Procurement Ombudsman’s Annual Report 2019-2020

We listen. We connect. We resolve.

- Mail:

- Office of The Procurement Ombudsman

400-410 Laurier Avenue West Ottawa, ON K1R 1B7 - Toll-free:

- 1-866-734-5169

- Teletypewriter:

- 1-800-926-9105

- Email:

- ombudsman@opo-boa.gc.ca

- Twitter:

- @OPO_Canada

- Catalogue number:

- P110-1E-PDF

- International Standard Serial Number (ISSN):

- 1928-6325

Letter to the Minister of Public Services and Procurement

Dear Minister,

Pursuant to paragraph 22.3(1) of the Department of Public Works and Government Services Act, it is an honour to submit the Procurement Ombudsman’s Annual Report for the period of April 1, 2019 to March 31, 2020 (fiscal year 2019-20).

Yours sincerely,

Alexander Jeglic

Procurement Ombudsman

Ottawa, July 31, 2020

On this page

- 1. Message from the Procurement Ombudsman

- 2. Evolving role of the ombudsperson

- 3. Supporting the supplier community

- 4. Diversifying the federal supply chain

- 5. Strengthening the federal procurement community

- 6. Engaging with the ombudsperson community

- 7. Establishing a presence across Canada

- 8. 2019-20 by the numbers

- 9. Top 10 issues—What we heard

- 10. How we help

- 11. A word on our commitment to you

- Appendix A

1. Message from the Procurement Ombudsman

Looking back, 2019-20 has been unlike any other year. The coronavirus has changed almost everything in our lives, from how we socialize with friends and family, to how we use technology to work from home. I would like to thank all the front-line workers who have put their own safety at risk to help us through this crisis, the procurement practitioners who put out the call for much-needed goods and services, and the many thousands of Canadian businesses (suppliers) who stepped up and answered that call.

From a procurement perspective, exceptional circumstances can require a broader application of discretion in the interest of expediency. However, it is also imperative that transparency not be lost in the process. At times like these, Canadians must be assured their government is exercising responsible stewardship over public funds, and transparency is the means of providing this assurance. Procurement practitioners should still, as always, diligently document their files to ensure their decisions can withstand public scrutiny.

As we adapt to the many changes happening in the world of procurement, including e-procurement, vendor performance management and policy renewal, I remain committed to doing everything I can to safeguard fairness, openness and transparency in the federal procurement process.

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the need to simplify an overly burdensome procurement process, an issue I often hear about from our stakeholders. At a time when buyers and suppliers are working together to address a pressing matter of public health, it is especially clear they should not be hindered unnecessarily.

As we adapt to the many changes happening in the world of procurement, including e-procurement, vendor performance management and policy renewal, I remain committed to doing everything I can to safeguard fairness, openness and transparency in the federal procurement process.

My office made meaningful progress in a number of key areas in 2019-20, which are detailed further in this report. We continued to work collaboratively with suppliers and federal departments to help resolve problems by lending assistance and providing practical solutions. This cooperative approach is consistent with the tone I have strived to set with our stakeholders, as I believe it results in the most effective solutions to procurement-related issues and disputes.

Update on priorities

Over the past year, my team and I have continued to focus on the 4 priorities I established at the beginning of my mandate in April 2018. Here are some highlights of progress in these areas.

Simplification

The unnecessarily complex nature of the federal procurement process is an issue I hear about regularly from both suppliers and federal departments. This complexity is a constant source of frustration, creating overly burdensome barriers to contracting with the federal government. Given this is a large-scale issue that requires a sustained commitment, I strongly encourage federal departments to work together to identify more ways to simplify and streamline the process. This may require a higher degree of risk tolerance, building more flexibility into the process and eliminating unnecessary requirements in mandatory and rated criteria. Including unnecessary criteria in solicitations only because they have been included in the past and adopting a zero-risk tolerance approach to procurement is not the way forward. The burden currently weighing on suppliers and departments will only be lifted once deliberate steps are taken to effect meaningful and permanent change.

For our part, my team and I continued offering practical solutions to solve specific problems. We identify these problems through our procurement practice reviews, which are largely selected based on the “Top 10” list of issues in federal procurement. This is a list we compile annually based on the issues we hear about most frequently from our stakeholders.

My office’s reviews of departments’ procurement practices now include a section dedicated to simplification, in order to identify both good practices and opportunities for improvement. One recent example of a good practice we noted is the use of standardized solicitation documents and processes to ease the burden on suppliers. If each department uses unique solicitation documents and processes, it significantly increases the burden on suppliers, particularly those who supply the same good or service across multiple departments. Using standardized documents and processes decreases the cost to bid for suppliers and potentially lowers bid prices for departments. Another example of simplification is the use of a set package of evaluation documents to ensure all evaluations are conducted in a consistent manner so departmental officials don’t have to apply a different process every time they are involved in a procurement. These examples demonstrate that both suppliers and departments can benefit from steps taken to simplify the procurement process. My office publishes these reviews on our website so all federal departments can access the information and implement improvements within their own organization.

Transparency

Since the start of my mandate, I have been increasing the number of documents published online to be as transparent as possible about the work we do. Both our five-year Procurement Practice Review Plan (2018-23) and a compliance review that was completed by an external audit firm are now available on our website. The review assessed the Office of the Procurement Ombudsman’s (OPO) compliance with relevant sections of the Department of Public Works and Government Services Act and the Procurement Ombudsman Regulations (the Regulations). The compliance review concluded OPO has a robust set of processes and practices in place to support compliance with legislative authorities. In addition, the review suggested OPO adopt a secure electronic file transfer mechanism, and consider holding formal meetings to consider the impact of OPO recommendations on government operations. We are in the process of implementing both recommendations. The review also noted OPO’s effectiveness is often limited due to the voluntary nature of departmental collaboration, in particular our inability to compel departments to produce relevant documents.

