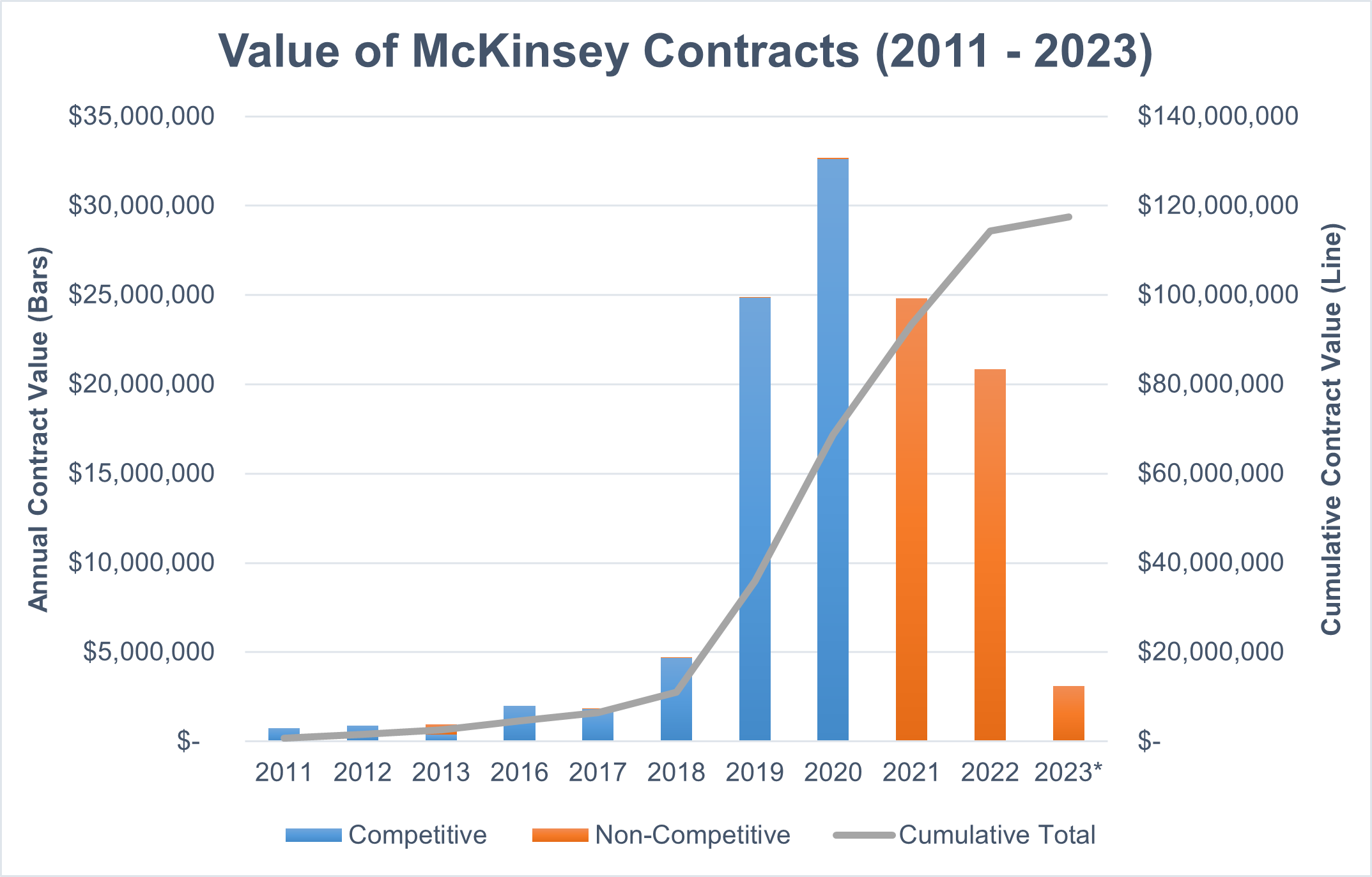

7. The graph below depicts the value of contracts awarded to McKinsey from January 2011 to March 2023 by federal departments subject to the Procurement Ombud’s mandate. As shown in the graph, the value of these contracts was relatively low and consistent between 2011 and 2017. The value of contracts awarded to McKinsey started to increase in 2018 with significant increases observed in 2019 through 2022. The graph also shows from 2011 to 2020, by contract value, the vast majority of McKinsey contracts were awarded competitively. This trend reversed in 2021, from which point McKinsey contracts were predominantly awarded without competition. As will be discussed in this report, a key factor leading to this shift was the establishment of a non-competitive National Master Standing Offer (NMSO) for McKinsey Benchmarking Services.

Value of contracts awarded to McKinsey from 2011 to 2023—Image description

- 2011- 2018- Most contracts were competitive and their total value did not exceed $5M.

- In 2019, the total value of the contracts awarded to McKinsey was nearly $25 million and most contracts resulted from competitive processes.

- In 2020, the total value of the contracts awarded to McKinsey was more than $30M and most contracts resulted from competitive processes.

- In 2021, the total value of the contracts awarded to McKinsey was close to $25 million and most contracts were non-competitive.

- In 2022, the total value of the contracts awarded to McKinsey was just over $20 million and most contracts were non-competitive.

- In 2023, the total value of the contracts awarded to McKinsey was just under $5 million and most contracts were non-competitive.

2023 data is limited to contracts awarded from January to March 2023

III. Objective and Scope

8. This review was undertaken to determine whether procurement practices pertaining to contracts awarded to McKinsey were conducted in a fair, open, and transparent manner. To make this determination, OPO examined whether these practices were consistent with Canada’s obligations under national and international trade agreements, the Financial Administration Act and the regulations made under it, Treasury Board policy and, where applicable, organizational policies and guidelines.

9. The objective of this review was supported by the following four lines of enquiry (LOE):

- LOE 1: Competitive procurement practices leading to contracts awarded to McKinsey

- LOE 2: Non-competitive procurement practices leading to contracts and standing offer agreements awarded or issued to McKinsey

- LOE 3: Practices for issuing contract amendments and task authorizations to McKinsey

- LOE 4: Disclosure of information associated with contracts awarded to McKinsey

10. With certain limitations described below, the scope of this review included all competitive and non-competitive procurement processes and resulting contracts, contract amendments and task authorizations under which work was performed by McKinsey from April 1, 2011 to March 31, 2023. This included procurements conducted by the following departments and agencies as well as those conducted by Public Services and Procurement Canada (PSPC) on behalf of these departments and agencies:

- Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA)

- Department of Finance Canada (FIN)

- National Defence (DND)

- Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC)

- Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC)

- Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada (ISED)

- Natural Resources Canada (NRCan)

- Privy Council Office (PCO)

- Veterans Affairs Canada (VAC)

- PSPC (on behalf of itself)

11. OPO also reviewed contracts awarded by PSPC on behalf of 2 Crown corporations – Export Development Canada (EDC) and Business Development Bank of Canada (BDC). As Crown corporations are not subject to the Procurement Ombud’s mandate, OPO’s review of these procurements was limited to the responsibilities and actions of PSPC as the contracting department.

12. Contracts and acquisition card purchases valued below $10,000 were excluded from this review.

13. OPO originally received 44 files from departments, however, 11 files were removed from the scope of the review:

- 2 files were out of scope as the contract value was below $10,000.

- 5 files (1 each from CBSA, DND, FIN, ISED, NRCan) that were among the oldest in the scope period were outside file documentation retention periods. Consistent with normal information management practices, there was limited documentation available for these contracts.

- 4 files for competitively established supply arrangements for which multiple vendors were qualified. The observations noted under these files did not relate to McKinsey specifically.