Knowledge Deepening and Sharing

In 2018-19, OPO launched a Knowledge Deepening and Sharing (KDS) initiative to help our stakeholders better understand key issues in federal procurement. Topics covered that year were dispute resolution mechanisms for vendor performance management, and low dollar value contracting. Both reports are published on our website, and were the subject of numerous presentations and discussions over the past year with both suppliers and federal departments.

In 2019-20, we launched 3 new KDS studies: Late payments, Social procurement and Emergency procurement. More information on these studies is provided later in this report.

Through the publication of KDS studies, OPO intends to share knowledge and provide meaningful guidance to suppliers and federal departments.

Growth in dispute resolution services

I believe the Government of Canada should be transparent about the recourse mechanisms available to suppliers when a dispute arises about the terms and conditions of a federal contract. As such, I wrote to the deputy heads of 83 federal departments in 2018-19 and asked them to add a clause to their contracts with suppliers referencing OPO’s dispute resolution services. The response to the request was positive. In 2019-20, my office worked directly with stakeholders to advance this important initiative.

Unfortunately, not all departments actioned my request. I will be writing to deputy heads again in 2020-21 to remind them to include such clauses in their contracts. If departments want to be transparent and let suppliers know about recourse mechanisms such as OPO’s dispute resolution services, the best place to do that is in the body of the contract itself.

My office also took steps to make our dispute resolution process as simple and accessible as possible. We published a one-page “What to expect” guide on our website to provide clear and concise information about the process. We also began exploring options to offer online mediation services to reduce costs and increase accessibility for parties who would otherwise have to travel to participate in a mediation session.

“If departments want to be transparent and let suppliers know about recourse mechanisms such as OPO’s dispute resolution services, the best place to do that is in the body of the contract itself.”

Update on regulatory changes

As noted in my previous annual report, the current Regulations limit the value and effectiveness of my office in at least 2 key areas:

- They prevent me from being able to recommend compensation of greater than 10% of the value of the contract when the complaint is about the award of a contract. My office is one of the only avenues of recourse available to Canadian suppliers for complaints about the award of contracts below $26,400 for goods and $105,700 for services. As such, the maximum compensation they can receive is $2,640 and $10,570, respectively. These limited amounts often do not reflect the time and effort of preparing and submitting a complaint with my office, or the cost that went into the preparation and submission of the bid.

- The Regulations do not give me the authority to compel federal departments to provide the documentation necessary to conduct reviews of supplier complaints and reviews of departmental procurement practices. Without this authority, my office can only review the information that is voluntarily disclosed by the department. This limitation poses significant challenges to the principles of fairness, openness and transparency, for which the position of Procurement Ombudsman was established to safeguard.

Given the above, I am proposing the following 2 changes to the Regulations:

- Enable the Procurement Ombudsman to recommend compensation of more than 10% of the value of the contract, up to the amount of actual lost profit incurred by a complainant

- Enable the Procurement Ombudsman to compel departments to provide the documentation necessary for the Office of the Procurement Ombudsman to conduct reviews of supplier complaints and reviews of departmental procurement practices

I believe these changes are necessary to improve the value and effectiveness of my office and I will continue to push for their implementation.

To our stakeholders

As we navigate the many changes in the procurement landscape, including those arising from the COVID-19 pandemic, I want to reaffirm my commitment to help you. The year ahead will be challenging and issues will undoubtedly arise. When they do, please contact my office. We will be ready, as always, to help you resolve them.

Sincerely,

Alexander Jeglic

Procurement Ombudsman

2. Evolving role of the ombudsperson

Ombudsperson—complicated word, simple meaning

In the federal government context, an ombudsperson is a public official who acts as an impartial intermediary between the public and the Government of Canada. In simpler terms, an ombudsperson works with both parties to help them resolve issues. In one word, an ombudsperson “helps.”

The Office of the Procurement Ombudsman

Our mission

We promote fairness, openness and transparency in federal procurement.

Our mandate

The Department of Public Works and Government Services Act provides the authority for the Procurement Ombudsman to exercise his mandate as follows:

- Review procurement practices: Review the practices of federal departments for acquiring goods and services to assess their fairness, openness and transparency, and make appropriate recommendations to the relevant department

- Review complaints—contract award: Review complaints respecting the award of a contract for the acquisition of goods below $26,400 and services below $105,700, where the criteria of the Canadian Free Trade Agreement would otherwise apply

- Review complaints—contract administration: Review complaints respecting the administration of a contract for the acquisition of goods or services, regardless of dollar value

- Provide alternative dispute resolution: Ensure that an alternative dispute resolution process is provided for federal contracts, regardless of dollar value, if the parties to the contract agree to participate

“In short, we help resolve contract-related issues and disputes between Canadian suppliers and the Government of Canada.”

Our evolving role

Looking ahead, we want to be even more responsive to suppliers and federal departments that reach out to us, and more effective at promoting fairness, openness and transparency in federal procurement. To successfully deliver on our mandate, we must play the role of investigator in certain instances, and mediator in others. Both of these roles require us to be seen as an independent, credible organization that conducts its business free from actual or perceived interference. With this in mind, we are continuing to look at existing models and governance structures of similar organizations in Canada in order to assess how they are able to most effectively deliver on their mandates.

Connecting our stakeholders

By virtue of our role as a third-party intermediary, we are well positioned to connect suppliers and federal departments and do so regularly. In 2018-19, we launched 2 key initiatives, Knowledge Deepening and Sharing and Diversifying the Federal Supply Chain, which we highlight in section 4. They were designed to connect the right people and share practical information. We hope these initiatives will help create a positive change in the federal procurement process.

Knowledge Deepening and Sharing

We remain dedicated to advancing research on topics that matter to stakeholders in the federal procurement process. To select topics, we consider emerging trends, legislative changes, government priorities and the nature and frequency of issues reported to us by suppliers and federal departments.