IV. Approach

14. OPO’s review consisted of an examination of files for 32 contracts with McKinsey with a total amended value of $112.8 million and 1 National Master Standing Offer (NMSO) issued to McKinsey for benchmarking services. PSPC was the contracting department for 23 contracts and the NMSO, and a total of 9 contracts were awarded to McKinsey by CBSA, DND, ESDC, IRCC, ISED, PCO, NRCan and VAC under their own contracting authorities.

15. Of the 32 contracts reviewed, 7 resulted from competitive procurement processes and 25 were issued through non-competitive procurement processes. Additionally, the Benchmarking Services NMSO was issued to McKinsey through a non-competitive process. Of the 7 competitive contracts, 5 were procured using PSPC methods of supply and 2 were procured through open competition. Of the 25 non-competitive contracts, 19 were contracts (referred to as “call-ups”) issued against the McKinsey Benchmarking Services NMSO and 6 were sole-source contracts awarded without competition based on their low-dollar value.

16. The table below summarizes these 32 contracts:

| Department | Contracts Awarded to McKinsey | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Competitive (7 contracts) |

Non-Competitive (25 contracts) |

Total Number | Total Valuetable 1 note * | |||

| Awarded by Department | Awarded by PSPC | Awarded by Department | Awarded by PSPC | |||

| CBSA | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3 | $5.1M |

| DND | 0 | 0 | 1 | 12 | 13 | $29.1M |

| ESDC | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 4 | $6.6M |

| IRCC | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | $27.7M |

| ISED | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | $3.4M |

| NRCan | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | $25K |

| PCO | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | $25K |

| VAC | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | $25K |

| PSPC | 1 | N/A | 1 | N/A | 2 | $29.6M |

| EDC | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | $7.7M |

| BDC | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | $3.4M |

| Total number | 5 | 2 | 6 | 19 | 32 | N/A |

| Total value | $37.7M | $26.2M | $164K | $48.8M | N/A | $112.8M |

Table 1 Note

|

||||||

V. Policy Overview

17. During the period covered by this review, the Directive on the Management of Procurement replaced the Treasury Board Contracting Policy. In May 2021, the Directive on the Management of Procurement came into effect and departments were given one year to transition from the former Contracting Policy to the new Directive. Since the scope period for this report includes contracts awarded before and after the Directive took effect, this report includes requirements from both the Contracting Policy and the Directive.

18. As stated in the former Treasury Board Contracting Policy, “Government contracting shall be conducted in a manner that will stand the test of public scrutiny in matters of prudence and probity, facilitate access, encourage competition, and reflect fairness in the spending of public funds.” Under the current Directive on the Management of Procurement, the expectation for government procurement to be fair, open and transparent continues as a matter of policy. Expected results of the Directive include “actions related to the management of procurement are fair, open and transparent, and meet public expectations in matters of prudence and probity.”

19. The former Treasury Board Contracting Policy and the current Directive on the Management of Procurement both emphasize the importance of maintaining complete and accurate procurement records. The Policy stated “procurement files shall be established and structured to facilitate management oversight with a complete audit trail that contains contracting details related to relevant communications and decisions…” while the Directive identifies that contracting authorities are responsible for “ensuring that accurate and comprehensive procurement records applicable to the contract file are created and maintained to facilitate management oversight and audit.”

VI. Results

20. Practices pertaining to procurement activities employed by federal departments and agencies when contracting with McKinsey were assessed within the 4 LOEs noted in paragraph 9, above. The Procurement Ombud has made 5 recommendations to address the most serious issues identified in the review that threaten the principles of fairness, openness and transparency. The recommendations, which are summarized in Annex I of this report, are based on the analysis of information and documentation provided to OPO by all departments with contracts awarded to McKinsey during the course of the review.

21. In instances throughout the report, multiple observations may have been made regarding a single file. As a result, the number of observations may not always correspond to the number of files cited.

Line of enquiry 1: Competitive procurement practices leading to contracts awarded to McKinsey

22. There were 7 competitive contracts reviewed under this LOE, which included:

- 5 contracts that were issued under the Task and Solutions Professional Services (TSPS) solution-based supply arrangement

- 1 awarded by CBSA

- 2 awarded by ISED

- 1 awarded by IRCC

- 1 awarded by PSPC on behalf of IRCC

- 1 contract awarded by PSPC on behalf of CBSA that was openly competed

- 1 contract awarded by PSPC on behalf of itself that was competed only amongst suppliers who had qualified under a previous open competitive Invitation to Qualify (ITQ) process

23. TSPS consists of 2 mandatory methods of supply (i.e., supply arrangements), one for task-based requirements and the other for solution-based requirements. Under TSPS, McKinsey was only qualified under the solution-based method of supply. The TSPS solution-based supply arrangement is mandatory for solution-based non-information technology (non-IT) professional services, which covers a wide range of work where “government users are unable to resolve a business problem and require a solution from a supplier as to how to resolve this business problem from start to finish.” Under this method of supply, suppliers are responsible for providing a solution to the business problem in question, managing the overall solution, and accepting responsibility for the outcome.

24. The TSPS solution-based supply arrangement is one of many mandatory PSPC methods of supply for professional services. Others include the TSPS task-based supply arrangement, Task-Based Informatics Professional Services (TBIPS) supply arrangement, and ProServices supply arrangement. To help their clients in their procurement of professional services using these methods of supply, PSPC maintains a centralized web-based portal known as the Centralized Professional Services System (CPSS) e-portal. PSPC has also established rules for the use of these procurement vehicles in the CPSS, for example specifying the minimum number of pre-qualified suppliers that must be invited to bid, how invited suppliers are to be selected, and the minimum period of time invited suppliers are given to submit a bid.

Procurement strategies were changed to allow for McKinsey's participation in procurement processes

25. In general terms, a procurement strategy defines how a good, service, or construction will be procured and takes into consideration the contracting method to be used. Contracting methods include the use of a standing offer, a supply arrangement, a government-wide or multi-departmental contract, or a normal contract. Per the PSPC Supply Manual, the procurement strategy “must satisfy the client's operational requirements and comply with legal requirements, while achieving best value, and advancing national objectives.”

26. Of the 7 competitive contract files reviewed, 2 files showed that the procurement strategy was changed after it was discovered that McKinsey would have been ineligible to bid had the department issued the solicitation under the first method (i.e., supply arrangement) chosen. Without these changes, it would have been impossible for McKinsey to be awarded these 2 contracts.

- For 1 CBSA file for Executive Transformation Services with an amended value of $1,796,700 – during the procurement planning process, the business owner (i.e., CBSA client) asked the CBSA Contracting Authority for a list of qualified suppliers on the supply arrangement they were planning to use. The client later noted that McKinsey was not on the supplier list and the Contracting Authority confirmed that this was because McKinsey was only pre-qualified under the TSPS solution-based supply arrangement – not the task-based supply arrangement. Shortly thereafter, the client notified the Contracting Authority that the Statement of Work (SOW) had been revised as a solution-based requirement rather than a task-based requirement, thereby permitting McKinsey the opportunity to bid. There was no documentation on file to explain why this change was made. The TSPS solution-based supply arrangement was used and McKinsey was selected for contract award as its bid was the only one received and it was deemed compliant.

- For 1 ISED file for International Economic Analysis and Growth Studies with a value of $452,000 – prior to the issuance of a competitive request for proposal (RFP), ISED had considered issuing a contract directly to McKinsey using a process known as an Advance Contract Award Notice (ACAN). As part of ISED’s procurement governance process, the proposed contract was presented to an internal review board where ISED senior management challenged the ACAN approach. As a result, the procurement strategy shifted to a competitive solicitation process. The business owner (i.e., ISED client) and ISED Contracting Authority prepared the documents necessary to issue a competitive RFP to pre-qualified suppliers under the TSPS task-based supply arrangement. ISED contacted McKinsey to confirm which resource categories they were qualified under and provided them with a link to the TSPS task-based supply arrangement streams and categories listing for reference. In response, McKinsey confirmed that they were pre-qualified under the TSPS solution-based supply arrangement, but – not the task-based supply arrangement. Shortly thereafter, the client asked the Contracting Authority for assistance in “revising the evaluation grid given that McKinsey is registered on the TSPS Solutions-based Supply Arrangement…”. The RFP was then issued under the TSPS solution-based supply arrangement. Three bids were received and following the evaluation process, McKinsey was selected for contract award as its bid was the only one deemed compliant.

27. There can be legitimate reasons for changing a procurement strategy. For example, for the ISED contract cited above, the strategy initially changed from a non-competitive ACAN to a competitive process, thereby enhancing transparency and openness. More generally, a contracting authority may advise their client that the nature of the requirement is better suited for one procurement tool over another, leading to a change in the procurement strategy. However, in these CBSA and ISED procurements, after identifying a task-based approach as appropriate, the requirement was changed to accommodate a solution-based approach upon learning that McKinsey would not be eligible to participate in the procurement process. The difference between these two methods is significant. Each method covers a different scope of work and requires a different means of delivery. Task-based requirements are finite work assignments, with specific start and end dates and set deliverables. In contrast, solution-based requirements are not related to specific tasks. They are used when a department is unable to resolve a business problem and requires a solution from a supplier as to how to resolve the business problem from start to finish. Given these circumstances combined with the absence of any documentation on file to otherwise support the legitimacy of this decision, the efforts on the part of CBSA and ISED to ensure McKinsey could participate create a strong perception of favoritism. Though these procurements ultimately “fit” within the TSPS solution-based supply arrangement, these examples demonstrate the importance of robust controls and oversight of procurement as a process may appear to follow the applicable rules but not result in a process that was fair, open and transparent.

Recommendation 1:

CBSA and ISED should implement procedural controls to ensure procurement strategies are centered on satisfying operational requirements rather than engaging specific suppliers.

Centralized Professional Services System e-portal search results

28. When using the TSPS method of supply, the Contracting Authority is required to conduct an initial CPSS search using criteria based on the operational requirement (e.g., resource categories and security requirements) to identify a pool of potential suppliers that are qualified under the method. For procurements valued at $100,000 up to $3,750,000, a second CPSS search is conducted to identify specific suppliers (minimum 15 is standard) that will be invited to bid. Contracting Authorities must retain records of searches conducted to demonstrate that CPSS e-portal common business rules have been applied.

29. A CPSS search was required for the 5 contracts that were issued under the TSPS solution-based supply arrangement. For 4 of the 5 contracts, file documentation demonstrated that the CPSS search results had been properly retained in the file.

30. However, for 1 contract where the procurement was conducted by CBSA, CPSS search results were missing from the file. Per the requirements of the supply arrangement, the solicitation was to be issued to 15 TSPS supply arrangement holders. However, since there were no CPSS search results retained, it was not possible to confirm whether the 15 invited suppliers were qualified to bid.

31. The consequence of not documenting CPSS search results is that Contracting Authorities cannot demonstrate that invited suppliers were qualified supply arrangement holders at the time of solicitation or that they were appropriately selected in accordance with CPSS rules.

Evaluation of bids and contract award

32. In order to ensure the fairness and defensibility of evaluation processes, both the former Treasury Board Contracting Policy and the current Directive on the Management of Procurement require due diligence in the evaluation of bids. This includes strict adherence to evaluation criteria and equal application of criteria for all bidders. When proposals are evaluated in a consistent manner, the selection process will result in the award of the contract to the most suitable bidder and maintain the integrity of the procurement process. The Directive also underscores the importance of proper documentation by stating Contracting Authorities are responsible for ensuring that accurate and comprehensive procurement records are created and maintained on the contract file to facilitate management oversight and audit, including but not limited to individual assessments, consensus evaluations, relevant decisions, approvals, communications, and dates.

Bid evaluation records

33. Bid responses from all suppliers must be maintained on the contract file by either the Contracting Authority or the business owner (i.e., client) or a combination of the two. Responses from suppliers should include all required elements as specified in the bid solicitation (e.g., technical bid, financial bid, and certifications) that will allow for the evaluation of each accepted proposal against all evaluation requirements.

34. For the 7 competitive contracts reviewed, OPO reviewed the client department files and PSPC contract files, when applicable, to assess the completeness of documentation to support and demonstrate fairness in the evaluation of bids.

- In 4 files awarded by ISED (2), and PSPC (2) (1 on behalf of IRCC and 1 on behalf of itself), conflict of interest declarations completed by the individuals who performed the technical evaluation of bids were not present. Conflict of interest declarations are an important tool to protect the integrity of the evaluation process and represent a tangible record that evaluators were informed of and acknowledged their duties and obligations with respect to potential conflicts of interest that may arise in the course of the bid evaluation process.

- In 3 files awarded by ISED (2) and PSPC on its own behalf (1), evaluation documentation was lacking signatures and/or dates.

- In 3 files awarded by CBSA (1), ISED (1) and PSPC on behalf of IRCC (1), records of the evaluation of bids were deficient as documentation regarding individual and consensus bid evaluations were incomplete or absent from the file. When present and appropriately documented, evaluators’ worksheets are an integral part of the evaluation process as they constitute part of the complete record, form the basis for debriefing unsuccessful bidders and provide justification for evaluation results.

35. The following are descriptions of what OPO observed with respect to the 3 files with deficient records of evaluations:

- For 1 CBSA file for Executive Transformation Services with an amended value of $1,796,000 – CBSA awarded a contract to McKinsey under the TSPS solution-based supply arrangement. McKinsey’s bid was the only bid received. The file contained no documentation for the individual or consensus evaluations.

- For 1 IRCC file for Transformation Services with an amended value of $24,848,700 – PSPC awarded a contract to McKinsey on behalf of IRCC under the TSPS solution-based supply arrangement. McKinsey’s bid was the only bid received. The file contained only one individual evaluation (there were 3 evaluators), no documentation for the consensus (i.e., final) evaluation and no signed conflict of interest forms from evaluators.

- For 1 ISED file for Global Analysis of Economic Stabilization and Recovery in High Growth Sectors with an amended value of $2,988,497 – ISED awarded a contract to McKinsey under the TSPS solution-based supply arrangement. Two bids were received. The file contained ambiguous and incomplete evaluation documentation. For example, there were several different evaluation documents on file, with no clarity as to which was considered for determining the award of the contract. There were two documents on file referred to as "consensus evaluation form" and "consensus evaluation form – McKinsey;" however, both of these documents were unsigned. The "consensus evaluation form - McKinsey" document only included an assessment for one of the mandatory criteria and left the other criteria unassessed. Additionally, OPO noted there were no conflict of interest forms from evaluators on file.

36. The general deficiency of documentation observed is an ongoing area of concern for OPO that extends beyond the parameters of this review. OPO has identified this same issue in numerous procurement practice reviews conducted over the past few years involving more than a dozen departments and agencies. While some of the contracts reviewed were entered into during the COVID-19 pandemic when there was a rapid shift from the use of paper-based to electronic procurement records, this does not explain the constant occurrence of this issue across multiple departments and time ranges. Without documentation to support contract award decisions, departments cannot demonstrate that the contracting process was compliant with applicable legislation and policy.

Contract award decisions and resulting contracts

37. When evaluation documentation was included in the procurement file, there were several instances where evaluations were not done as per the planned approach, jeopardizing the integrity of the procurement process. OPO reviewed the 7 competitive contract files to assess how compliant bids were ranked and whether the selection methodology, as stated in the bid solicitation document, was applied correctly.