The studies consist of:

- Detailed literature reviews

- Analysis of regulatory and policy frameworks at the federal, provincial/territorial and municipal levels

- In-person interviews

- Analysis of data captured by our office including our annual “Top 10” list of issues in federal procurement

In 2019-20, we substantially completed 3 studies:

- Late payments

- Social procurement

- Emergency procurement

All 3 reports will be available on our website.

-

Late payments

In both 2018-19 and 2019-20, the issue of late payments was on our annual “Top 10” list of issues in federal procurement. This study is intended to help our stakeholders understand how the concept of late payments is viewed differently by suppliers and federal departments, and explore some of the root causes of late payments. Most importantly, it highlights steps that can be taken by both parties to help ensure that invoices are received and paid in a timely manner. We hope that a better understanding of the issues surrounding late payments, combined with the implementation of mitigation measures, will contribute to a decrease in the number and duration of late payments in the federal procurement process. -

Social procurement

Social procurement can be defined in various ways. Generally speaking, it is a growing international practice that refers to using procurement to achieve strategic social, economic and workforce development objectives. This study provides an overview of key success factors for organizations looking to adopt social procurement practices, specifically with regard to increasing supplier diversity and integrating workforce development benefits into their procurement processes. It further highlights why factors such as securing senior-level support, establishing an approach to certification and implementing a robust data collection framework are critical to success. As social procurement encompasses a wide range of objectives and strategies, we plan to conduct additional research on this topic in the future. -

Emergency procurement

We launched this study in March 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic to examine the use of emergency procurement practices in past disasters in Canada and abroad, and to determine if any lessons can be drawn from those experiences and applied to similar situations in the future. The study identifies effective procurement practices such as increasing delegated spending authorities and non-competitive contracting limits, and considers the risks associated with these approaches. It also highlights why it is critical to have a framework in place to bring consistency and order to what is often an urgent and chaotic environment.

3. Supporting the supplier community

Given our national mandate, we attended many supplier-focused events across the country in 2019-20 to raise awareness of our services and provide a platform for suppliers to share their experiences in doing, or trying to do, business with the federal government. We know the process is not always an easy one and feel it is important to give suppliers an opportunity to be heard and understood. We gather supplier feedback for multiple purposes including the selection of topics to review, as well as compiling our annual “Top 10” list of issues in federal procurement which helps us develop practical solutions to those issues. We also met with a number of new and returning members of Parliament to inform them of our services should any suppliers in their ridings come forward with an issue about federal procurement.

When suppliers contact our office, we respond by taking any number of steps to assist them. We often work with the supplier and department to help them find a quick and informal solution to a problem they are unable to resolve amongst themselves. We call this shuttle diplomacy. Simply put, we go back and forth between the supplier and the department as many times as needed to re-establish communication, help each party understand the other’s point of view and solve the problem. For example, if a supplier has not been paid for services rendered and has not been able to resolve the issue, we will contact the department on their behalf, determine the reason for the delay and work with the parties to ensure payment as soon as possible. In some cases, we provide step-by-step instructions on how to file a complaint or request dispute resolution services. In other cases, we refer suppliers to the Canadian International Trade Tribunal or the Office of Small and Medium Enterprises. These are organizations that may be able to investigate procurement complaints, or provide advice on how to obtain government contracts, respectively. In all cases, we do everything we can to help resolve the issue.

4. Diversifying the federal supply chain

We hosted our first Diversifying the Federal Supply Chain Summit in Ottawa in March 2019. Our goal was to connect underrepresented Canadian business owners with representatives from federal government programs and private sector organizations who could explain the federal procurement process and help access opportunities. The positive response from participants demonstrated the value in hosting summits of this type. That said, we knew more could be done to respond to the ongoing needs of diverse business owners by providing more practical information to help improve their odds of obtaining federal contracts.

In March 2020, we hosted our second Diversifying the Federal Supply Chain Summit in Toronto. Expanding on the half-day program offered in Ottawa, we introduced a full-day program that included presentations, panel discussions and practical workshops focused on providing hands-on skills and assistance. The Minister of Public Services and Procurement, the Honourable Anita Anand, opened the Summit with a keynote speech. The rest of the morning focused on highlighting positive public and private sector developments toward diversifying the federal supply chain. We wanted to ensure the groups for whom various programs, services and initiatives have been put into place were aware of their existence and benefitting from them. It was about bringing the right people together in the same room and sharing information about these programs with the intended audience.

The Summit was also a forum for open, candid and meaningful exchanges between federal representatives, the private sector and underrepresented business owners. In the afternoon, participants attended practical workshops designed to help them navigate the federal procurement process, which can be complex and administratively burdensome. One of the workshops delivered by Public Services and Procurement Canada (PSPC) helped participants understand the process to obtain a security clearance, a necessary step for many suppliers wanting to do business with the Government of Canada. We also invited business owners who have been successful in obtaining federal contracts to share their story with others, including key factors to their success and lessons they have learned along the way.

Given the Summit attracted 350 registrants from the Greater Toronto Area and beyond, we plan to host our third Diversifying the Federal Supply Chain Summit in the near future. We will carefully consider both the positive and constructive feedback received from participants to ensure we meet their ongoing needs and expectations.

5. Strengthening the federal procurement community

Beyond our core mandate activities, we also regularly share information, knowledge and practical solutions with procurement practitioners across Canada. This is part of our ongoing commitment to help strengthen the community, something our stakeholders have indicated is needed.

In 2019-20, we shared information at a number of events, including the Canadian Institute of Procurement and Materiel Management (CIPMM) Regional Workshop in Halifax, the Canadian Public Procurement Council Annual Forum in Toronto, and Client Advisory Board (Acquisitions Program, PSPC) meetings in Ottawa. We also met with representatives from Supply Chain Canada in Toronto and with government procurement teams in several cities including Edmonton, Saskatoon, Winnipeg, St. John’s and Fredericton. The purpose of engaging with stakeholders at these events is simple: we listen, we share information and we help. We learn about the issues they are facing in their role as procurers, so we can share this information with senior federal decision-makers. We let them know about our dispute resolution services in case they require our help. And we tell them about issues brought to our attention by suppliers so they can better understand the impact of the federal procurement system on Canadian businesses.