38. OPO’s observations included instances of: evaluations not demonstrating that bids were evaluated against all criteria in the solicitation (1 contract); deviations in the evaluation process (1 contract); and consensus evaluations not appropriately documenting the rationale for points assigned (2 contracts). Below are descriptions of these observations:

- For 1 IRCC file for a Service Transformation Strategy with an amended value of $2,890,822 – the evaluation did not demonstrate that all bids were evaluated against all mandatory criteria in the solicitation. One of the mandatory criteria stated “The Bidder must propose a team of resources” and that “all proposed resources must meet the minimum score of the flexible grid under TSPS for their respective levels of expertise and categories.”Footnote 1 However, there was no evidence on file to demonstrate that proposed resources were assessed against the TSPS flexible grids during the evaluation of bids. While the consensus evaluation document included comments stating the flexible grid minimum scores were met, there was no record of the assessment of the flexible grids on file to support this conclusion.

- For 1 ISED file for Global Analysis of Economic Stabilization and Recovery in High Growth Sectors with an amended value of $2,988,497 – deviations to normal procedures were observed in the bid evaluation process.Footnote 2 In this case, 2 bids had been received and both were deemed compliant following the technical evaluation. The Contracting Authority then conducted the financial evaluation and determined the lower ranked technical bid was ranked 1st overall based on its lower price and superior financial score. However, after the results were shared with the bid evaluation team, the business owner expressed concern that the evaluation team may have overlooked something in the mandatory criteria and wanted to re-evaluate the 1st overall ranked bid. The Contracting Authority advised that this would not be possible given the fact that the financial evaluation had been completed. The response from the business owner stated he would be “happy to delete the financial evaluation email.” The deletion of records in the manner suggested would raise significant concerns about the fairness of the process. ISED ultimately did revise its evaluation of the 1st ranked bidder and deemed it non-compliant for not meeting all mandatory criteria. McKinsey was then awarded the contract as the only compliant bidder. While some aspects of this procurement process were well documented, there was a significant shortcoming with respect to documentation of the decision to allow the evaluators to change their evaluation of the 1st ranked bid after they learned the results of the process. The actions taken in this evaluation process lead OPO to conclude that this contract was not awarded in a fair and transparent manner.

- For 1 PSPC file for Accelerator Services to Support the Public Service Pay Centre with an amended value of $29,620,266 and 1 ISED file for International Economic Analysis and Growth Studies with a value of $452,000 – the consensus evaluations did not appropriately document the rationale for points assigned to point rated criteria. In both cases, points were deducted from bidders without a documented rationale for these decisions.

- For the same PSPC file noted immediately above – a bid was incorrectly deemed responsive, however, it did not affect the outcome of the procurement. The solicitation was a competitive RFP that was preceded by an Invitation to Qualify (ITQ).Footnote 3 At the ITQ stage, OPO observed that one of the bidders (not McKinsey) was identified as non-responsive to a mandatory requirement based on the results of the consensus evaluation. However, this supplier was advised that their bid was deemed responsive and it was one of the two suppliers invited to submit a bid for the subsequent RFP (the other being McKinsey). Once evaluated at the RFP stage the supplier was deemed non-compliant for the same reasons it was identified as being non-compliant during the consensus evaluation at the ITQ stage. The supplier may have unnecessarily incurred costs related to the preparation of their bid since it appears unlikely that they had a chance of being deemed compliant at the RFP stage.

39. It is important for evaluators to demonstrate that they have considered all aspects of a bidder’s proposal and have assessed all bids fairly against the criteria. Deviations from established evaluation processes threaten the fairness of a competitive procurement process and should be avoided.

Security clearances

40. OPO reviewed contract files to verify that security requirements identified in the solicitation had been confirmed with appropriate documentation on the file. As part of this review, OPO reviewed file documentation for evidence that personnel security requirements, e.g., Secret or Reliability status, were verified before proposed resources were authorized to work on the contract in question. Secret clearance is required by a resource working on a sensitive government contract to access Secret information and assets. Reliability status is required by a resource working on a sensitive government contract to access information and assets up to the Protected B level.Footnote 4 As well, OPO reviewed files to confirm that contractual documents were sent to PSPC’s Contract Security Program (CSP), when applicable.

Validation of resource security clearances

41. Of the 7 competitive contracts reviewed, 6 had personnel security requirements. For those 6 contracts, there were 2 files with missing documentation or insufficient documentation to confirm the validity of the required personnel security clearances at the level of Reliability status. These included 1 contract awarded by ISED and 1 contract awarded by PSPC on behalf of itself.

42. For the contract awarded by ISED, the file did not include confirmation of security clearance information for the 7 resources included in McKinsey’s bid.

43. For the contract awarded by PSPC on behalf of itself, resources were added through task authorizations that were issued after contract award. As such, security clearances were to be validated at the time of the task authorization. PSPC documentation confirmed that 4 of the 5 resources added through task authorization had the appropriate security clearance. The 1 remaining resource did not have the required Reliability status security clearance; nonetheless, this individual was included on the approved task authorization. PSPC informed OPO that a security clearance request had been initiated but it was never completed.

44. In absence of documented confirmations of personnel security requirements, resources may have worked on these contracts and had access to sensitive information and assets without having the required security level.

Verification of contract sent to PSPC’s Contract Security Program

45. All government departments that award contracts with security requirements under their respective delegated contract authority and who used the PSPC Contract Security Program’s contract security services must send a copy of their contract to the Contract Security Program, including copies of any subsequent contract amendments. This would apply, for example, when a contract with a security requirement was awarded under a PSPC method of supply. This is done to ensure the integrity of the contract security process, as well as the timely and efficient delivery of security screening services to suppliers, their personnel and their subcontractors.

46. Of the 6 competitive contracts with security clauses, 2 files, including 1 contract awarded by PSPC on behalf of CBSA, and 1 contract awarded by PSPC on behalf of itself, included evidence that a copy of the contract had been provided to the CSP. For the remaining 4 contracts, the file did not have a record (i.e., email) showing that the contract with a PSPC security clause had been provided to the CSP. These 4 contracts were awarded by CBSA, ISED, IRCC, and PSPC on behalf of IRCC. In response to OPO’s observation, PSPC confirmed with the CSP the submission status of these 4 contracts. PSPC confirmed the contract awarded by PSPC on behalf of IRCC had been provided to the CSP, however, the CSP did not have any records for the remaining 3 contracts that had been awarded by CBSA, ISED and IRCC.

Recommendation 2:

PSPC and ISED should not authorize any work without first confirming that all resources named in the contract and all resources added through task authorizations meet all security requirements, and should retain the confirmation in the contract file.

Line of enquiry 2: Non-competitive procurement practices leading to contracts and standing offer agreements awarded or issued to McKinsey

47. Under LOE 2, OPO reviewed non-competitive award processes of contracts and a contract instrument that was not immediately preceded by a competitive process. In total, this comprised 26 files, which included:

- 6 files for low dollar value sole-source contracts

- 1 file for the establishment of a National Master Standing Offer (NMSO) for McKinsey Benchmarking Services

- 19 files for non-competitive contracts (i.e., call-ups) issued against the McKinsey Benchmarking Services NMSO

48. The 6 low dollar value sole-source contracts were awarded by DND, ESDC, NRCan, VAC, PCO, and PSPC (on behalf of itself). PSPC also established the McKinsey Benchmarking Services NMSO and issued all 19 call-ups against that instrument. While authorized users of the McKinsey Benchmarking Services NMSO were permitted to issue call-ups valued below $200,000, all of the call-ups issued exceeded this amount. As a result, PSPC functioned as the contracting department for all call-ups, including:

- 1 on behalf of CBSA

- 12 on behalf of DND

- 3 on behalf of ESDC

- 1 on behalf of BDC

- 2 on behalf of EDC

49. The Government Contracts Regulations (GCR) have the force of law and establish the requirements that federal departments must respect when contracting for goods, services and construction. The GCR underline the predominance of competitive procurement by requiring contracting authorities to solicit bids before awarding contracts. That said, section 6 of the GCR provides several exceptions to the general rule requiring competition.