In line with our commitment to contribute to the development of procurement practitioners, we also participated in several learning events in 2019-20. We delivered presentations in the National Capital Region (NCR)—one to new recruits at Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat’s (TBS) “Onboarding Day” and another to procurement practitioners enrolled in PSPC’s Intern Officer Development Program. We also presented at a joint CIPMM-Canada School of Public Service regional training course in Halifax. We participate in such events because our stakeholders have told us there is an ongoing need for recruitment, training and skills development in the community. The more information and knowledge procurement practitioners have, the better equipped they will be to perform successfully.

We also continued collaborating with TBS in 2019-20 to help attract exceptional candidates to the federal public service to fill procurement positions. We began this collaboration in 2018-19 in support of a Government of Canada recruitment initiative, which aims to attract candidates with the right competencies to fill vacant positions in the federal procurement community. We leveraged our existing national outreach program to reach out to graduating students at post-secondary institutions across the country on 9 occasions, and encouraged them to consider career opportunities in procurement within the federal government.

“We participate in such events because our stakeholders have told us there is an ongoing need for recruitment, training and skills development in the community. The more information and knowledge procurement practitioners have, the better equipped they will be to perform successfully.”

6. Engaging with the ombudsperson community

In 2019-20, we connected with a number of other ombudspersons at the federal, provincial/territorial and academic levels for the purpose of sharing best practices and finding ways to improve our services to Canadians. For example, through our membership in the Federal Ombudsperson Committee, we addressed topics of mutual interest including effective intake procedures, approaches to communications and outreach services, data management, investigative techniques and governance structures.

Though our mandate differs from other ombudspersons, there are still opportunities for valuable exchanges between our offices given the number of shared points of interest. We intend to continue meeting with various ombudspersons to maintain these discussions and explore opportunities to work together, especially for the purpose of reaching out to suppliers who may be selling goods and services to multiple levels of government.

7. Establishing a presence across Canada

Our legislative mandate is not limited to any particular geographic region within Canada, and we often travel to cities across the country to engage with stakeholder groups, review procurement files or provide dispute resolution services to suppliers and federal departments when contract disputes arise.

Suppliers across Canada have told us they feel there is a bias favouring their competitors located in the NCR because it is easier for them to obtain federal contracts by virtue of their proximity to head offices of federal departments. We have heard a similar sentiment from federal procurement officials across the country who feel detached and inadequately supported compared to their colleagues in the NCR. We are committed to promoting fairness, openness and transparency in federal procurement and that includes eliminating potential bias of any type.

As such, we launched a pilot project in 2019-20 and established pop-up offices in Victoria, Vancouver and Toronto to help ensure that more suppliers across Canada are aware of our presence and services. While there, we met with suppliers, federal procurement practitioners and representatives from a number of organizations including the Victoria Chamber of Commerce, the Greater Vancouver Board of Trade, Buy Social Canada and the City of Toronto. These networking opportunities allowed us to raise awareness of our services amongst those we were created to help. It also allowed us to obtain and share valuable information on what is and is not working in federal procurement. We plan to continue piloting pop-up offices in the future based on metrics such as the number of suppliers, volume of federal contracts, degree of federal presence and number of complaints received from regions across the country.

8. 2019-20 by the numbers

Number of cases

- 2019-20 Total number of procurement-related cases: 423

- 2018-19 Total number of procurement-related cases: 377

A case is generated each time a stakeholder brings a federal procurement-related issue to our attention. By stakeholder, we mean a supplier, a government buyer or an association representing either one. A case can include one or more issues.

Nature of casesFootnote 1

- 178 Cases related to the award of a contract

- 62 Cases related to the administration of a contract

- 160 Cases related to general procurement issues

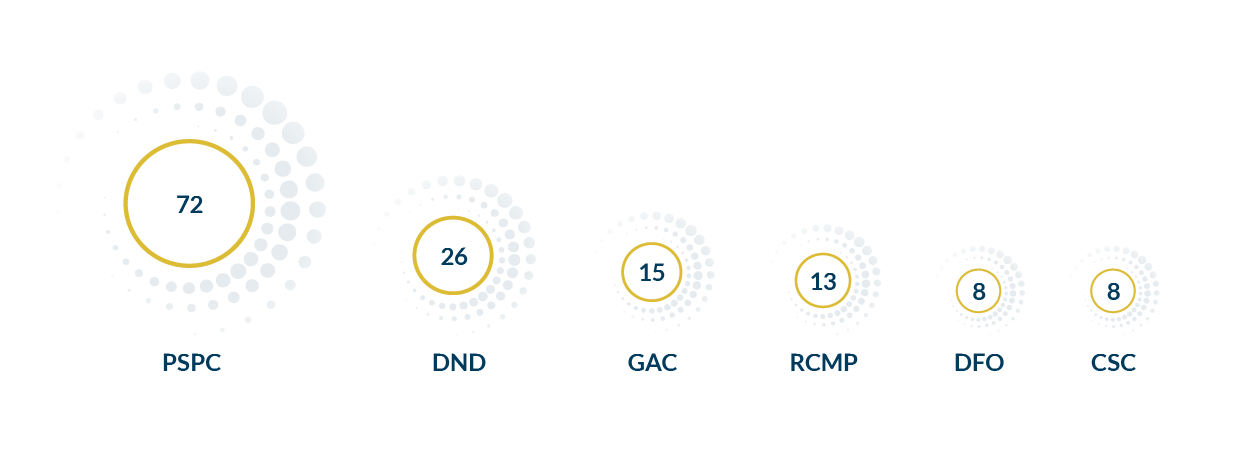

Origin of cases (top 5 departments)