50. Of note, these exceptions allow for non-competitive contracting where the estimated expenditure (i.e., cost) does not exceed certain dollar thresholds (GCR section 6(b)):

- Prior to June 10, 2019 the threshold was $25,000 for goods and most services contracts

- Since June 10, 2019 the thresholds are $25,000 for goods contracts and $40,000 for most services contracts

51. Further, section 6 of the GCR provides for an exception when only one supplier is capable of performing the work (GCR section 6(d)). With respect to these situations, the Treasury Board Secretariat requires departments to respond to a set of questions, commonly referred to as the Treasury Board (TB) 7 questions, to explain and justify why exception 6(d) of the GCR has been invoked to allow a sole-source contract. The TB 7 questions are presented at Appendix A of this report for additional context.

Sole-source contracts

52. The 6 low dollar value sole-source contracts were awarded to McKinsey by federal departments between November 9, 2017 and August 3, 2020. For these contracts, the estimated cost for each did not exceed the $25,000 or $40,000 threshold that was in effect at the time of the procurement. For this reason, the use of non-competitive processes for awarding these contracts was consistent with the low dollar value exception to the GCR requirement to solicit bids.

Establishment of estimated cost

53. The GCR do not state at what point during the procurement process cost estimates need to be established; however, the Treasury Board Contracting Policy did stipulate when this should occur. Section 10.5.1 of the Policy stated in part, “requirements should be defined and specifications and estimates established before bids are solicited and contracts let, so that all prospective contractors are treated equally.”

54. Files for 2 of the 6 low dollar value sole-source contracts, awarded by NRCan and PSPC on behalf of itself, included appropriately documented estimates. In the other 4 files, for contracts awarded by VAC, DND, ESDC and PCO, the documentation did not clearly show that an estimated cost was established before the department contacted McKinsey about its requirement.

55. The estimated cost of 2 of these contracts was significantly below the threshold amount specified in section 6(b) of the GCR, at the time of the procurement.

- For the VAC file for Business Consultant/Change Management Consultant services valued at $24,860 – VAC contracted this requirement on behalf of the Office of the Veterans Ombud (OVO). The earliest reference on file by the OVO regarding the estimated cost of $25,000 was during email communications between the OVO and McKinsey discussing the requirement. The threshold limit at the time of the procurement was $40,000.

- For the DND file for the Royal Canadian Navy (RCN) Digital Use Case Workshop valued at $24,860 – the earliest reference by DND on file regarding the estimated cost of less than $25,000 was in an e-mail communication between the business owner and DND procurement. Prior discussions between the business owner and McKinsey had taken place regarding this requirement. The threshold limit at the time of the procurement was $40,000.

56. The estimated cost of the remaining 2 contracts was absent or was just below the $25,000 or $40,000 GCR threshold for non-competitive contracting in effect at the time of the procurement.

- For the ESDC file for Advisory Services to the Chief Operating Officer valued at $40,000 – there was no estimated cost identified on the file. The threshold limit at the time of the procurement was $40,000.

- For the PCO file for Planning and Presentation Services on Disruptive Technologies valued at $24,747 – it appeared the estimated cost of $24,747 (including tax) was established after the quote was received from McKinsey. The threshold limit at the time of the procurement was $25,000.

57. This result is not unique to contracting practices with McKinsey and was identified by OPO in a previous procurement practice review looking at low dollar value contracts. Directly contacting a prospective supplier, sharing information about an upcoming requirement with that supplier, and requesting pricing information from that supplier before establishing and documenting the estimated cost of a contract represents a threat to the fairness of the procurement process and should not be repeated. In the event the supplier’s proposed price exceeds the threshold for non-competitive contracts set forth in the GCR, the department may be required to run a competitive process before awarding the contract. In this situation, not all prospective suppliers would be treated equally, as the supplier that was previously contacted for pricing information would have an unfair advantage over other potential suppliers because it received information about the requirement before anyone else. Alternatively, the department may decide to remove some of the goods or services it required to get the estimated cost below the threshold amount primarily for the purpose of avoiding competition or targeting a particular supplier. This action could be perceived as a manipulation of the exception to competition permitted by the GCR.

58. The practice of directly contacting a prospective supplier to request pricing information prior to establishing and documenting the estimated price of a contract should be avoided to ensure the fairness of the procurement process. However, if information is required from suppliers to assist with program planning or for budgetary purposes, a formal pre-solicitation process, such as a Price and Availability (P&A) enquiry or a Request for Information, should be issued so that all potential suppliers are given information about the requirement at the same time and have the opportunity to respond.

Justification for not using a mandatory method of supply & changes to the procurement strategy

59. PSPC has established standing offers and supply arrangements to enable federal departments to award contracts to pre-qualified suppliers using a streamlined process. The use of standing offers and supply arrangements is mandatory for certain commodity groups listed in the former Treasury Board Contracting Policy and in the current Directive on the Management of Procurement. When considering a new contract, departments must verify whether a mandatory standing offer or supply arrangement exists that meets their requirements. If one does, the contracting department must use it. Exemptions to this rule are possible, but must be obtained from PSPC prior to proceeding with the procurement. If an exemption is not granted, the client department may proceed under their own authority and in so doing, assume any associated risks with this business decision. This decision must be recorded on the contract file.

60. For 4 of the 6 sole-source contracts reviewed, the task-based services acquired fell within a commodity class for which the use of the PSPC ProServices supply arrangement was mandatory. However, rather than using this method of supply to select a pre-qualified supplier to provide the required services, contracts were awarded by ESDC, PCO, NRCan and DND to McKinsey through non-competitive processes. In all of these cases, the required exemptions were not sought and obtained from PSPC. It was also noted that at the time of these procurements, McKinsey was not a qualified supplier under ProServices and had this method of supply been used, McKinsey would not have been eligible to be awarded these contracts.

61. Furthermore, in 3 of the 6 sole-source contracts reviewed, there was evidence that the procurement strategy was changed to allow for McKinsey’s participation.

- For the ESDC file for Advisory Services to the Chief Operating Officer with a value of $40,000 – the use of ProServices was considered and acknowledged by ESDC to be the appropriate method of supply for the services sought. However, ESDC noted that McKinsey was not a qualified supplier under ProServices and instead directed the contract to McKinsey outside the ProServices method of supply.

- For the VAC file for Business Consultant/Change Management Consultant services valued at $24,860 – the use of ProServices was acknowledged by VAC to be the appropriate method of supply for the services sought. The VAC Contracting Authority discovered that McKinsey was not a qualified supplier under ProServices but was qualified under the TSPS solution-based supply arrangement and sought the guidance of the PSPC TSPS group to confirm if they could still contract with McKinsey. The PSPC TSPS group advised that VAC would need to stay within the list of vendors for each supply arrangement but could use the TSPS solution-based supply arrangement if their requirement was seeking a solution. Following this, the SOW was re-written from a task-based requirement (i.e., subject to ProServices) to a solution-based requirement and VAC directed the contract to McKinsey under the TSPS solution-based supply arrangement.

- For the PSPC file for an Independent Review of HR-To-Pay valued at $24,860 – the requisition that was sent to the PSPC procurement group made specific reference to the use of the ProServices supply arrangement. Along with the requisition was an attached file named “Statement of Work – McKinsey – 2019-05-02”. McKinsey, however, was not pre-qualified under the ProServices supply arrangement and would have been ineligible for contract award if the ProServices method of supply was used. The contract was ultimately awarded under the TSPS solution-based supply arrangement under which McKinsey was a qualified supplier. There was no documentation on file detailing the reasoning for the use of the TSPS solution-based supply arrangement rather than ProServices. In response to OPO’s observation, PSPC stated that upon their review of the statement of work, the use of TSPS was justified for this requirement and speculated that this may have been the reason for changing the method of supply. However, without documentation on file, the perception remains that this decision may have been motivated by the fact that McKinsey was not a qualified supplier under ProServices.