Cases by contractingFootnote 2 departmentFootnote 3

- Public Services and Procurement Canada (PSPC): 72

- Department of National Defence (DND): 26

- Global Affairs Canada (GAC): 15

- Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP): 13

- Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO): 8

- Correctional Service Canada (CSC): 8

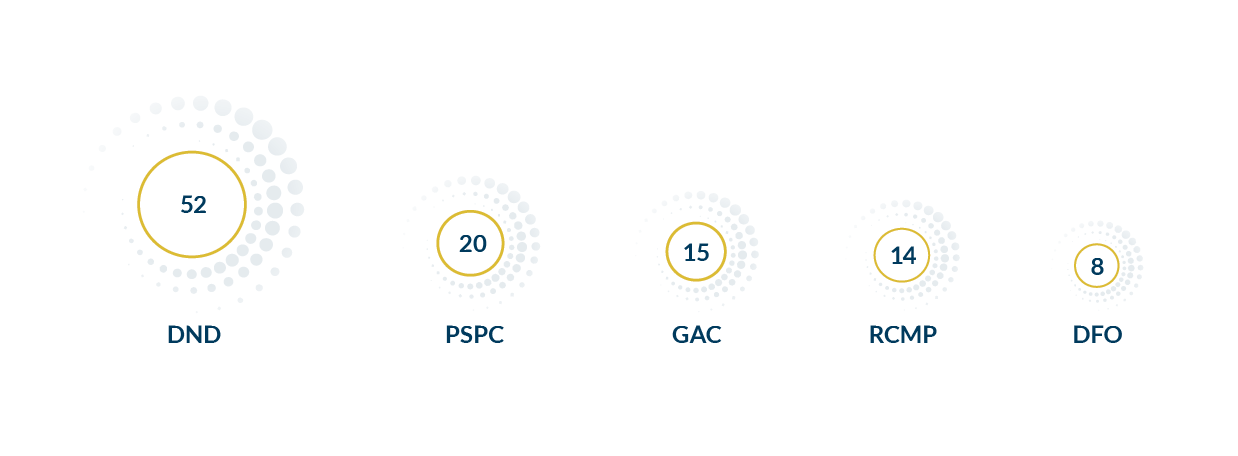

Cases by receivingFootnote 4 departmentFootnote 5

- Department of National Defence (DND): 52

- Public Services and Procurement Canada (PSPC): 20

- Global Affairs Canada (GAC): 15

- Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP): 14

- Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO): 8

Who contacted us?