62. These actions run counter to the principles of fairness and openness in government contracting by removing a potential contracting opportunity from pre-qualified suppliers that had been identified through an open process advertised on the Government Electronic Tendering System without proper justification for doing so. In cases where the use of mandatory methods of supply were avoided altogether, it potentially resulted in the department paying more for the services due to the lack of competitive influence on the price charged.

Recommendation 3:

ESDC, PCO, NRCan and DND should implement procedural controls to ensure mandatory methods of supply are utilized when required and exemptions from PSPC are sought and documented, when applicable.

Verification of resource security clearances

63. As was done for competitive contracts reviewed under LOE 1, OPO reviewed the 6 low dollar value sole-source contract files to verify that security requirements, when applicable, had been confirmed with appropriate documentation on the file. Of the 6 files reviewed, 2 had security requirements, including 1 contract awarded by ESDC and 1 contract awarded by PSPC on behalf of itself. While the ESDC contract file contained appropriate documentation to demonstrate the security requirement had been met, the PSPC contract file did not have evidence confirming the validity of the resource’s required Reliability status security clearance.

Establishment of the McKinsey Benchmarking Services National Master Standing Offer

What is a standing offer

64. A standing offer is a non-binding agreement between the federal government and qualified suppliers for the provision of specific goods or services under pre-established terms and conditions, including price. Under a standing offer the price and terms of the contract are pre-defined and agreed upon, allowing for more timely contract award. When a need is identified, the organization issues a contract, known as a “call-up”, against the standing offer, which creates the contract with the supplier. Procuring authorities are required to buy certain commodities, including professional, administrative and management support services, using mandatory standing offers and supply arrangements established by PSPC.

65. Standing offers are well-suited to deliver goods and services that can be precisely defined and accurately costed in advance. While minor customizations to the goods or services may occur in the negotiation of the call-up, substantial or material deviations from the good or service originally defined in the standing offer are not permitted. Identifying the appropriate standing offer that accurately represents a department’s operational requirement is paramount to the effective use of such tools and upholding the integrity of the process used to establish the standing offer.

66. There are several types of standing offers issued by PSPC. The appropriate standing offer type used depends on the geographical area and number of federal departments or agencies involved. A National Master Standing Offer (NMSO) is a type of standing offer which is used by many departments or agencies throughout Canada. A standing offer may be issued, as a result of a competitive solicitation, to one or more suppliers for the same good or service, in accordance with the bid evaluation and selection methodology. A standing offer may also be directed on a non-competitive basis to one supplier for goods or services, as was the case with the McKinsey Benchmarking Services NMSO.

Background on the McKinsey Benchmarking Services National Master Standing Offer

67. On February 26, 2021, PSPC issued an NMSO for benchmarking services to McKinsey following a non-competitive process. The McKinsey Benchmarking Services NMSO was established to provide departments and agencies with “benchmarking services which consist of functional tools, databases, and expert support to measure their performance against similar Canadian and international organizations, in order to identify deficiencies and opportunities for improvement.” The scope of the NMSO consisted of one or more benchmarking solutions (i.e., tools and databases) in addition to expert support services to report on the recommendations for proposed mitigation strategies identified. The initial period of the NMSO was from March 1, 2021 to February 28, 2022 and included an option to extend for an additional one-year period. This option was exercised and the NMSO was extended to February 28, 2023. The McKinsey Benchmarking Services NMSO has now expired and has not been replaced.

68. PSPC had previously issued 3 other non-competitive NMSOs with other vendors for benchmarking services and shortly after the establishment of the McKinsey Benchmarking Services NMSO, a fifth was issued. Only one of these 5 NMSO’s remains in effect and it is set to expire in June 2024. According to PSPC, the McKinsey Benchmarking Services NMSO was established to provide federal departments and agencies (i.e., client departments) with additional options for obtaining these types of services. The NMSOs for benchmarking services issued to the 4 other vendors were not included in the scope of this review.

69. The call-up limitation for authorized users of the McKinsey Benchmarking Services NMSO was $200,000 (including taxes); call-ups exceeding this amount had to be issued by PSPC. During the period of the McKinsey Benchmarking Services NMSO, PSPC’s contracting authority for non-competitive service contracts was (and continues to be) $5.75M. Call-ups with values exceeding this amount would have required Treasury Board approval. To initiate a call-up requiring PSPC’s contracting authority, the client department had to provide PSPC with 3 items: 1) a 9200 (requisition) form; 2) the quotation or proposal from the Offeror (i.e., McKinsey); and 3) a Security Requirements Checklist (SRCL). A SOW developed by the client department specific to the requirement of the call-up was not identified as a requirement of the call-up procedures.

Public Services and Procurement Canada’s documentation does not provide required justification for non-competitive procurement strategy

70. Openness in federal government contracting is a fundamental principle and because of this, competition is the norm. This default position is set out in section 5 of the GCR which stipulates that normally, before a contract is awarded, bids must be solicited. However, as previously mentioned, section 6 of the GCR sets out 4 exceptions to competitive contracting. The GCR exception PSPC invoked in the establishment of the McKinsey Benchmarking Services NMSO was 6(d) (“only one person is capable of performing the contract”).

71. When a non-competitive procurement strategy is chosen, departments must record the full justification for the GCR exception cited with appropriate documentation placed on the contract file, and if applicable, the justification for the utilization of the limited tendering reason of the applicable trade agreements. In cases where the GCR exception 6(d) is invoked, departments must also document their responses to 7 questions required by Treasury Board Secretariat (a.k.a. TB 7 questions) to justify their rationale. These documented justifications are critical to ensure the department can demonstrate that the tenets of fairness, openness and transparency in the procurement process have been considered and respected.

72. As PSPC invoked GCR exception 6(d) when establishing the McKinsey Benchmarking Services NMSO, and cited the limited tendering reason as that of McKinsey’s exclusive rights, PSPC was required to demonstrate and document on the file both that: 1) exclusive rights exist; and 2) no reasonable alternatives or substitutes exist that can achieve the desired outcomes.

73. With respect to the first element of the existence of McKinsey’s exclusive rights, PSPC’s response to the TB 7 questions addressed this by stating “The Offeror has the exclusive ownership [of] the datasets and analytics used in its solutions (benchmarking services). These data sets are based on information obtained from McKinsey’s clients through proprietary surveys… No other vendor has the right to use McKinsey’s datasets, nor are resellers authorized to distribute McKinsey surveys or apply its diagnostics.” OPO does not contest this assertion by PSPC that McKinsey held exclusive rights to the benchmarking solutions offered.

74. The existence of exclusive rights alone does not automatically justify a non-competitive contracting process. To do so, departments must demonstrate that there are no alternative solutions available that would accomplish their objectives, aside from the goods or services protected by exclusive rights. To meet this requirement, a department must first identify their required outcome. This outcome must be developed using goal-oriented criteria, rather than product-specific and focusing on a particular tool. Then the department must satisfy itself that such an outcome may not be achieved through an alternative solution without violating the exclusive rights.

75. With respect to the second element of whether a reasonable alternative or substitute exists, OPO finds that PSPC’s documented justification for the sole-sourced NMSO did not demonstrate that there was no alternative to McKinsey’s exclusive datasets and analytics that could meet their objectives.

76. When responding to the TB 7 questions document, which asked if there were alternative sources of supply for the same or equivalent service, PSPC answered “No, there are no alternative sources of supply offering the same or equivalent services. While there are other firms capable of providing benchmarking services, only McKinsey offers Quotient benchmarks and 360-degree benchmarks.” The response goes on to discuss the uniqueness of McKinsey’s datasets and how McKinsey has exclusive rights to the datasets. However, this answer does not identify PSPC’s desired outcome that it seeks to fulfill through the NMSO. Instead, it provides a predetermined solution. There is no explanation regarding how this solution is the only way to meet client departments’ needs.