- Suppliers and/or subcontractors: 324

- Federal officials: 34

- Procurement and supplier associations/councils: 14

- Others: 10

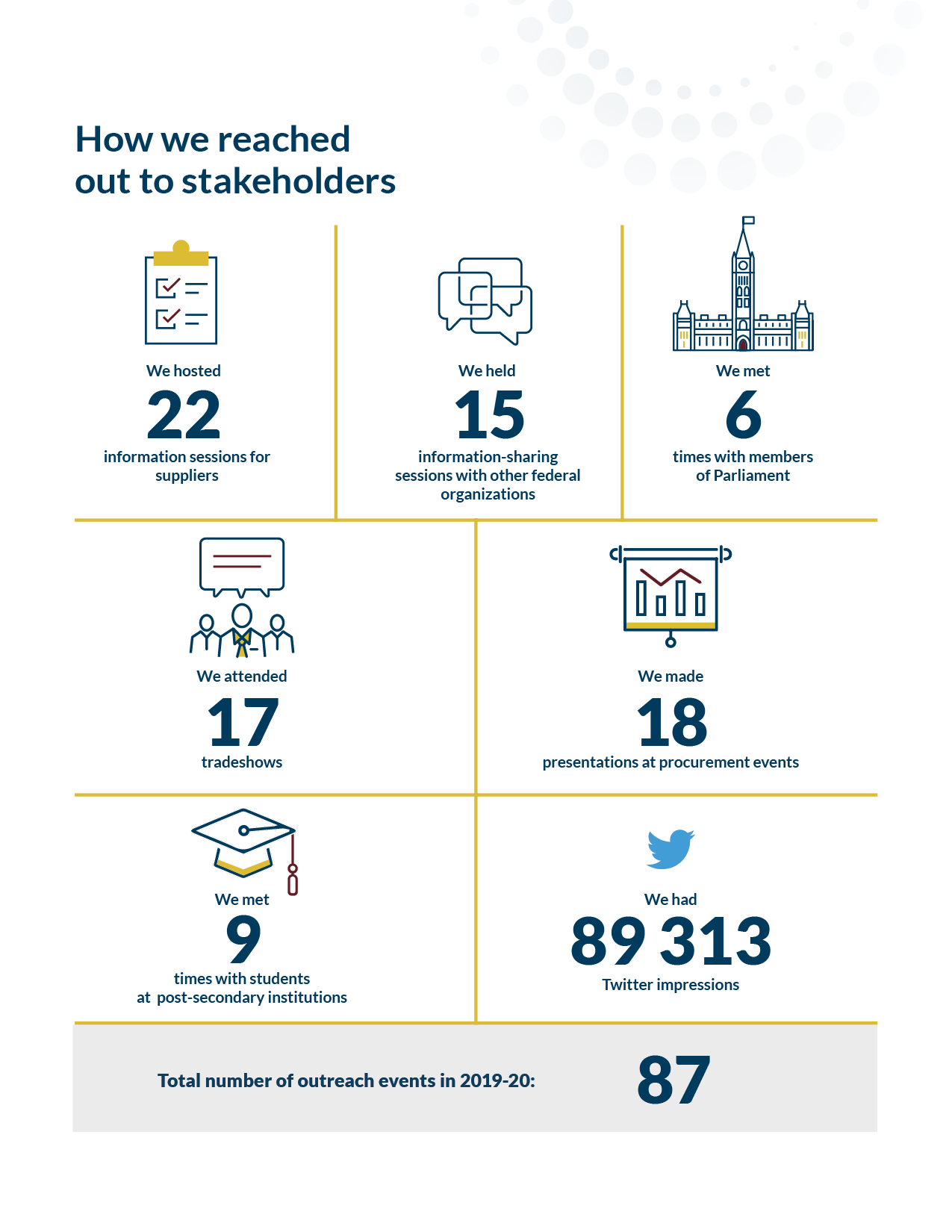

How we reached out to stakeholders

- We hosted 22 information sessions for the suppliers

- We held 15 information-sharing sessions with other federal organizations

- We met 6 times with members of Parliament

- We attended 17 tradeshows

- We made 18 presentations at procurement events

- We met 9 times with students at post-secondary institutions

- We had 89,313 Twitter impressions

- Total number of outreach events in 2019-20: 87

9. Top 10 issues—What we heard

We track the issues raised by our stakeholders in order to identify recurring issues in the federal procurement process. It is important to note that, for the purpose of compiling the “Top 10” list, we record the information as it is reported to us.

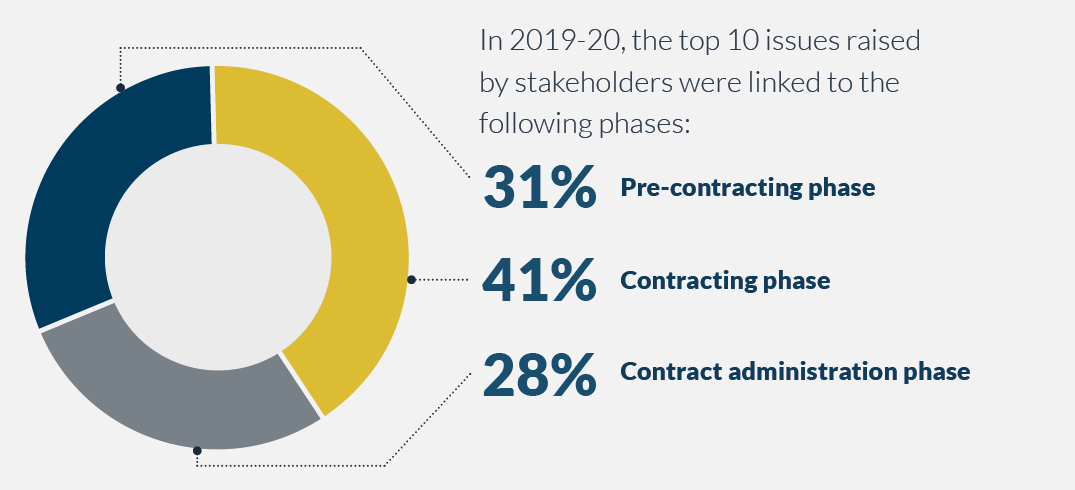

To ensure we best reflect the nature of each issue, we link the issues to 1 of the 3 main phases in the procurement process when such information is available. We use this information to identify and analyze the top issues over a given year, which helps us set the direction of our activities, including the development of the five-year Procurement Practice Review Plan (2018-23) and its standardized lines of enquiry.

In 2019-20, the top 10 issues raised by stakeholders were linked to the following phases:

- 31% Pre-contracting phase

- 41% Contacting phase

- 28% Contract administration phaseFootnote 6

Top 10 issues in federal procurement

In 2019-20, the top 10 issues, as reported by our stakeholders, were as follows (including an example for each issue):Footnote 7

| Rank | Issues | Quotes from Stakeholders | Number of Issues Reported |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | The stakeholder felt the evaluation had been incorrectly conducted. | “My proposal was evaluated incorrectly and we were deemed not to meet the mandatory requirements. However, the technical reviewers did not review one technical page of my submission.” | 29 |

| 2 | The stakeholder believed there was bias for or against an individual supplier or class of suppliers. | “[It seems] that they already knew who [they wanted to award the contract] to but it doesn’t look good if there is only one proposal [submitted].” | 17 |

| 3 | The stakeholder felt the department deviated from the terms and conditions of the contract. | “We were somewhat blind sided with the amount of work [required] as it was way beyond what was expected [as per the contract] and also way beyond our declared capacity.” | 15 |

| 4 | The stakeholder felt that the criteria was restrictive (content). | “My company is unable to qualify for a particular standing offer agreement due to us not having a certain amount of money in the [bank] or not being big enough in terms of number of employees even though the services required are not dependent on those factors.” | 14 |

| 5 | The stakeholder believed that their contract was wrongfully terminated. | “We have won this contract already and then it was cancelled and re-issued. We bid again and then they cancelled again. Now they are very quiet and we are not able to hear back from them at all.” | 10 |

| 6 | The stakeholder believed that the evaluation criteria was unfair/biased. | [Translation] “We believe that the evaluation criteria of the call for tenders and the allocation of points to the different criteria seemed to strongly favour a local company or even the company that already held the contract before the call for tenders for renewal.” | 10 |

| 7 | The stakeholder reported their payment is late. | “I found myself chasing payments for invoices […]. After several email[s], phone calls and escalations…I finally received payment […]. Some of these invoices were overdue more than 200 days […].” | 9 |

| 8 | The stakeholder received an inadequate response(s) or no response to their inquiry. | “We never got a written reply from [the department] about their reasoning [for not modifying the mandatory criteria] other than a no over the phone [even though] I requested a written reasoning for their denial. They never replied to us.” | 9 |

| 9 | The stakeholder believed that the contract was awarded to a non-responsive bidder. | “The contract was awarded to a company that [I know] [does] not meet the requirement, of having a secure location to store any of the vehicles.” | 9 |

| 10 | The stakeholder noted that the department is refusing to pay. | “The department will only pay 55% of the final invoice and are not willing to negotiate.” | 9 |

10. How we help

We offer dispute resolution services for federal contracts

We help resolve issues in several ways. If a contractual dispute or any other issue arises between suppliers and federal officials after the contract is put in place, we seek to help resolve the matter as quickly and informally as possible.

When an informal solution cannot be found, our Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) services provide an opportunity for parties to come together in a neutral setting and participate in a confidential and constructive dialogue. These services are offered for federal contracts regardless of dollar value and are led by our certified mediators. OPO-led ADR offers a quick and inexpensive alternative to litigation and has proven to be highly successful. We cover the cost of mediators and facilities. Participating parties are only responsible for their own costs such as travel and accommodation. In 2019-20, we provided our ADR services to parties across Canada including as far east as St. John’s and as far west as Vancouver.

In 2019-20, we received a total of 9 requests for ADR services:

- In 2 cases, both parties agreed to use our ADR process and their issues were formally resolved with a settlement agreement

- In 1 case, the supplier and the department were able to resolve the dispute before

- In 1 case, the ADR request was withdrawn by the supplier prior to starting the process

- In 3 cases, the nature of the request for ADR services did not meet the Regulations and could not be considered any further

- In 2 cases, the department declined to participate in the ADR process

In 2019-20, we also formally resolved 1 ADR process that we had launched in a previous fiscal year.

We review supplier complaints

If a supplier contacts us with a formal complaint about the award or administration of a contract that meets the criteria set out in the Regulations, we launch a review and produce a report on our findings. If the Procurement Ombudsman makes any recommendations in his report, we follow up with the department to confirm whether the recommendations were followed.

In 2019-20, we received 29 written complaints about the contract award process. 25 of those complaints were either withdrawn (for example, resolved through informal facilitation within 10 days) or did not meet OPO’s regulatory criteria (for example, contract value exceeded dollar thresholds). The other 4 complaints met the regulatory requirements and we launched an official review:

- 1 review was launched and completed

- 2 reviews were launched and will be completed within the legislative timelines

- 1 review was launched and subsequently terminated when the department cancelled the contested contractFootnote 8

Further details on each review are provided below.

Acquisition of translation services by the Administrative Tribunals Support Service of Canada (launched and completed)

In October 2019, the Procurement Ombudsman received a written complaint about a contract awarded by the Administrative Tribunals Support Service of Canada (ATSSC) for the provision of French-to-English translation services. ATSSC advised the complainant its bid was disqualified because it had included additional terms and conditions which, in accordance with the request for proposal, were not allowed. The Procurement Ombudsman concluded that to be fair to other bidders, and to maintain the integrity of the procurement process, ATSSC was required to deem the complainant’s bid non-compliant due to the inclusion of the additional terms and conditions. Furthermore, he also concluded that while the complainant correctly asserted that ATSSC is allowed to request clarification in certain circumstances, there is no obligation or requirement on ATSSC to do so, and therefore, ATSSC did not have to clarify the bid prior to determining compliance. Read the full report.

Reviews to be completed in 2020-21

When the Procurement Ombudsman launches a review of complaint, he must provide his findings or any recommendations within 120 working days after the day on which the complaint is filed. As noted above, 2 reviews will be completed in 2020-21. They will be reported on in our next annual report as a result of their timing.

Acquisition of janitorial services by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (launched and terminated)

In November 2019, the Procurement Ombudsman received a written complaint about a janitorial services contract awarded by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) for one of its detachments. The complainant, the incumbent service provider, claimed the contract had been awarded to a RCMP employee who worked in that detachment and had been involved in processing the invoices under the previous contract. The complainant claimed this gave the employee an unfair advantage and allowed the employee to underbid the complainant.

After we launched the review, the RCMP responded advising the circumstances of the procurement process were as stated by the complainant and, as such, the possibility of the employee having had an unfair advantage could not be ruled out. In January 2020, the RCMP issued a stop-work order, ordering the employee to immediately stop working on the contract. They terminated the contract in February 2020.

On March 3, 2020, we advised the parties that our review had been terminated. In his letter to the RCMP, the Procurement Ombudsman indicated the complaint clearly had merit, given information provided by the complainant and the RCMP. Had his office been able to complete the review, he would have recommended the RCMP compensate the complainant to recognize that, but for the actions of the RCMP, the complainant would have been awarded the contract.

Follow-ups

In addition to launching 4 formal reviews, we also undertook a follow-up exercise with 4 federal departments that were the subject of reviews in previous years.

In March 2020, the Procurement Ombudsman sent letters to the 4 federal departments to inquire if the recommendations made during previous reviews were followed. The reviews in question included recommendations for the payment of compensation of 10% of the total value of the contract to the complainant. We received responses from 3 of the 4 deputy heads of these departments indicating that compensation had indeed been paid to the supplier. We expect to receive a response from the final department in early 2020-21.

We review procurement practices

In addition to reviewing complaints about the award or administration of specific contracts, we also review the procurement practices of federal departments for the acquisition of goods and services to assess their fairness, openness and transparency.

As noted in our 2018-19 Annual Report, the Procurement Ombudsman approved a five-year plan for undertaking procurement practice reviews. The Procurement Practice Review Plan (2018-23) is an important way to ensure we focus our efforts and resources on the highest risk areas within the procurement process. In establishing our procurement practice review priorities, we conducted environmental scans, literature reviews, data analyses, assessment of key risks to fairness, openness and transparency, and assurance mapping of all procurement-related audit and review work conducted in federal organizations.

We also examined other sources, including:

- Issues raised by the supplier and the federal procurement communities, as highlighted in our “Top 10” list of issues

- Issues identified by professional and industry associations

- Issues identified in federal organization internal and external audits

In line with the multi-year plan, we completed 2 reviews launched in 2018-19, and launched 2 more in 2019-20. We performed these reviews to determine whether federal departments’ procurement practices pertaining to the following lines of enquiry supported the principles of fairness, openness and transparency: (i) evaluation criteria and selection plans; (ii) solicitation documents; and (iii) evaluation of bids and contract award. We assessed these lines of enquiry for consistency with Canada’s obligations under applicable sections of national and international trade agreements, the Financial Administration Act and regulations made under it, the Treasury Board Contracting Policy and departmental guidelines. What follows are summaries of the 2 completed reviews.