77. Further, one of the TB 7 questions asked PSPC to “Describe the efforts taken to identify a variety of suppliers…” and in response PSPC answered “Efforts have been taken to identify whether other suppliers can provide the exact same surveys and results McKinsey provides and to obtain justification from McKinsey regarding the proprietary nature of its offerings.” However, this response did not provide a description of these efforts to identify other suppliers as the question requires and there was no documentation on file to demonstrate what these efforts entailed.

78. Consequently, the McKinsey Benchmarking Services NMSO may have been improperly established on a non-competitive basis, as the sole-source justification documentation provided did not demonstrate that PSPC had met its responsibility to ensure the rationale was adequately supported.

79. In its response to this report, PSPC indicated that it accepts the recommendations in their entirety and most of its findings, however they stated “there were legitimate reasons for taking the approach PSPC did when it awarded the non-competitive NMSO and using that fact as the impetus for all subsequent call-ups.” The full PSPC response to this report is provided in Section VIII, Organizational Responses.

Recommendation 4:

PSPC should put in place appropriate governance over the establishment of non-competitive NMSOs for professional services, including a review of the decision to pursue a non-competitive procurement strategy.

Security considerations in the McKinsey Benchmarking Services National Master Standing Offer

80. The McKinsey Benchmarking Services NMSO had conflicting information with respect to security. The first page of the NMSO in the Security section stated “This Standing Offer shall not be used for call-ups where security requirements have been identified.” When no security requirements are identified, it means there are no restrictions with respect to who completes the work, where in the world it is completed, or how information related to the work is communicated or stored. The call-up procedures in the NMSO, however, required that authorized users provide a completed SRCL, if applicable, to PSPC with their request and “where the client determines that there is no security requirement, there is no SRCL required in the call-up.”

81. It was noted that 7 of the 19 call-ups issued against the McKinsey Benchmarking Services NMSO contained security requirements. Based on the wording of the NMSO (which was never amended) the issuance of these call-ups should not have been requested by the client departments or permitted by PSPC. In response to OPO’s observation regarding the contradictory security provisions of the McKinsey Benchmarking Services NMSO, PSPC confirmed that it was their intention to allow for call-ups that contained a security requirement.

Call-ups issued against the McKinsey Benchmarking Services NMSO

82. The 19 non-competitive call-ups issued against the McKinsey Benchmarking Services NMSO were awarded to McKinsey between March 22, 2021 and January 9, 2023. The total initial contract value of the call-ups was $47.0 million (total amended value was $48.8 million). OPO noted that 97.5% ($45.8 million) of the initial value of call-ups issued against the NMSO was for expert support services (i.e., the delivery model for the benchmarking solutions), while only 2.5% ($1.2 million) was for the proprietary benchmarking solution fee (i.e., Digital 20/20 suite and OrgSolutions: Organizational Health Index).

Consistency with Government Contracts Regulations exceptions that permit non-competitive contracting

83. As noted earlier, section 6 of the GCR provides for an exception when only one supplier is capable of performing the work (GCR section 6(d)). With respect to these situations, the Treasury Board Secretariat requires departments to respond to a set of questions to explain and justify why exception 6(d) of the GCR has been invoked to allow a sole-source contract. It was necessary for the 19 call-ups to include these justifications on file in order to support the use of a non-competitive procurement process and the selection of the McKinsey Benchmarking Services NMSO as the appropriate procurement vehicle.

84. Per the PSPC Supply Manual, "While the client department must provide the rationale for any exception to soliciting bids, it is the responsibility of the contracting officers to make sure that the rationale can be adequately supported…” and “Use of any of the GCRs exceptions must be fully justified by the contracting officer with appropriate documentation that sets out the procurement strategy as well as the rationale for the exception used, placed on the procurement file."

85. The current Directive on the Management of Procurement further highlights the responsibilities of the business owners and contracting authorities in this regard. Section 4.9.6 of the Directive states that business owners are responsible, in collaboration with contracting authorities, for “providing a justification for using any of the exceptions to soliciting bids in the Government Contracts Regulations.” Further, section 4.10.1.4 states contracting authorities are responsible for “justification for using a non-competitive process, in accordance with the Government Contracts Regulations (including the sole-source exception invoked, the rationale for its use, and any associated documentation).” Similar requirements applied under the former Treasury Board Contracting Policy section 10.2.6 which stated (in part) “any use of the four exceptions to the bidding requirement should be fully justified on the contract file.”

86. Among the 19 call-ups reviewed, only 1, a call-up issued by PSPC on behalf of ESDC, included a documented justification for the use of a non-competitive process that provided a rationale in support of the selection of the McKinsey Benchmarking Services NMSO. In the remaining 18 call-ups, PSPC as the contracting department did not request documentation to support the justification or rationale. PSPC informed OPO that starting in January 2023, client departments were asked to provide a sole-source justification for each request made against the McKinsey Benchmarking Services NMSO. As stated previously, the NMSO expired in February 2023.

87. In the 1 file for which a justification for the use of a non-competitive process was documented, the justification did not appear to be fully accurate and supportive of the GCR exception. While it is noted that the PSPC Contracting Authority challenged ESDC to provide responses to the TB 7 questions that further justified the rationale for sole-sourcing, there was no further pushback to the final version of responses (highlighted below).

- For 1 of the 3 ESDC call-ups – the answers to the TB 7 questions did not establish a link between McKinsey’s exclusive rights to its benchmarking solutions and ESDC’s operational requirements. Rather, ESDC stated “The main source of justification supporting the sole-source of this requirement is due to the proposed vendor’s specialized expertise and knowledge across the world in large scale and complex transformations.” ESDC went on to note “The Department requires access to a broad set of technical, strategy, project management and execution skills in digital and Information Management/Information Technology (IM/IT) programs. McKinsey & Company upholds a prestigious reputation and experience in the required services that has led to a recommendation for a non-competitive process.” Further, ESDC’s reasoning did not provide a sufficient basis for PSPC to reasonably conclude that McKinsey held exclusive rights to the extent that it was the only supplier able to supply the benchmarking services. As the value of this call-up was $5.7M (including taxes), PSPC sought and obtained approval for this procurement from the Minister of Public Services and Procurement.

88. Not having a rationale on file poses a risk to fairness, openness and transparency as departmental officials cannot demonstrate they have issued non-competitive contracts in accordance with the GCR requirements. This situation is unique given the sheer number of non-competitive contracts (18 of 19 call-ups) lacking a justification on file, and their combined amended value of $43 million. OPO considers this significant shortcoming to be a serious threat to the fairness, openness and transparency of the procurement process.

Development of the statement of work

89. OPO’s observations regarding the development of the SOW for call-ups issued against the McKinsey Benchmarking Services NMSO do not include the 2 EDC contracts and 1 BDC contract. As such, this section includes the results from the 16 call-ups issued by PSPC on behalf of federal government departments.

90. Per section 16.1.1 of the Contracting Policy, “statement of work [SOW] or requirements description should clearly describe the work to be carried out, the objectives to be attained and the time frame.” Further, it goes on to state that a SOW “should also identify the specific stages of the work, their sequence, their relationship to the overall work in general and to each other in particular.” PSPC’s Supply Manual notes the client is responsible for developing the SOW.

91. Of the 16 call-ups reviewed, only 1 call-up, issued by PSPC on behalf of CBSA, had a SOW that defined the call-up specific requirement and formed part of the resulting contract. None of the remaining 15 call-ups included a description of the objectives to be attained or details of the work to be carried out that would normally be expected to be included in a SOW specific to the requirement. The contract documents simply referred to the generic SOW outlined in the McKinsey Benchmarking Services NMSO, or in 1 case did not even reference the SOW from the NMSO.

92. In terms of file documentation, in 14 of 16 call-up files OPO found that the earliest document on file was the proposal from McKinsey. As a result of the lack of documentation regarding the client’s requirement, it was unclear what the requirements were intended to be independent of McKinsey’s input.

93. Given the lack of SOWs in these call-ups (coupled with the aforementioned missing non-competitive justifications), the files did not demonstrate that the PSPC Contracting Authority conducted an adequate review in the vast majority of cases in order to confirm alignment between the department’s requirement and the scope of the McKinsey Benchmarking Services NMSO. OPO noted that the call-up procedures of the NMSO did not require authorized users to provide a requirement-specific SOW in order for PSPC to issue a call-up.

94. The inadequacy of the detail surrounding the requirement also extended to 1 file from DND where a $1.8 million amendment to a call-up was not sufficiently justified. Details are provided below:

- For 1 of the 12 DND call-ups with an amended value of $5,718,569 – during the call-up period, McKinsey provided an updated proposal to DND along with a presentation detailing additional expert support services for the call-up. There was no documentation on file related to DND's request for a revised proposal from McKinsey for the additional work. It is unclear who identified the need for additional expert support services – DND or McKinsey. The amendment extended the duration of the call-up and also increased the contract value from $3,916,335 to $5,718,569. Per DND’s justification for the amendment, legitimate delays to starting the work were noted which required an extension to the call-up’s end date. With respect to the additional funds to be added, DND noted “…since the contract was first signed, DND/CAF has worked with the contractor to better define the scope of the work required to perform a cultural assessment of the organization. This revised scope included a number of activities that needed to take place to ensure the assessment process was sufficiently robust and the findings were of value from an organizational perspective." The additional work added 6 weeks of expert support services. However, based on the justification provided by DND, it is not clear what the identified changes to the scope of work were or what specific activities were required from McKinsey in order to justify the need for additional funds. The amendment to the call-up did not include a description of the additional work to be performed.

95. The lack of a SOW makes it difficult for departments to hold a contractor to account in the event of future contractual disputes surrounding the expectations of work to be completed. As well, this lack of documentation surrounding the specifics of the requirement also creates a risk that contract-splitting could go unnoticed as the scope of the original requirement is not clearly documented.

Recommendation 5:

PSPC should ensure any future established non-competitive standing offers include call-up procedures that require written justification for issuing a call-up without competition. In the case of standing offers for professional services, the call-up procedures should require authorized users to prepare a statement of work (SOW) specific to their requirement.

Verification of resource security clearances

96. Of the 19 call-ups reviewed, 7 had security requirements. However, in 4 of the 7 call-ups (3 ESDC, 1 DND), the files did not contain documentation to confirm that resources had the required Reliability status personnel security clearances.

Line of enquiry 3: Practices for issuing contract amendments and task authorizations to McKinsey

97. A contract amendment is an agreed addition to, deletion from, correction or modification of a contract. As discussed in section 12.9 of the Contracting Policy “contracts should not be amended unless such amendments are in the best interest of the government, because they save dollars or time, or because they facilitate the attainment of the primary objective of the contract.” The Policy also goes on to state that “many contract amendments are, in fact, prudent. Often contract amendments or probable amendments can be foreseen when the initial contract is contemplated.”

Overall, contract amendments were appropriate and were in line with policy and guidelines

98. Of the 32 applicable contracts reviewed, 10 had been amended. These amendments fell into one of four categories. Note that some of these 10 contracts had more than one amendment and are counted under multiple categories:

- administrative amendments (5 contracts)

- unplanned amendments to extend the contract period with no increase in contract value (4 contracts)

- planned amendments to exercise previously contemplated option periods (3 contracts)

- unplanned amendments that increased the contract value (5 contracts)

99. OPO identified issues with 3 contracts that had been amended. In the first case, for a DND contract, as discussed in paragraph 94, the amendment to a call-up for McKinsey benchmarking services was not sufficiently justified. In the second case, for a CBSA contract, the contract amendment was not on file and it could not be confirmed that work under the amendment was consistent with the scope of the original contract. In the third case, for a VAC contract, the contract amendment was not issued prior to the contract expiry date. The latter two examples are described below:

- In October 2017, CBSA awarded a contract with task authorizations to McKinsey for executive support services for various CBSA transformation initiatives valued at $791,000. In January 2018, a contract amendment request was prepared to increase the contract value by $1,000,000 to cover the cost of additional work. However, the executed contract amendment was not on file nor were copies of properly executed task authorizations. Thus it is unclear if work performed was consistent with the scope of the contract.

- In February 2020, VAC awarded a non-competitive contract valued at $24,860 to McKinsey for business consulting and change management services. The contract end date was September 30, 2020, however, the work was not completed by this time due to the COVID-19 pandemic and work continued after this period following verbal instruction to McKinsey from VAC. An amendment was later issued on February 9, 2021 to extend the end date of the contract (i.e., 4 months after it had expired).

100. Continuing work without a written contract places both parties at risk. For the supplier, work outside of a contract could result in non-payment and assumption of risks that would no longer be covered by covenants and insurance. It is always advisable to document all decisions related to the procurement and save them to the contracting file. Parties should not perform work in circumstances when the written contract is not effective whether before or after the stated effectivity period.

Line of enquiry 4: Disclosure of information associated with contracts awarded to McKinsey

Contracts proactively published, but information was inaccurate

101. Under the former Treasury Board Contracting Policy and the current Directive on the Management of Procurement, departments are required to proactively publish contract information. The Treasury Board Secretariat Guide to the Proactive Publication of Contracts, formerly titled the Guidelines on the Proactive Disclosure of Contracts, provides guidance to departments on the identification, collection, reporting and proactive publication of contract information. Government policy requires quarterly proactive publication of information on the following:

- A contract when its value is over $10,000

- A positive or negative amendment when its value is over $10,000

- A positive amendment when it modifies the initial value of a contract to an amended contract value that is over $10,000

102. Of the 32 contracts reviewed, 28 were required to be proactively published. For applicable contracts, OPO searched proactively published contract information on the Open Government web site (open.canada.ca) to determine if all 28 contracts and applicable amendments were proactively published. With the exception of 1 contract, proactive disclosure information was publicly posted to the Open Government web site. Furthermore, all applicable amendments were publicly disclosed.

103. For the 27 contracts that were proactively published, OPO found that 19 contained one or more inaccuracies in the published information, with the most notable centering around trade agreement applicability, solicitation procedure, and limited tendering reason.

- The proactive publication website allows for the identification of applicable trade agreements. In 17 instances, the published information contained inaccuracies, either not identifying trade agreements that applied at the time of the procurement or identifying additional trade agreements that did not apply at the time of the procurement.

- In 10 instances, the published information contained inaccuracies for the solicitation procedure. The solicitation procedure intends to account for whether the procurement in question was done under a competitive versus a non-competitive method. All contracts under this finding were call-ups issued against the NMSO, and inaccurately described the method as “traditional competitive” when in fact the method was non-competitive.

- In 14 instances, the published information contained inaccuracies for the limited tendering reason. All contracts under this finding were call-ups issued against the NMSO and the Open Government web site stated that no limited tendering reason applied, implying open competition when in fact it should have stated “exclusive rights” had been used to justify awarding contracts without competition.

104. The accurate disclosure of information related to government contracts is a critical element of the Government’s commitment to transparency in procurement. Proactive publication of information plays a key role in informing Canadians about these contracts. Clarity on the government’s spending practices is important for the supplier community as it enables them to make well-informed business decisions related to their participation in procurement processes. It is crucial the information inputted into these systems accurately reflects the procurement process without exception.

VII. Conclusion