Procurement practice review of the Canadian Food Inspection Agency

The Procurement Ombudsman made 8 recommendations to the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA). The Ombudsman recommended the CFIA should:

- Ensure that evaluation criteria are limited to the performance elements necessary to the success of the project and do not favour a particular supplier; that weighting schemes do not disproportionately skew evaluation results; and that minimum thresholds for point-rated criteria are reasonable.

- Implement measures to ensure mandatory criteria are clear, precise and measurable, and adequately defined to support the preparation of responsive bids and the evaluation of proposals.

- Ensure that procurement policies are reviewed regularly, kept up-to-date, and contain sufficient detail to clarify roles, responsibilities and procedures for awarding contracts.

- Establish appropriate review mechanisms to ensure that information shared with suppliers is accurate and complete.

- Implement an effective mechanism to ensure that procurement files pertaining to call-ups issued against standing offers are sufficiently documented to facilitate management oversight and establish a clear audit trail.

- Develop appropriate review mechanisms to ensure that procurement strategies do not unnecessarily divide aggregate requirements and circumvent approval authorities.

- Establish a mechanism to ensure bid evaluations are consistent with properly designed and disclosed evaluation procedures, and are appropriately documented.

- Implement an effective mechanism to enforce the requirement to maintain up-to-date and complete procurement files.

Read the full report: Procurement practice review of the Canadian Food Inspection Agency.

We will conduct a follow-up review in 2 years to assess the implementation of the CFIA’s action plan to address our recommendations.

Procurement practice review of the Department of Fisheries and Oceans

The Procurement Ombudsman made 6 recommendations to the Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO). The Ombudsman recommended the DFO should:

- Ensure all procurement records are retained, organized and accessible for the period of time required by Treasury Board record-keeping standards.

- Ensure evaluation criteria are reviewed to eliminate bias and ensure clarity prior to publication.

- Ensure clarity and consistency in its solicitation documents to avoid discrepancies and ensure transparency in its bidding processes.

- Properly document its files to demonstrate how its contracting personnel are giving all qualified firms an equal opportunity for access to government business, and how its contracting personnel are decreasing any possible bias or incumbent advantage.

- Ensure that a standard “evaluation package” including a Confidentiality form and Conflict of Interest form are signed by all evaluators and recorded on file prior to providing evaluators access to bids.

- Put a mechanism in place to ensure evaluation processes are adhered to and contracts are awarded to the appropriate, qualified bidder.

It is important to note the DFO was unable to produce documentation in a timely manner about how 6 of the 40 contracts subject to review were awarded. The lack of documentation means the DFO is unable to refute any challenges from bidders and reviewers/auditors as to how its procurements met its fairness, openness and transparency obligations.

Read the full report: Procurement practice review of the Department of Fisheries and Oceans.

We will conduct a follow-up review in 2 years to assess the implementation of the DFO’s action plan to address our recommendations.

Reviews to be completed in 2020-21

When the Procurement Ombudsman launches a procurement practice review, he must provide his recommendations within 1 year of the commencement of the review. The Procurement Ombudsman launched a review of Environment and Climate Change Canada in July 2019 and also launched a review of Employment and Social Development Canada in October 2019. As a result of their timing, these 2 reviews will be completed by July 2020 and October 2020, respectively, and reported on in our next annual report.

In line with the multi-year plan referenced above, the Procurement Ombudsman also intended to launch 2 additional reviews in March 2020 that were subsequently delayed as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. These reviews will instead be launched in 2020-21 and completed within legislative timeline completed within legislative timelines.

11. A word on our commitment to you

However you choose to interact with our office, our goal is always the same—we want to help you. If the issue you are facing does not fall within our mandate, we will still do our best to point you in the right direction.

We will listen to you. We will connect you to the right people. We will work to help you resolve the problem.

That is our commitment to you.

Appendix A

Statement of operations for the year ended March 31, 2020

1. Authority and objective

The position of Procurement Ombudsman was established through amendments to the Department of Public Works and Government Services Act. The Procurement Ombudsman’s mandate is further defined in the Procurement Ombudsman Regulations. The Office of the Procurement Ombudsman’s mission is to promote fairness, openness and transparency in federal procurement.

2. Parliamentary authority

The funding approved by Treasury Board for the operation of the Office of the Procurement Ombudsman is part of Public Works and Government Services Canada’s (PWGSC)Footnote 9 appropriation, and consequently, the Office is subject to the legislative, regulatory and policy frameworks that govern PWGSC. Nonetheless, implicit in the nature and purpose of the Office is the need for the Office of the Procurement Ombudsman to fulfill its mandate in an independent fashion, and be seen to do so, by maintaining an arm’s-length relationship with PWGSC.

3. Statement of operations

| Expenses | 2019-20 ($000) |

|---|---|

| Salaries and employee benefits | 2,834 |

| Professional services | 209 |

| Operating expenses | 114 |

| Information and communication | 156 |

| Materials and supplies | 32 |

| Corporate services provided by Public Services and Procurement CanadaFootnote 10 (finance, human resources, information technology, office relocation, other) | 636 |

| Total | 3,981 |

4. Proactive disclosure

Compliance with the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat and Public Services and Procurement Canada (PSPC) financial management policies requires the mandatory publication of the Procurement Ombudsman’s travel and hospitality expenses. It also requires disclosure of contracts entered into by the Office of the Procurement Ombudsman for amounts over $10,000. Information on our proactive disclosures can be found by selecting the “Disclosure of Travel and Hospitality Expenses” link on PSPC’s “Transparency” webpage or on the “Open Canada” website by searching for “Procurement Ombudsman.” Disclosure of our contracts are published under PSPC as the organization.

- Date modified: